Why couldn’t you type the F-word on the iPhone? Why did Steve Jobs make weird eye movements during demos? What kind of manager was Scott Forstall?

These and other questions are answered in a new book by Ken Kocienda, a former iPhone programmer who spent 15 years at Apple helping to develop the first iPhone, iPad and Safari web browser.

Published this week, Creative Selection, Inside Apple’s Design Process During the Golden Age of Steve Jobs, is a fascinating account of Kocienda’s career that focuses on how Apple makes great software. (read our review here)

Here are some of the most interesting things we learned from the book.

This post contains affiliate links. Cult of Mac may earn a commission when you use our links to buy items.

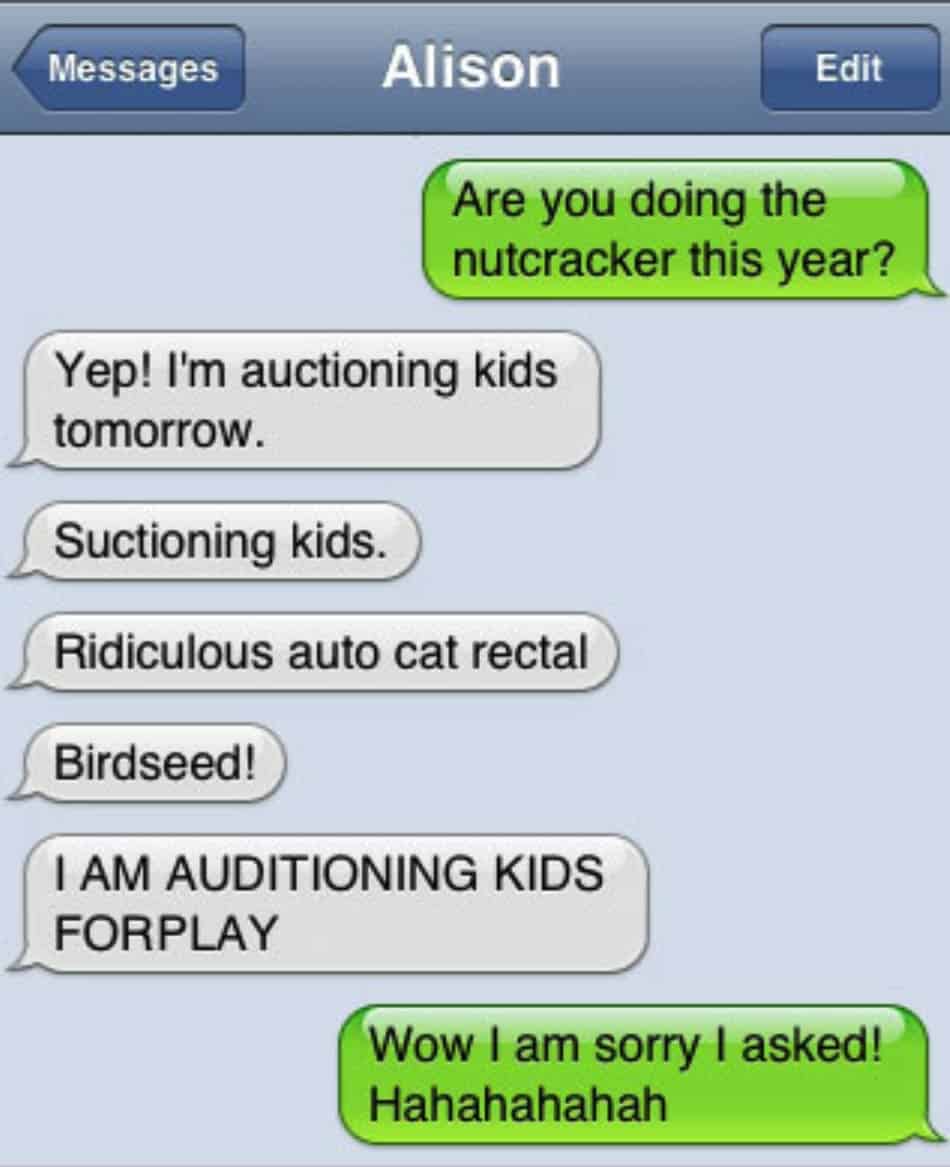

Why you can’t type the F-word on iPhone

Photo: autocorrectfailness.com

When it launched, the iPhone gained notoriety for replacing the F-word with the D-word (duck). Some thought it was prudery on the part of Apple, but there’s a good reason you couldn’t type swear words. It was all because of autocorrect. As Kocienda details in Creative Selection, autocorrect was the secret sauce that made the iPhone’s tiny keyboard actually useable. Without it, the keyboard was unusable. But when developing it, Kocienda discovered that autocorrect would often insert swear words and hate speech. He was horrified. The last thing he wanted was a string of filthy words showing up onscreen accidentally, so he built a dictionary of verboten words that would never be inserted by autocorrect — whether you meant to type them or not. And that’s why you get ‘duck’ when you meant ‘*uck.’

Why the clock is always set to 9:41 in Apple keynotes

Photo: Apple

There’s a reason the clock is always set to 9.41 in Apple’s keynotes. That’s because the big reveal was usually timed for 40 minutes into the keynote, and Steve Jobs wanted the product to show the actual time. The one exception is Apple Watch demos. Apple’s industrial design team prefered the hands of the watch to be at 10.09, particularly on analog watch faces. It’s more aesthetically appealing.

