This feature is adapted from my book, Jony Ive: The Genius Behind Apple’s Greatest Products. It offers a rare look inside one of Apple’s most secretive institutions: the Industrial Design studio.

Where do Apple’s great products come from?

For the last 18 years — since Steve Jobs returned to the company in 1997 — most of them have come out of Apple’s Industrial Design studio, a small and secretive group of creatives headed up by celebrated British designer Sir Jony Ive.

Ive and his group of industrial designers are the principal inventors at Apple. They conceive and create new products, refine existing ones, and do some fundamental research and development, though they are not the only R&D group within the company. They investigate new materials and production processes. They constantly refine and improve Apple’s products and manufacturing techniques.

Apple designer Christopher Stringer defines the role of an industrial designer at Apple as one “to imagine objects that don’t exist and to guide the process that brings them to life. And so that includes defining the experience that a customer has when they touch and feel our products. It’s managing the overall form and the materials, the textures, the colors. And it’s also working with engineering groups to, as I say, bring it to life, to bring it to the market and to build the craftsmanship that it absolutely needs to have to have that Apple quality.”

Ive’s Industrial Design group is small, about 20 designers from around the world. They are extremely tight-knit, especially because many of them have worked at Apple for decades. By comparison, Samsung has 1,000 designers working in 34 research centers around the world. Of course, Samsung makes many more products than Apple (and even builds some components of the iPhone and iPad).

Here’s a rare look inside the super-secretive world of the Apple Industrial Design group.

