Jerry Manock is one of the great unsung heroes of Apple design. As the father of Apple’s Industrial Design Group, Manock made an indelible contribution to the company’s long line of hit products.

He may not be a household name like Jony Ive, but, starting with the Apple II, Manock played a massive role in making the company what it is today. In an exclusive interview with Cult of Mac, the 76-year-old industrial designer recounts many colorful stories about Cupertino’s past — including one that shows even Steve Jobs got nostalgic.

Manock was Apple’s first proper industrial designer. He designed the case for several iconic Apple computers, including the Apple II and the original Macintosh. A graduate of Stanford University, Manock had just launched his career as a freelance industrial designer when, in 1977, he got a call from Steve Jobs, co-founder of a new startup.

“It wasn’t a case of thinking, ‘What am I getting into with Apple?'” Manock told Cult of Mac. “It was more like this was another electronic project design I could do really easily.”

At the time, he could never have imagined how significant a part of his life Apple would become.

How Jerry Manock hitched his wagon to the Cupertino star

Jobs wanted Manock, then in his early 30s, to build a case for the Apple II.

Although personal computers were still geeky tools for hobbyists, Jobs wanted something that looked beautifully machined, as if it had rolled off a conveyor belt at some high-end factory. He also wanted it in just two months.

Others had already turned down the job. Manock took it. He quoted Jobs $1,800 — and even offered him a discount if Apple paid him within 10 days.

In the end, Jobs didn’t pay on time but, when he did pay, Manock saw that he had paid only the discount price, with an additional fraction of that cost added for every day Jobs had overran on payment. It was a sneaky move, although entirely in keeping with Jobs at the time.

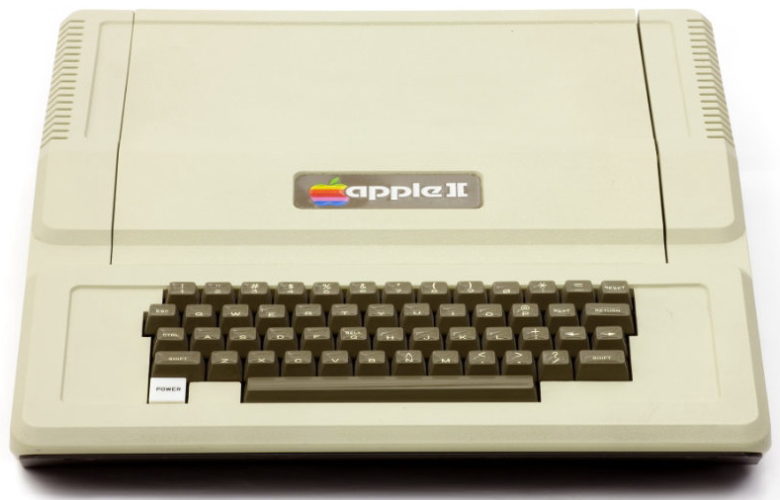

Apple II: Manock designs a winner for Apple

Photo: Computer History Museum

The Apple II became a powerhouse hit for Apple. Manock laughed as he recalled trying to retroactively negotiate a royalty rate of $1 for every Apple II sold following the computer’s massive success.

“I mean, how stupid can you get to try to negotiate a royalty agreement after the fact?” he said. “I can’t imagine how dumb that sounded to [Steve]. We were walking back from a restaurant after lunch. He didn’t even break his stride. He said to me, ‘If you knew how many Apple IIs we’re going to sell next year, you’d know that I can’t do that. You’re good. But you’re not that good.”

Manock was offered a job as Apple’s fifth employee. However, he insisted that he stick to working as a freelancer on an hourly rate. When Apple went public in December 1980, Manock said the person who actually became the company’s fifth employee was worth $75 million overnight.

“Oh my goodness,” Manock said. “I’ve had some people ask me if I’m upset about that. But Apple treated me really well. I don’t have any regrets at all about what I did and what could have been. They were very generous in giving bonuses out for work that Jobs considered good work. They treated me well.”

Jerry Manock’s Apple designs: Hits and misses

Photo: Alker33/YouTube

The notorious Apple III

Not every Apple computer Manock designed became a massive hit. After the Apple II, he worked on the notorious flop known as the Apple III. Although he remains happy with the appearance of the computer — which looks like a continuation of the Apple II design language — the machine proved prone to failures. This lack of reliability ultimately ruined user confidence in the Apple III.

“The Apple III was introduced at a computer conference in Anaheim, California,” Manock said. “For the introduction, Jobs wanted to put on a free night for 25,000 off his best friends at [the nearby] Disneyland. They closed Disneyland, kicked everybody out. You had to have a special Apple pass to get in. I guess that was something where they said, ‘Well, we just can’t change that. We can’t cancel it. We’re not going to, you know, say the computer isn’t ready and still has some problems.’ They just went ahead and introduced it because they had this fantastic event for everybody. And that was obviously a mistake in hindsight.”