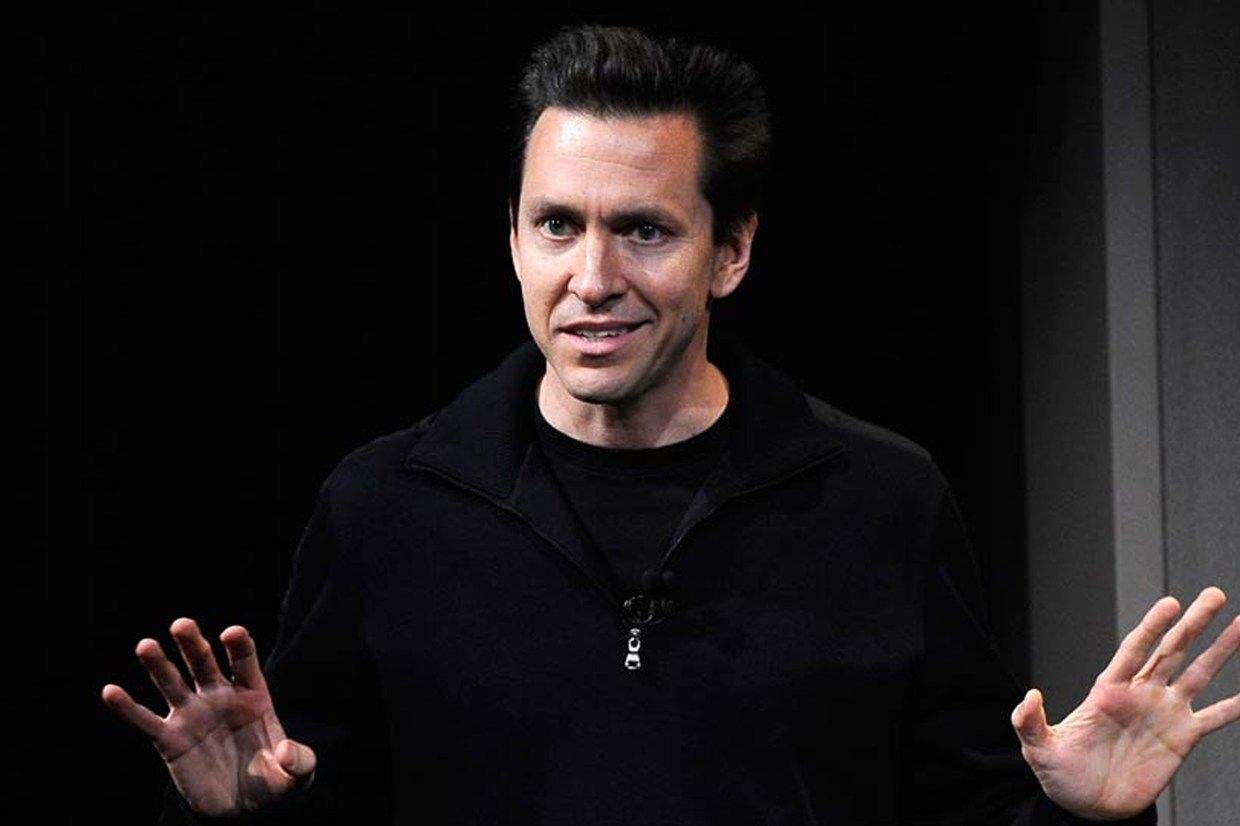

Scott Forstall sounds like a really good manager

Photo: paz.ca/ Flickr CC

Scott Forstall was once the biggest rising star at Apple. The former head of iOS development, Forstall was frequently tipped as a potential CEO candidate. But he was canned by Tim Cook in 2012, supposedly for bungling Apple Maps and refusing to apologize for it. The firing tarnished Forstall’s reputation. He’s been labelled as a bit of a prima donna, ‘political,’ and a careerist backstabber. But in Kocienda’s book, Forstall comes across as a great manager. In the book, it’s clear that Forstall was good at building and leading the team that developed the iPhone’s software. He appears thoughtful, caring and good with people. He often has kind words to say to his team, and protects them from the higher ups (IE. Steve Jobs). I was surprised. The book really bolsters Forstall’s reputation.