Inside the Apple Industrial Design group’s studio

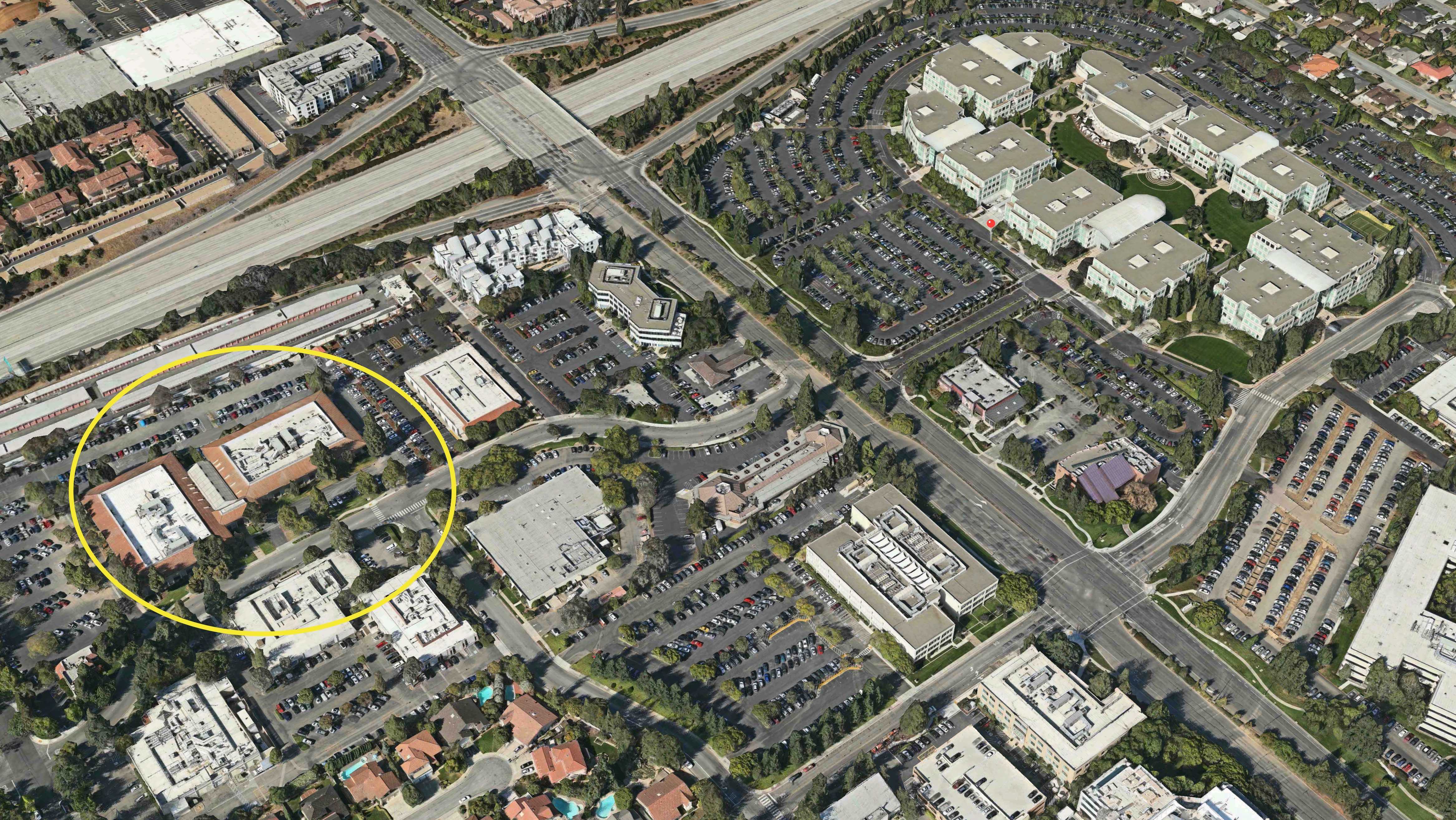

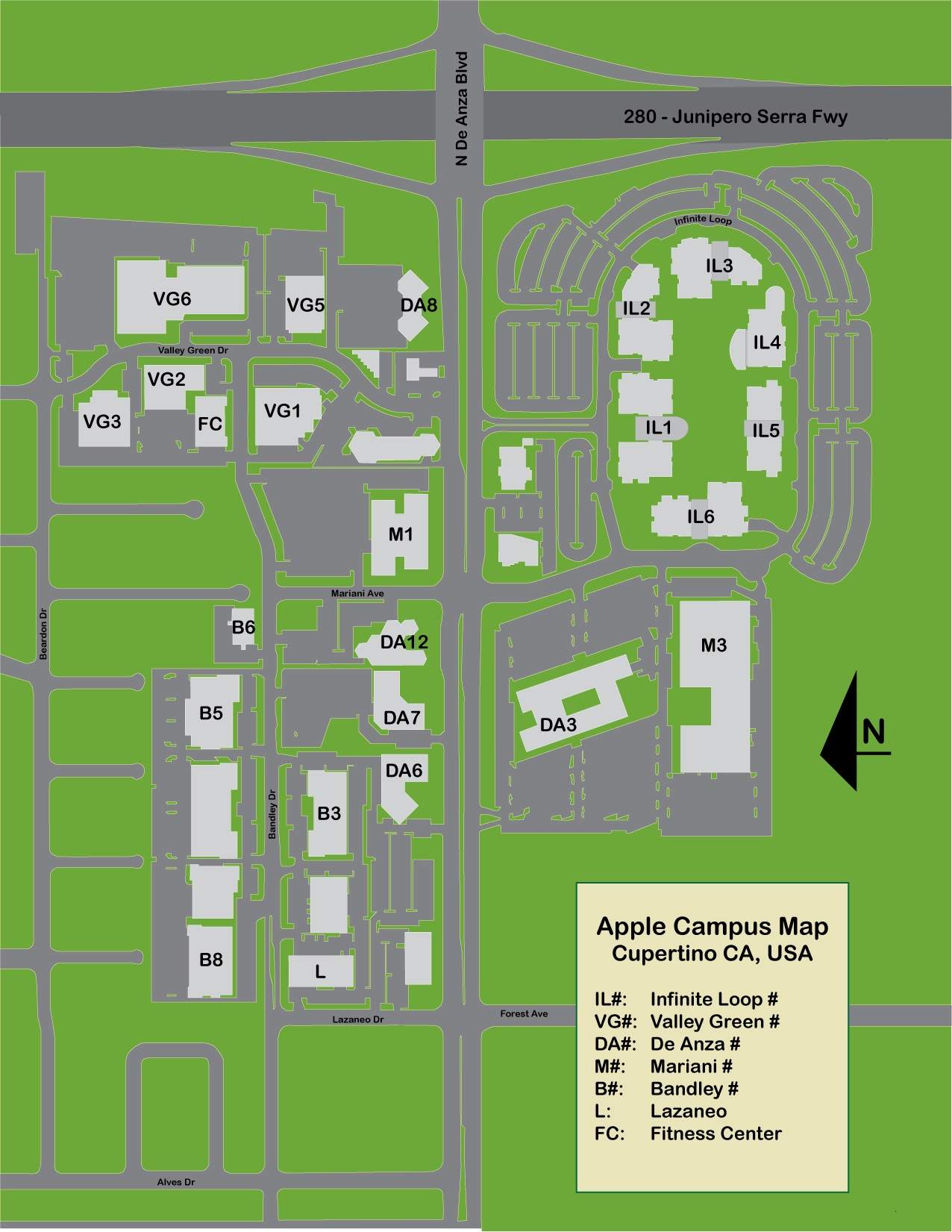

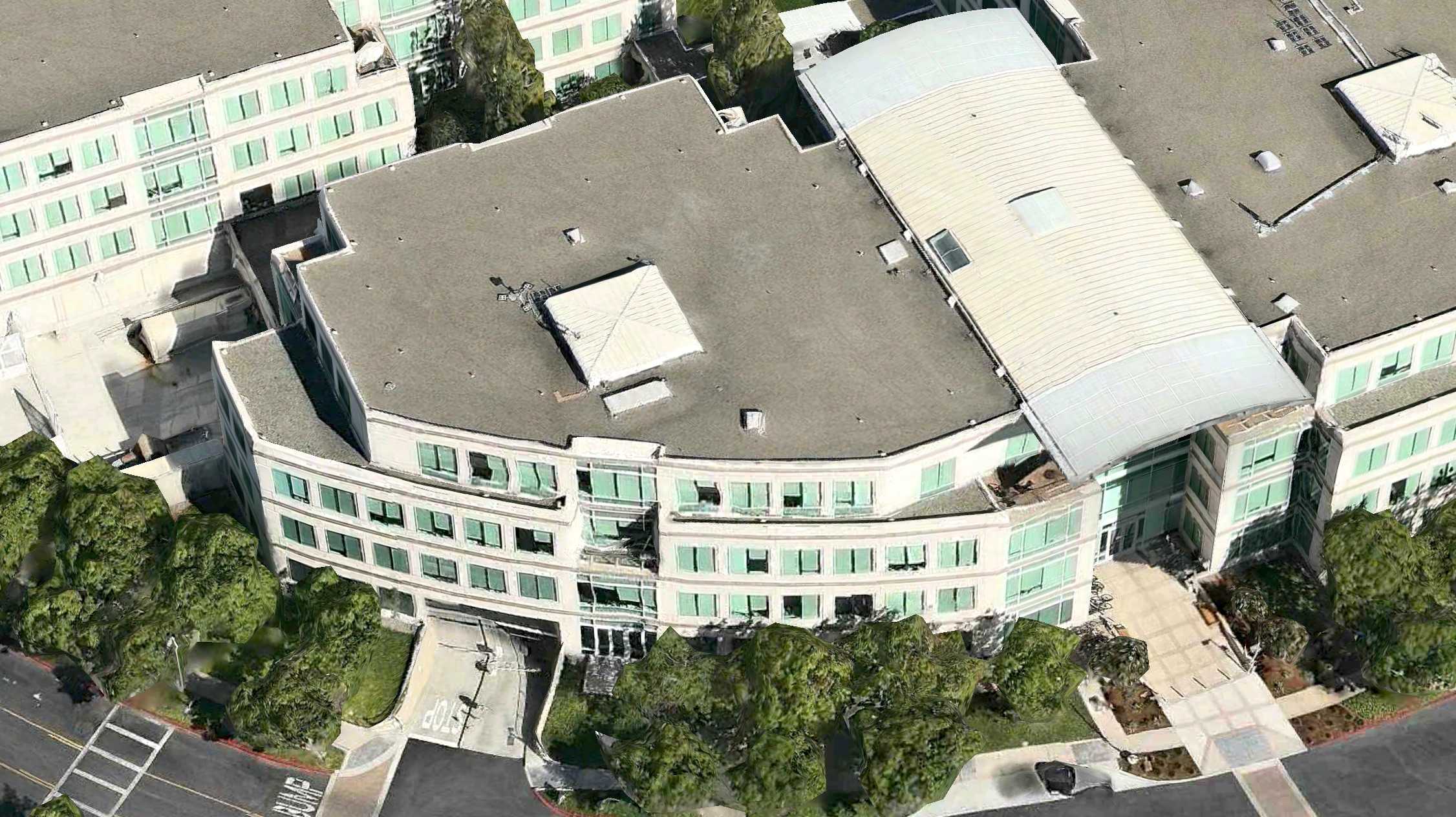

On February 9, 2001, after the hubbub of Macworld died down, Apple’s Industrial Design studio moved from the building on Valley Green Drive (across the road from Apple’s main campus) to a large space inside Apple’s HQ. The new design studio was put on the ground floor of Infinite Loop 2, known internally at Apple as IL2.