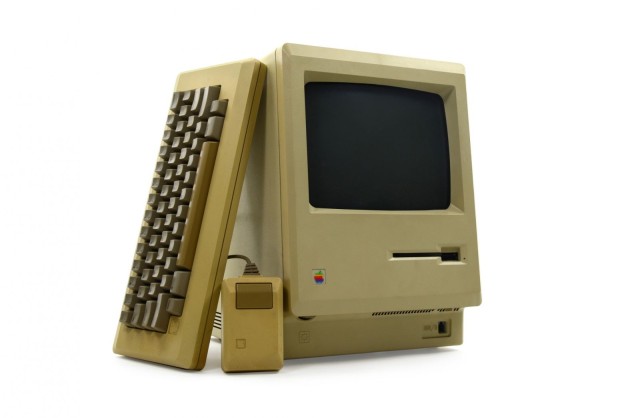

The magnificent Macintosh

By the early 1980s, Manock officially joined Apple as corporate manager of product design. He went on to work on a project called the Macintosh, one of history’s most famous personal computers. (He’s one of the creators who had their names inscribed on the first Macs because, as Steve Jobs said, real artists sign their work.)

“I don’t hesitate at all in saying that the Macintosh was the greatest pleasure,” Manock said. “They had money to spend on design. Steve never questioned spending whatever it would take to get the excellence in design that he wanted. I didn’t have to beg for money to do the tooling and be able to make prototypes and models. It was overall incredible acceptance, and very, very gratifying.”

The Mac is the design Manock is most proud of at Apple. It’s instantly recognizable — friendly and approachable, but also iconic in its shape. It’s the Volkswagen bug of computers.

Like a lot of the Macintosh team, Manock left Apple after the first Mac shipped. He felt burned out. He moved with his wife and kids to Burlington, Vermont — about as far away from the madcap bustle of Silicon Valley as you could hope for. Originally, they planned to stay for six months. They still live in Burlington today, and Manock still runs his own design company there.

The last time Jerry Manock saw Steve Jobs

Manock exchanged the occasional email with Jobs, about three per year. On one occasion, he suggested Jobs fly into Burlington on one of his trips from California to New York.

“At that time, he was recognized wherever he went,” Manock said. “He’d get surrounded by this mob of people. I said that you could walk down Church Street and, while people might recognize you, they wouldn’t bother you.” But Jobs declined the offer and said he’d rather spend time with his family.

Photo: iFixit

Then, in the mid-2000s, Manock came to San Francisco. He had held onto around 35 Apple shares over the years, and decided to go to one of the annual shareholders meetings with his wife. Manock didn’t bother Jobs by telling him he would be in town. He and his wife went to the meeting and sat in the fourth or fifth row.

“When Steve came out, I saw him kind of scanning the audience, and he saw me there,” Manock said. “He gave my wife and I this little three-finger wave, just a very, very subtle acknowledgement that we were there. I thought that was kind of neat.”

Then, as the meeting wrapped up, something happened that Manock said “just totally blew my mind.” Jobs addressed the shareholders and said, “Before we break up for today, I just want to acknowledge two people in the audience.” He then motioned to Manock and his wife sitting in the audience.

Telling the story, Manock choked up. “Oh, geez, I’m getting teary just talking about it,” he said. “He mentioned, you know, my contribution to the Apple II, Apple III and the Macintosh. And I got a standing ovation.”

It was the last time Manock ever saw Jobs.

Paying homage to Apple’s past?

Photo: Bill Jason

Contrary to what you might expect, Manock said he doesn’t receive much in the way of correspondence from Apple. If there’s a list of former employees who get sent the latest gadgets, Apple’s first industrial designer is not on it.

“I’ve been waiting for them to send one of those $55,000 Mac Pros,” he laughed. But it also makes him a bit sad. “Apple has a pretty long history of totally ignoring their past,” he said. “Which is very, very sad — but so it is.”

Jony Ive misses a meeting

Several years ago, Manock and some other early Apple employees arranged to visit Apple and Jony Ive, the company’s longtime guru of industrial design. (Ive retired from Apple in 2019 to go solo.)

The day before their visit, Manock’s group received an email from Ive’s executive assistant saying that their meeting had been scrubbed. “There was no reason or anything, just [a message] that our meeting is canceled,” Manock said.

Despite being the oldest and most storied of the current tech giants, Apple doesn’t exactly pay homage to its past. There’s the odd shot of a vintage PowerBook at an Apple keynote, but for the most part Cupertino doesn’t do much to celebrate its history. But, whether it wants to or not, there’s a design through line that runs from the very first Apple II computers through the Mac all the way to the latest iPhones.

“I don’t think there’s a specific design detail [that’s mine], but when I look at my iPhone in front of me, it sort of invites interaction,” Manock said. “That’s something I always tried to do. It’s one of those general design guidelines that I think have been carried over.”

A selection of Jerry Manock’s Apple memorabilia is part of RR Auction’s current Steve Jobs auction.