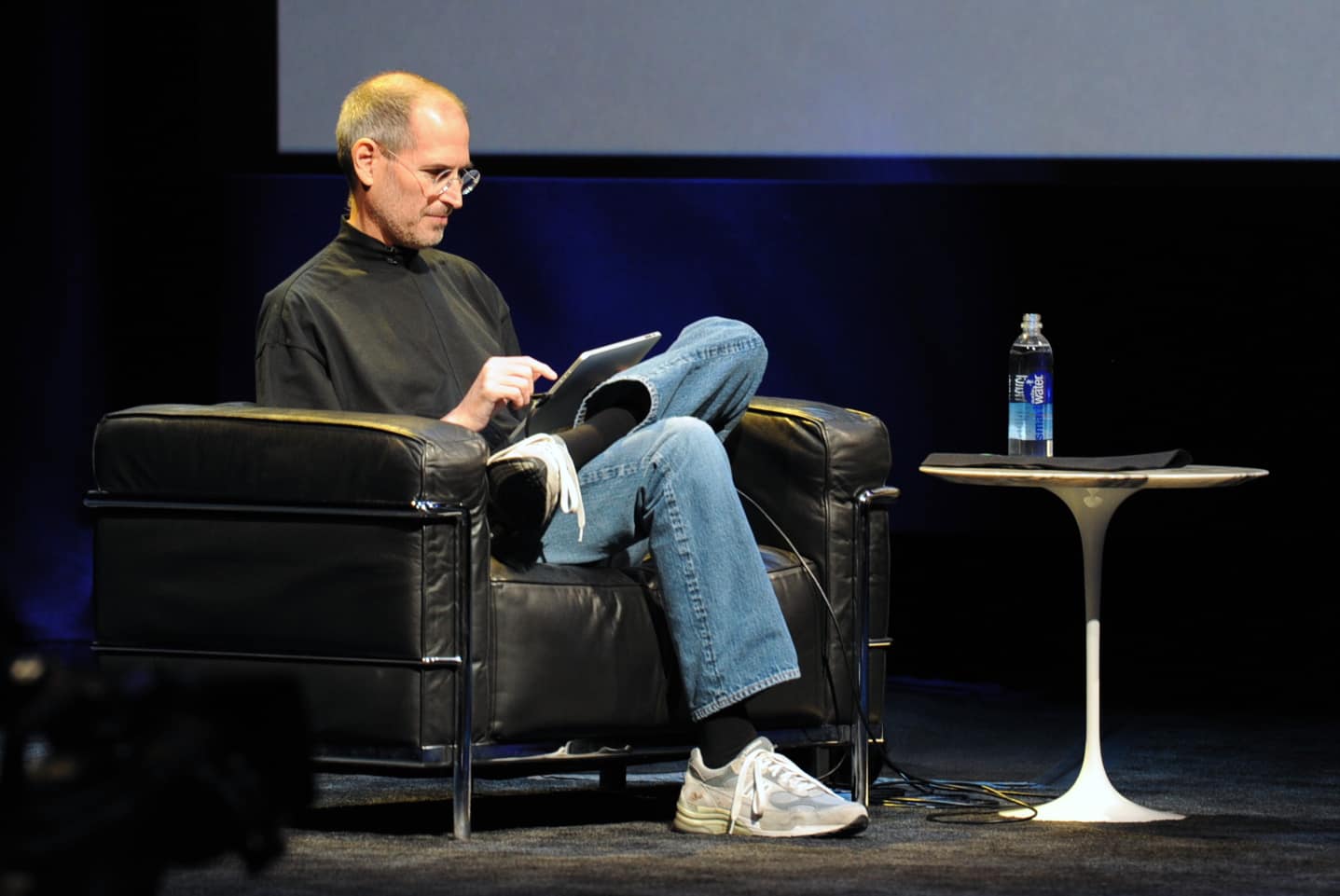

Steve Jobs made weird eye movements during software demos

When shown something new during a software demo, Steve Jobs rotated his head and eyes though small figure-eight movements. It looked odd, but he did it deliberately so that he could look at the screen through his peripheral vision as well as straight on. The movements allowed Jobs to examine something new from a lot of different angles, to see if it looked as good with a sideways glance as looking at it directly.

Steve Jobs prepared for his keynotes for weeks

Photo: Apple

Jobs always seemed loose and natural durning his keynotes, but every word was very carefully rehearsed, revised and rehashed for many weeks. Jobs’ preparation began months in advance. As the keynote drew near, he rehearsed daily at the Town Hall theater at Apple HQ in front of an audience of executives and trusted lieutenants. He constantly revised his speech until he felt it was perfect. The weekend before, Jobs went through two full dress rehearsals on both Saturday and Sunday. Absolutely nothing was left to chance.