It was a big, symbolic move. The founder of the ID group, designer Bob Brunner (now at Ammunition), had set up the original studio across the street to give it some independence from the rest of the company. Now Jony Ive and his team were being moved back into the heart of Apple, allowing CEO Steve Jobs to work more closely with them. It cemented the elevated status of design within the company. In Jony’s words: ID was now truly “close to the heartbeat of the company.”

It was a big move logistically, too. The studio is home to a lot of large machinery, including prototyping equipment. In addition, everything in the new studio was purpose-built. “Every single thing in that space was custom-made,” said former Apple designer Doug Satzger. “Every piece of furniture, all the tables, the chairs, every piece of glass.”

The studio is a large space, occupying most of the ground floor of IL2. It’s recognizable from the outside only by the wall of large, frosted-glass windows across the bottom of the building. The opaque windows prevent anyone from getting a peek inside. Security is extremely tight.

The studio is divided into several different spaces. To the left of the entrance is a well-equipped kitchen with a large table. This is the heart of the studio where Ive’s team conducts its biweekly brainstorming sessions. To the right of the studio’s front entrance is a small conference room that is rarely used.

Jony Ive’s glass-walled office

Opposite the front entrance is Ive’s office. It’s a glass cube, and the only private office in the studio. It measures about 12 feet by 12 feet. The front wall and door are made of glass with stainless steel fittings, just like the ones in Apple’s stores. Except for a small shelf system, his office is bare, with plain white walls. There are no pictures of his family or design awards, only a desk, chair and lamp. The desk was custom-made by Marc Newsom, one of Ive’s best friends and now a member of the Industrial Design team. (Newsom was hired in September 2014.)

Ive’s leather chair is a Supporto chair from U.K. office furniture manufacturer Hille International. Designed in 1979 by award-winning designer Fred Scott, the leather-and-aluminum chair is recognized as a design masterpiece. Ive has named it one of his favorite designs, and selected it for the new Industrial Design Centre in Cupertino, California. “The Supporto is a wonderful chair,” he told ICON magazine. The studio is filled with them: The designers all sit at Supporto desks and leather chairs.

Ive’s desk is usually bare except for his 17-inch MacBook and several colored pencils for drawing, which are typically arranged neatly on his desk. He doesn’t use an external monitor or any other peripheral equipment.

The presentation tables

Directly outside Ive’s office are four large, wooden project tables, which are used to present prototype products to executives. This was where Steve Jobs gravitated when he visited the studio, which became almost daily. In fact, this is where Jobs got the idea for the big, open tables in the Apple stores.

In the studio, each table is dedicated to a different project — one for MacBooks, another for the iPad, the iPhone and so on. They are used to display models and prototypes of whatever Ive wants to Apple executives. The models are covered at all times with black cloth.

The CAD room and the ‘shop’

Next to Ive’s office and the presentation tables is a large computer-assisted design (CAD) room. It’s another glass cube, also fronted by a glass wall. The CAD room is home to about 15 CAD operators or “surface guys.” If the designers want to see what a CAD model looks like as a real object, they’ll send the file to the computer numerical control (CNC) model shop next door. Sometimes they output “scrap models,” which might be a detail, like the corner of a product or a button.

At the far end of the space is a machine room, or “the shop.” The shop is also fronted by a glass wall. It is divided internally into three rooms separated by more glass walls. To the front are three big CNC machines. These are hulking milling machines, capable of crafting anything from metal to RenShape foam board.

Their covers keep any scrap material contained, so they are “clean.” Behind them are the “dirty” machines — various cutting and drilling machines that can create a mess. They are housed in a room sealed behind glass — the “dirty shop.” Next to the dirty shop and to the right is a finishing room where the models and prototypes get sanded and painted. It contains some fine sanding machines and a big paint-spraying booth about the size of a car.

The shop is used by the design team to make models of upcoming products. The CNC machines are used to make initial models or to quickly validate ideas. “They’d get a CAD file for surfacing; they would create a tool path based on the surfaces, do all the setups, and run a part,” said Satzger. Oftentimes, Ive’s team makes hundreds of models, just like he did in college. As the product-development process progresses, the design team will outsource model-making to an outside specialist firm.

The designer’s workspace

Jony Ive’s office, the presentation tables, the CAD room and shop are all to the right of the front entrance. To the left, there’s an opening by Ive’s office that leads to the space where the designers work. It’s a large, open space lined by the long wall of exterior frosted windows.

The designers work on five large tables, subdivided by low dividers. The space is messy and chaotic. There are boxes, parts, samples, bikes and toys everywhere. The atmosphere is light and fun. “Someone might be skateboarding in there, doing jumps, or Bart Andre and Chris Stringer kicking a soccer ball,” said Satzger.

The atmosphere in the Apple Industrial Design studio

Music is an important part of the design studio’s fun atmosphere. There are about 20 white speakers in the room, with a pair of 36-inch-high concert subwoofers. “When you walked into this concrete-and-steel, highly reflective room, the sound was immediately deep and loud,” Satzger said. “All kinds of music from around the world is played. It’s really lively.”

Ive is a big fan of techno. The music drove his former boss, Jon Rubinstein, to distraction. “They played loud techno-pop in the design studio, which I found really annoying,” he said. “I like quiet so that I can focus and think properly. But the ID guys liked it.”

Satzger certainly did. “The energy of that room, the noise of the room made me work a lot better,” Satzger said. “I hated sitting back in my little space…. For me, the louder the noise the better.”

Jobs liked the music, too, but perhaps for different reasons.

“When Steve came in, he wanted the conversation to be between him and the person he was talking to,” said Satzger. “In all these open spaces, if it’s quiet, it’s really easy to hear what people are talking about. When he came in, we would turn the music up so that his voice would carry directly to one person only. You really couldn’t hear what he was saying.”

The studio visibly relaxed Jobs. “Steve in the ID space was a different person,” Satzger said. “He was a lot more relaxed and interactive. Steve had moods all the time. There were always things that were changing in how he approached people. But when he came in the ID space, he was always really comfortable.”

Jobs spent a lot of time in the studio, but when he was away, Ive used it as an opportunity to get some work done. “When [Jobs] went away, we would do 150-200 percent more work,” Satzger explained. “It was a good chance to blast stuff out and put new work, new ideas in front of him when he came back.”

The Iron Curtain

When the design studio moved onto the main campus, Jobs significantly beefed up security to prevent leaks. The studio is Apple’s ideas factory: the heart of the operation. Nothing must leak out. When the studio was on Valley Green, security wasn’t as tight. Visitors would get buzzed in by whomever was around. Jobs was determined that wouldn’t be the case in the new studio.

The vast majority of Apple’s employees are barred from the company’s design lab. Even some members of the executive team are forbidden from entering the studio. Scott Forstall, for example, who rose to be head of iOS software, wasn’t allowed to visit. His badge wouldn’t open the door.

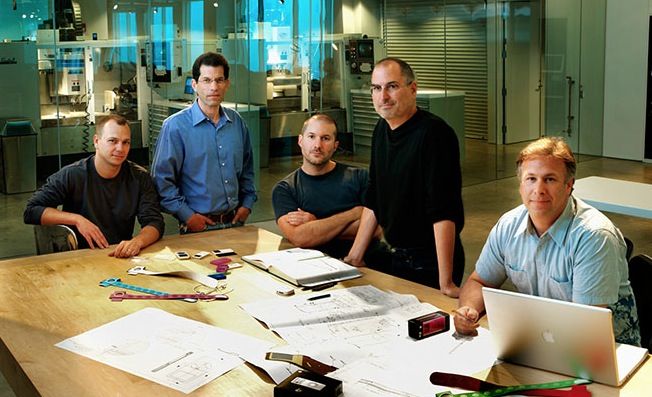

Very few outsiders have been inside the studio. Jobs would occasionally bring in his wife. Walter Isaacson was given a tour, but described only the presentation tables. The only known photograph of the studio was published in Time magazine. The photo shows Jobs, Ive and three other executives sitting and standing around one of the studio’s wooden project tables, with the shop in the background.

Photo: Objectified

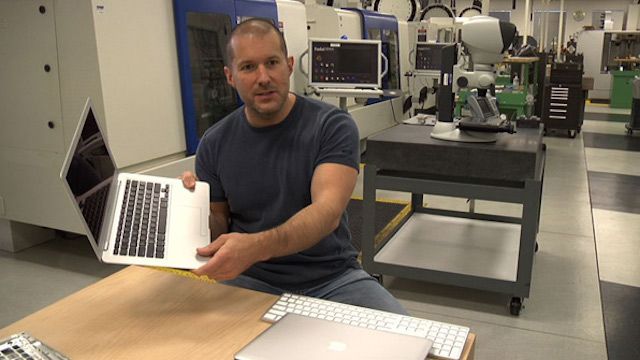

Ive occasionally gives interviews on Apple’s campus in an engineering workshop full of CNC milling machines. It’s been identified as the design studio, but it’s not. It’s an engineering workshop nearby.

When working on new products, the software engineers have no idea what the hardware looks like, and the engineers have no idea how the software works. When Ive’s team was making iPhone prototypes, they worked with a picture of the Home screen with dummy icons.

But the most secretive department of all is Ive’s group. “It’s locked down,” said Satzger. “People know not to talk about their work and what was going on inside Apple to the wrong people.”

The “wrong” people would be basically anyone but their direct colleagues, and sometimes not even them. Even Ive is forbidden from telling his wife what he’s working on.

A former Apple engineer who worked closely with Ive’s group in the Product Design team said the secrecy was exhausting. “Out of everything I’ve ever done in my life, I’ve never seen a more secret environment than working there,” he said. “We were constantly under threat of losing our jobs for revealing any shred of anything. And even within Apple, your neighbors often didn’t know what you were working on… The secrecy was like a gun to your head. Make one false move and we’ll pull this trigger.”