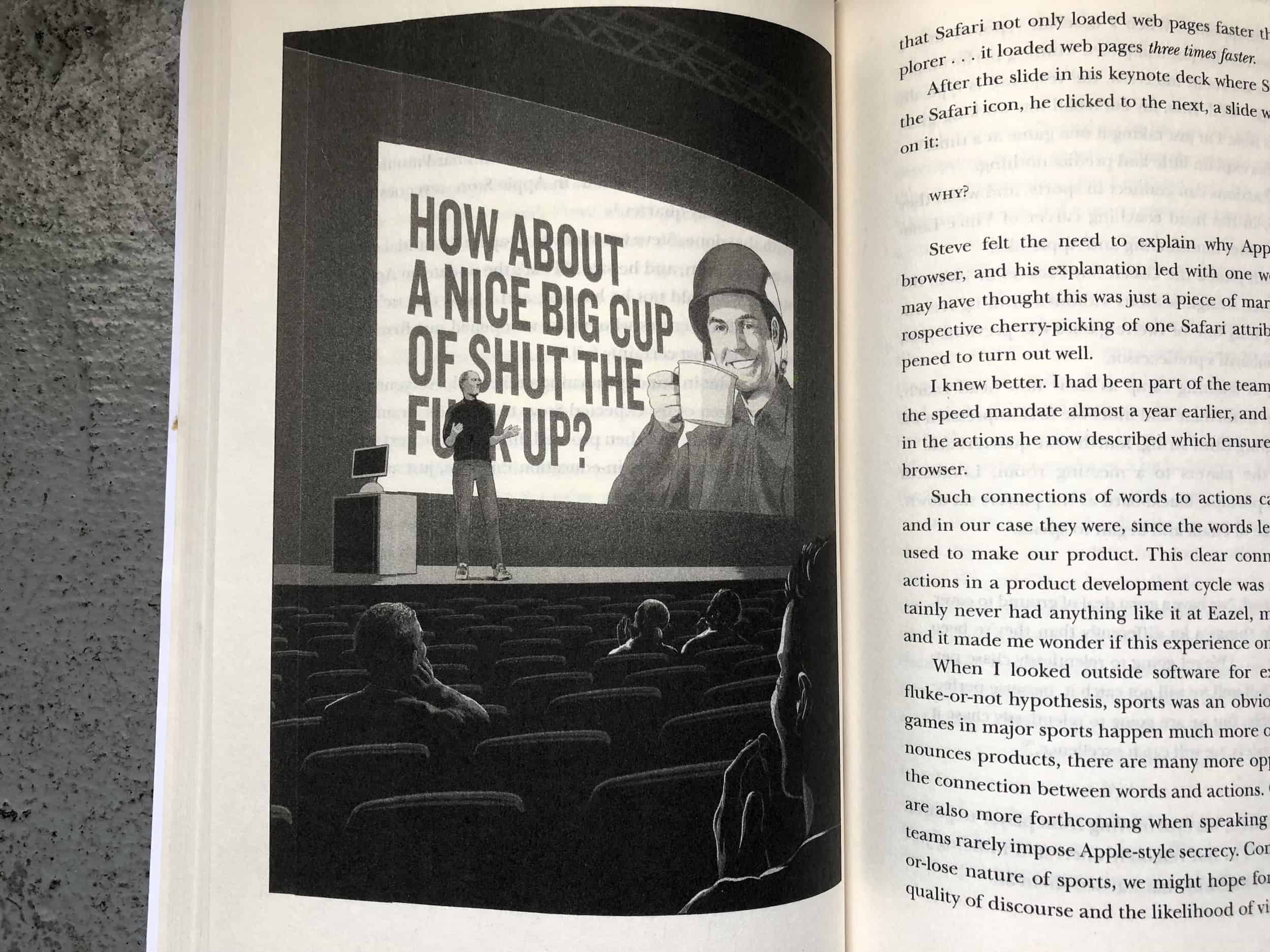

During a keynote rehearsal, Jobs made a blue joke about Apple critics

Photo: Guy Shield/Ken Kocienda

During one keynote rehearsal, which Kocienda witnessed, Jobs gave an update about Apple’s retail stores, which had opened not long before. Jobs noted that critics predicted the stores would fail. He then flashed a surprise slide on screen that the rehearsal audience hadn’t seen before. They got a good laugh out of it, but alas it wasn’t included in the real thing.