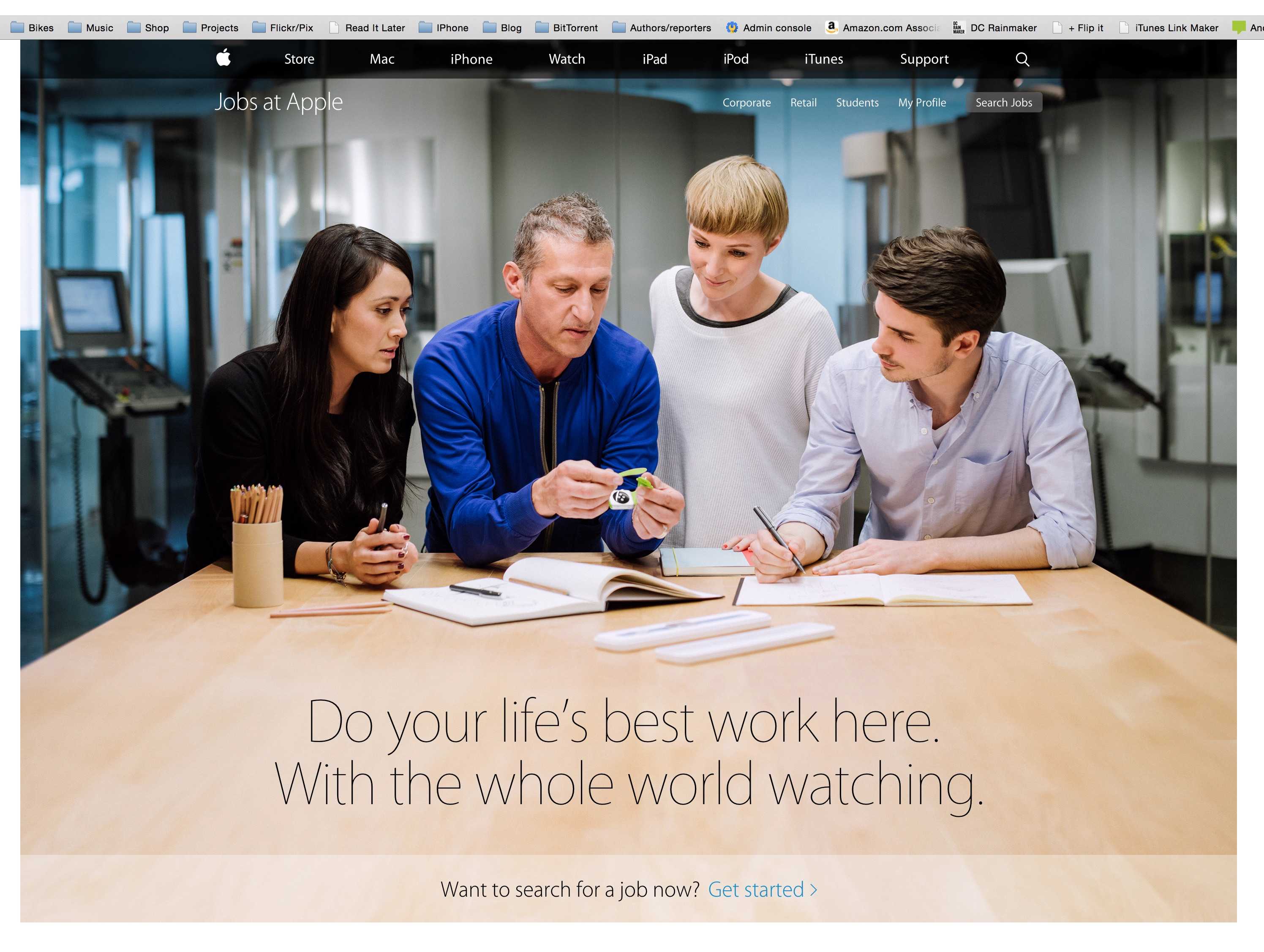

Apple’s policy means that the designers get almost no press, and very little public recognition. They’ve won every award under the sun, and they are known in design circles, but to the public, they are basically anonymous.

There’s little resentment about the lack of credit, though. The team is used to it. Ive is pretty gracious. He gets all the awards and recognition, but he always talks about the team. As one wag noted, the only time Ive says “I” is when he’s talking about the iPhone or iPad.

“We took it as, we’re all getting credit,” said Satzger. “[Apple] always says, ‘the Apple design team,’ but Steve never wanted us to be in front of the camera. They blocked headhunters and search people. Because we were blocked from facing media and hidden from headhunters and so on, we called ourselves the ‘ID team that’s behind the Iron Curtain.’”

It sounds pat, but Ive’s group works as a team and each member contributes to each product. Unlike when he joined the company, Ive no longer designs any of Apple’s products alone. Each product is designated a design lead, who does most of the actual work, plus one or two deputies, though weekly meetings ensure the design process is collaborative.

Biweekly brainstorms

Two or three times a week, Ive’s entire team gathers around the kitchen table for brainstorming sessions. All the designers must be present. No exceptions.

The brainstorms begin with coffee. A couple of the designers play barista, making coffee for the group from a high-end espresso machine in the kitchen. Daniele De Iuliis, an Italian from the U.K., is the coffee guru. “Danny D was the person who educated us all on coffee and grind and the color of the crema, how to properly do the milk, how temperature is important and all that stuff,” said Satzger, who was one of De Iuliis’ keenest disciples.

The sessions typically last three hours — from 9 a.m. to noon, or 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. — and are used to hash out whatever design problem Ive’s group is working on.

Ive runs the brainstorms, but he doesn’t dominate them. They are freewheeling, creative roundtables where everyone is expected to contribute. Ive rarely misses one, unless he’s traveling. “Jony’s always been involved in every design session,” said one designer.

The brainstorms are very focused. Sometimes it’s a model presentation, sometimes the detail of a button or speaker grille. There is never discussion of design philosophy. Blogs and magazine articles often note the influence of Braun’s Dieter Rams on Ive’s products, but Apple’s design chief never discusses design philosophy with the group.

None of the designers and engineers interviewed for this book said Ive ever espoused a particular design philosophy. Of course, all the designers are intimately familiar with Rams’ work and his 10 principles of good design; these have been drummed into the mind of every design student.

But each and every design at these Apple brainstorming sessions is approached on its merits. If there’s such a thing as a philosophy that drives Ive, it’s the desire to constantly simplify — to do away with as much as possible.

“[We] discuss our objectives, and so we can just be talking about what we would want a product to be,” said Apple designer Christopher Stringer. “That ordinarily becomes sketching, so we’ll sit there with our sketch books, and sketch and trade ideas and go back and forth. That’s where the very hard, brutal, honest criticism comes in and we thrash through ideas until we really feel like we’re getting something that’s worth modeling.”

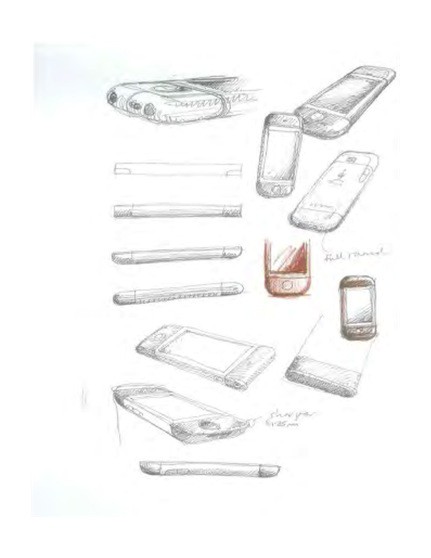

Sketching is fundamental to Apple design

Sketching is fundamental to the workflow of Apple’s designers. “I end up sketching everywhere,” said Stringer. “I’ll sketch on looseleaf paper. I’ll sketch on models. I’ll sketch on anything I can put my hands on, quite often on top of CAD outputs for want of better things to do.”