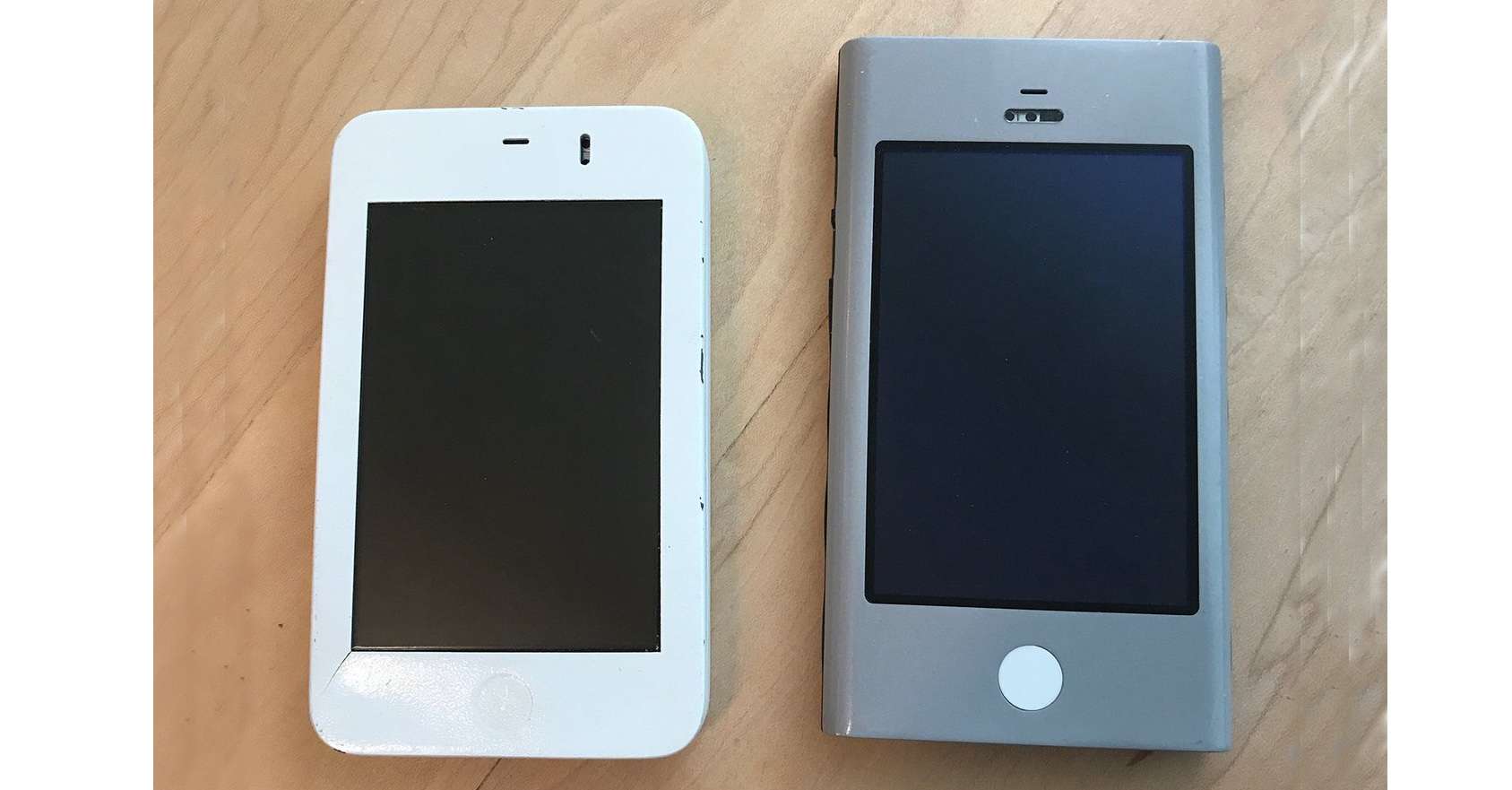

These are the ‘Wallabies’ used to develop the iPhone’s software

Photo: Ken Kocienda

Kocienda talks a lot about these ‘Wallabies’ that were used to test the software developed to run the iPhone. They had plastic screens but no electronic guts. They were tethered to a Mac that provided the processing power.

Upon seeing a rough prototype, Kocienda immediately wanted an iPhone

Photo: Jim Abeles

Because of Apple’s super tight security, Kocienda didn’t see the hardware at all until the last minute. A few weeks before launch, a manager brought in a working prototype to show the software team. It wasn’t sealed properly because it was using internal components. They hadn’t been finalized yet and were too big to fit properly into the case. Despite it bulging at the seams, Kocienda instantly wanted one — as did the rest of the world when it launched.

Demos are at the heart of Apple’s creative process

Photo: Pexels

Apple’s creative process is built around demos. Programmers would constantly demo their work to colleagues and managers, garnering feedback that would make the next demo better. The process made vague ideas concrete, ensured bad ideas got weeded out and good ideas flourished. The process, Kocienda says, is Darwinian: good ideas are ‘selected,’ hence the name of his book: Creative Selection.

Not all programmers are math geniuses

I used to think that being good at math was a prerequisite to being a programmer, but Kocienda reveals that he’s not good at math. When he asked for help and colleagues bombarded him with math, he said it was ‘over his head’ and he found different, non-mathematical solutions instead.

Steve Jobs used a NeXT Cube for years because of email

Photo: Wikipedia CC

For years after Jobs returned to Apple in the late 19990s, he used a computer from his previous company NeXT. According to Kocienda, Jobs was ‘fixated’ on email and wasn’t a fan of the way the Mac handled email. He preferred the email client on the NeXTcube. Years later, Jobs would order the development of the iPad so that he could read his email on the toilet.