Stringer likes CAD printouts because they already have the shape of the product. “You’re working with something that already has the perspective set up and the views in a way that you can sort of add in lavish detail upon them,” he said.

Ive is also an inveterate sketcher. He’s good at it, but speed is the key. “He always wanted to get a thought down on paper so that people could understand it really quickly,” said Satzger. “Jony’s drawings were really sketchy, with a shaky hand. His drawing style was really interesting.”

Ive is skilled, but the artists of the group are Stringer, Richard Howarth and Matt Rohrback. Satzger describes Howarth’s sketchbooks as “works of art.”

“Richard Howarth would come in saying he had a crap idea and ‘you guys are going to hate it,’ but then shared these amazing sketches,” said Satzger, who called Ive’s sketchbooks “really cool.”

When the team was designing the iMac, the table was covered with loose sheets of copy paper for sketching, but Ive’s group uses hardbound sketchbooks. Most use canvas Cachet sketchbooks from Daler-Rowney, a small British company. The studio’s office-supply stockroom is stacked with them. They are made from high-quality canvas; being hardbound, they don’t fall to pieces. (Ive uses a blue sketchbook that’s about three times as thick as the Cachet sketchbooks and boasts a ribbon to mark a certain page. Howarth uses the same type of sketchbook.)

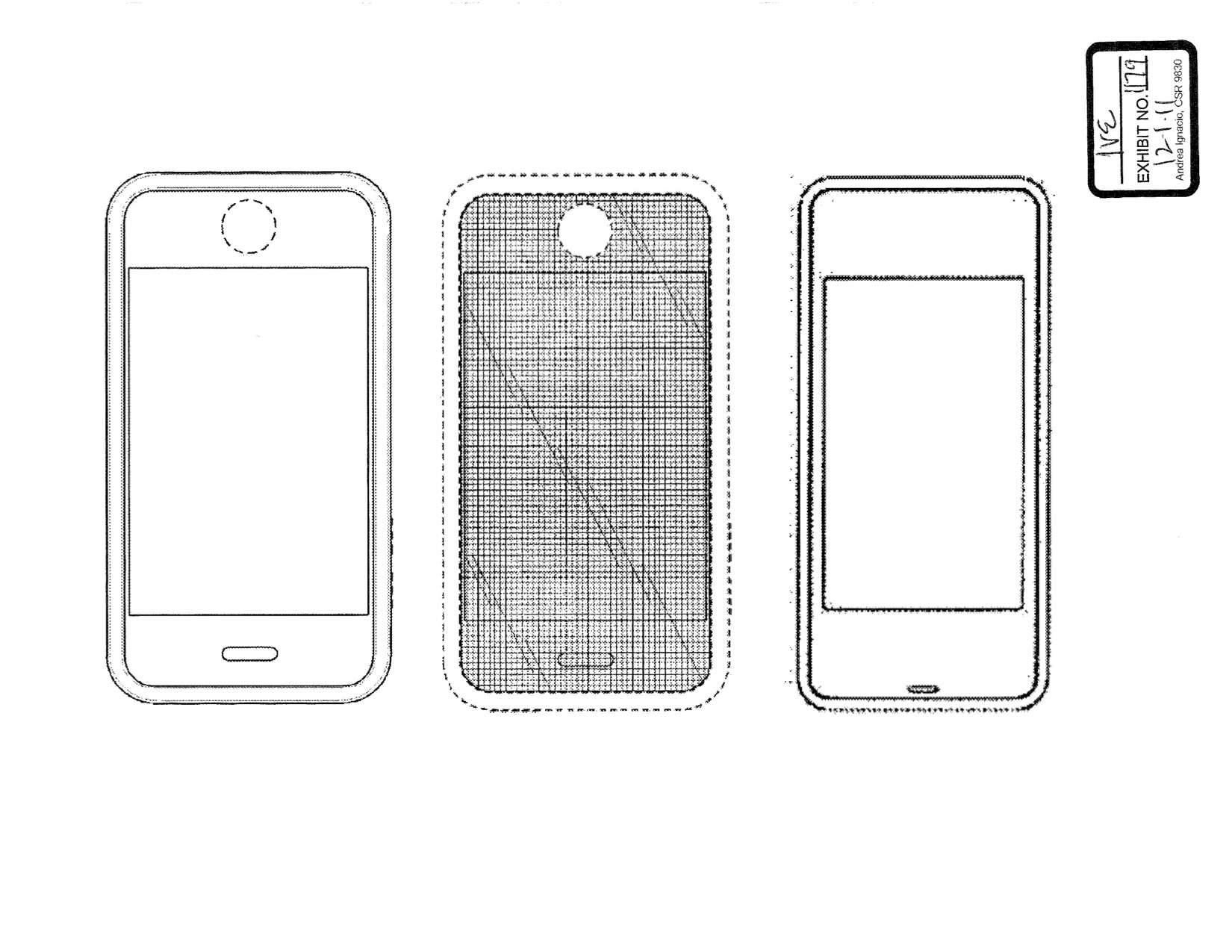

The hardbound sketchbooks make it easy for members of Ive’s group to go back and look at their ideas. They document everything. The sketchbooks became a contentious issue during the Apple-Samsung trial.

A lot of sketching happens in these sessions. At the end of the brainstorm, Ive will sometimes instruct everyone around the table to copy their sketchbooks and give the pages to the lead designer on the project under discussion. Afterward, Ive will sit with the lead designer and carefully go through all the pages. Most major projects have a lead and two deputies, who will also pore over the pages, trying to find ways to integrate new ideas.

“Some days I’d be engaged and have 10 pages of stuff,” said Satzger. “Sometimes you could feel when a designer wasn’t engaged in the material, when they weren’t filling up pages of things.”