iPhone’s keystroke is the sound of a pencil strike

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The sound of the iPhone’s keyboard was made by striking a pencil against a tabletop. Kocienda was inspired by the story that the blaster sounds in Star Wars were created by striking a hammer against a utility pole tension wire.

Size of iPhone’s icons were determined by a game

Photo: Leander Kahney/Cult of Mac

When developing the iPhone, it wasn’t clear how big the app icons on the Home screen should be. The size of icons was determined by a simple game. One of the programmers, Scott Herz, made a game that put different size boxes (which represented the icons) in different parts of the screen at random. The idea was to hit the square and then another randomly generated square appeared. The game was surprisingly fun and the whole team played it for a week on their Wallabies. Behind the scenes, the program determined that no matter where on the screen it appeared, a square the size of 57-pixels-square could be hit every time, and thus that’s how big icons should be.

Legendary Mac programmer Bill Atkinson made a wooden iPhone

Photo: Jim Merithew/Cult of Mac

Programmer Bill Atkinson is a god in the Apple world. Atkinson designed much of the original Mac graphical user interface, as well as early apps like MacPaint and HyperCard. But when the iPhone was lauched in 2007, he had long left Apple. He had to line up outside the store like everyone else. Kocienda ran into him on the morning of the launch outside the Palo Alto store, and was surprised to see he was carrying something that looked very much like an iPhone. It turned out to be a wooden model that Atkinson had made. He was so excited about the iPhone, he made his own wooden mockup to carry around. Kocienda was delighted.