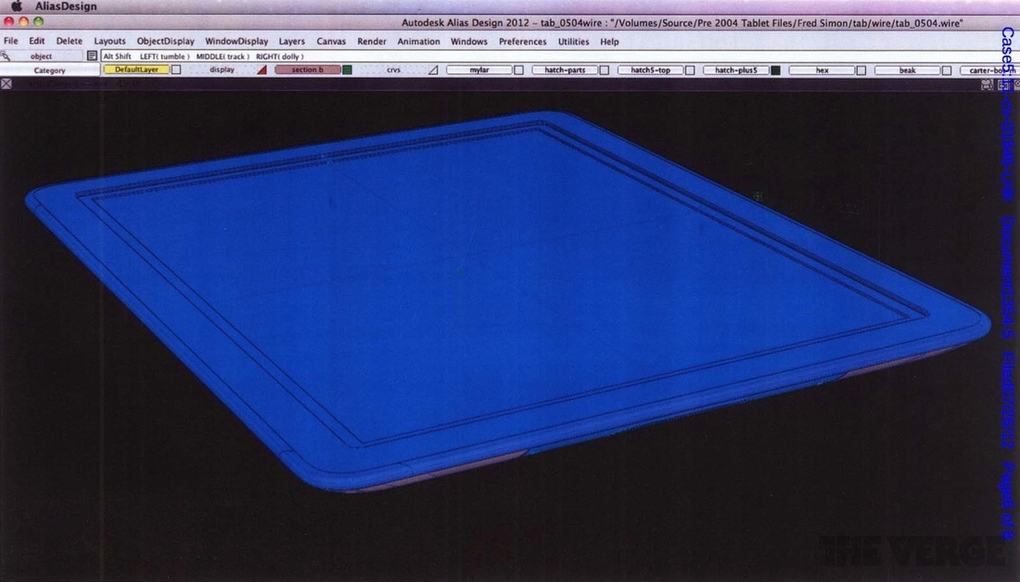

The most promising ideas are taken to the CAD group next door, where sketches get turned into a 3D model. The model is then sent to the machine shop, where it creates a “tool path” for one of the CNC milling machines to cut the shape out of RenShape foam board or ABS plastic to validate the basic size and shape. A “tool path” is just what it sounds like — a path determined by the computer that the cutting tool follows to create the desired shape.

Photo: An early iPad CAD file, shown in evidence during the Apple/Samsung trial.

Although CAD operators make up about half the staff in the studio, there’s a clear division between them and the designers. The CAD sculptors are not afforded the same special status; they are in service of Ive’s design team. “There are a few designers that are capable of creating CAD themselves, but it’s not a requirement,” said designer Stringer during the Apple-Samsung trial. “In fact, most of us don’t. It’s a skill you need to dedicate significant time to just to understand the craft of CAD. We prefer our designers to be thinking, so we have a dedicated team for this.”

The CAD group is separate, and its members keep to themselves. They rarely attend meetings and are kept in the dark (metaphorically and literally: The CAD studio has very low-level lighting).

Realistic mockups of possible Apple products

When the group is ready to present ideas to an Apple executive, they outsource to a model shop that specializes in making realistic mockups. They want the models to look as much as possible like a final, finished product, and that requires specialist equipment and skills.

Ive’s group frequently uses Fancy Models Company, a highly respected model-making company based nearby Fremont, California. Most of the iPhone and iPad prototypes were made by Fancy Models, which is run by Ching Yu, a modelmaker from Hong Kong. Each model costs around $10,000 or $20,000. “Apple spent millions on models made by that company,” said a former designer.

By contrast, the CNC machines at Apple, although capable of making pretty refined models, are used mainly for parts that are needed quickly — a lot of plastic shapes and smaller aluminum bits. Apple’s CNC machines rarely produce final models.

When it comes to choosing the right design, the finished models play a crucial role. For example, when designing the Mac mini, Ive had about a dozen models made up in different sizes. The Mac mini is Apple’s “headless” Mac: a small aluminum box that comes without a monitor or keyboard and mouse; customers supply their own. It’s a relatively inexpensive product; at many companies, such a product would be low on the totem pole.

Yet Ive had about a dozen Mac mini models made up, ranging from very large to very small. He had the models lined up on one of the presentation tables in the studio. “We were there with some of the VPs and Jony,” said a former Apple product design engineer who requested anonymity. “They pointed at the smallest one and they said, ‘Well, obviously that is too small, that kinda looks ridiculous.’ Then they pointed at the other side and said, ‘Well, that’s too large, no one wants a computer that big. How do you find what’s right in the middle?’ And they talked through that process.”

The decision about the size of the case seems faintly ridiculous, but it would influence what kind of hard drive the Mac mini could contain. If the case was large enough, the computer could be given a 3.5-inch drive, a size that’s commonly used in desktop machines (and is therefore relatively inexpensive). If Ive chose a small case, the mini would require a 2.5-inch laptop drive, which is much more expensive.

Ive and the VPs selected an enclosure that was just 2mm too small to use a less-expensive 3.5-inch drive. “They pick it based on what it looks like, not on the hard drive, which will save money,” said the engineer, who said he didn’t even bring up the size issue because it wouldn’t have made a difference. “Even if we provided that feedback, it’s rare they would change the original intent,” he said. “They went with purely aesthetic form of what it should look like and how big it should be.”

Size considerations even influence things like the camera on the iMac. The desktop computer’s front-facing camera above the screen is used for videoconferencing.

Another Apple engineer, who also asked to remain anonymous, worked with Ive’s team on adding a camera to the iMac.

“The biggest challenge was how small Steve Jobs and the ID group wanted the opening for the camera to be,” he said. “The size of the opening had to be as small as possible for aesthetic reasons, which should come as no surprise. I have little doubt that if the opening could have been made invisible, it would have been.”

The design process is not linear. On a fundamental level it starts with a brainstorm and sketching, leading to finished models that show the form and finish of a proposed product.

However, the process is extremely fluid. Products are often explored in several parallel directions; they are restarted or scrapped. “These processes, though they seem very linear, and in instances can be, typically aren’t because we’ll go back and forth,” said Stringer. “We’ll even sketch on models. We’ll combine a part model and a sketch from another sketch book from a different design session. It’s back and forth. It’s nonlinear. It weaves and knits its way along the design process, ultimately to a point where we feel really satisfied that we have something special.”

Jony Ive’s evolving role at Apple

In recent years, Ive’s role has become more managerial than design-driven. He doesn’t design any of the products alone, but he adjudicates every single design decision the group makes. Nothing is done without his input, whether it’s the color of a product or the detail of a button. “Everything is reviewed by Jony,” said one of the designers.

Ive runs the group and recruits new members. He is the conduit of information between the design group and the rest of the company, especially at the executive level. He worked very closely with Jobs when he was alive, and continues to do so with current Apple executives, to select what products to work on and what directions the company should take.

“Every design idea goes through Jony,” said Satzger. “An early methodological failure used to be that there were lots of good designers at Apple, who were all allowed to work on different things simultaneously. There was no control over these people. Later, Jony became involved in every design session, and the team took everything he said very seriously.

“Jony is very effective as a leader. He is a soft-spoken English gentlemen who had Jobs’s ear. He never managed people like he was the boss. He was pretty neutral. And he treated everyone’s opinion as important. He would sit down with people and begin with, ‘Steve’s not happy with where we are. We need to start building models and come up with new ideas. We need to do something different.’ Then for the next week, every day the team would have all-morning design sessions.”

In many ways, Ive was the hand implementing Jobs’ vision. If Jobs didn’t like something, he’d say so, but that was the only direction he gave. He pushed Ive and his designers to come up with the right solution.

On many occasions, Ive managed up. “A lot of times, it was Jony who would drive Steve,” said Satzger. “He might say to Steve, ‘I think we should change this,’ if he felt that it was important to do something different.’”

Jon Rubinstein, Ive’s former boss, described Ive as a great leader of a small, close-knit and extremely talented team. The Apple designers work well together and were “obviously having fun doing really cool designs.”

“Jony is a good leader,” he said. “He is a brilliant designer, and his team respect him. Jony has very good product sense. And when he is immersed in the design process, his work is a collaborative effort. Although in the press Jony gets all the credit, in reality his whole team does a lot of work. They are a talented team that does brilliant work together. They all contribute tremendously with great ideas.

“It is very iterative process. It is lots and lots of different designs, lots of different directions. We as a team would get together: Me and Steve and Phil and Jony would get together and go through the designs and Jony’s team would evolve a direction. And we’d do that again and again until we finalized what it was going to look like.

“As a personality, Jony Ive is low-key. He hides the ego behind that. He can be a very intense guy…. He is soft-spoken, but also very firm in his beliefs. He jokes occasionally, but mainly has a serious comportment. He was always very focused on his career, and aware of the politics to move up within the company. The public persona of Jony Ive stating that all that matters to him at Apple is design — is nonsense. He was very focused on his career.”

A tight-knit group

Ive’s group is extremely tight. Insular isn’t the word. They work together, eat together and socialize together. Every day, four to eight of the designers go to lunch together, usually at the Apple cafeteria, though they generally don’t mingle with other staffers. They eat at their own table.

The designers socialize together after work, especially those living in San Francisco. For many of the designers, social life and work are one. That includes Ive.

“If I did something, unless my wife arranged it, it was with them all,” said Satzger. “The SF group was a lot more tight. Bart, Chris and me hung out. Danny and Jony and Richard and Matt got together all the time and saw Eugene. Duncan was more independent. They liked drinking a lot of champagne and spent a lot of time at Le Colonial,” a stylish French Vietnamese restaurant in San Francisco.

“At MacWorld we’d get a limo and go,” said Satzger. “The limo was full of Bollinger champagne. We’d drink and go to dinner somewhere, then end up in the Redwood Room [a cocktail bar in San Francisco’s Clift Hotel] and drink some more. We’d reserve it whenever Jony’s friend Marc Newson was in town. Then we’d end up at the Clift Hotel and Bart or Jony would rent a room and the design team, and maybe a couple other people, were always there.”

The anonymous former product design engineer remembers being at a black-tie event at the Clift Hotel. “Around midnight, in rolls the ID crew for the after-party that is going on in the hotel lobby,” the engineer said. “Stringer, Ive, Whang and a bunch more were there. I’m asking Ive, ‘What are you doing here?’ They just roll out at night and do select, exclusive barhopping. They had a reserved area. They’re always very trendy, into trendy music.”

16 responses to “How Apple’s super-secret Industrial Design team really works”

Where do Apple’s great products come from?

Like?

I don’t see the point in such secrecy anymore considering most of Apple’s products are leaked 6 months in advance from China. The Apple Car leaked 5 years in advance.

Whatever happened to Tim’s “doubling-down” on secrecy?

It was leaked that Apple was working on a car, but because there have been no specific details, this rumor is of little value to competitors. We also heard that a smart watch was eventually forthcoming, but that was the extent of it. Maybe the rumors caused competitors to rush theirs to market beforehand, but that hasn’t seemed to have hurt Apple. None of those first gen watches resembled the Apple Watch.

Apple’s suppliers have certainly leaked details (often photos or early samples of parts), but by the time those become public, Apple already has a good head start on the competition. Just because some leaks are inevitable is no reason to abandon secrecy altogether. It would certainly be worse if specific designs were leaked by Apple engineers earlier in the development phase.

Competitors have always tried to copy Apple’s ideas. To the extent that Apple can keep things secret longer, it gives them more lead time to establish themselves before the inevitable clones hit the market.

So all those people looked at the Apple watch and thought “Wow, that’s something to be proud of”. Then they started on the iphone ‘smart case’ and really thought outside the box.

so true, i don’t know where their heads were when they designed that case, apple has gone off the grid from what Steve originally planned, i think it’s going to get even worst in the coming years.

Leander:

“Biweekly brainstorms

Two or three times a week, Ive’s entire team gathers around the kitchen table”

“Bi-weekly” means – once every two weeks.

“Semi-weekly” means – once every half week, or two times per week.

bi-weekly also means twice a week. A simple search would reveal the following:

bi·week·ly

bīˈwēklē/

adjective & adverb

adjective: bi-weekly

1.

appearing or taking place every two weeks or twice a week.

“a biweekly bulletin”

noun

noun: bi-weekly

1.

a periodical that appears every two weeks or twice a week.

No. The definition that you found to attempt to justify “bi-weekly” is a result of too many ignorant people misunderstanding what the correct word is.

This is similar to when some people saying “further” when they should be saying “farther.” They are two different words that are spelled differently for a reason, just like semi-weekly and bi-weekly are two different words that have two different meanings.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xSnraJOeOyM#t=33s

Look up ‘pedant’ while you’re at it.

Maybe Ive needs to grow a pair of balls and tell some of his designers that their ideas aren’t worth a pile of s*** because you can’t treat every idea with respect. You know you’re behind the 8-ball when the world of smart watches starts moving towards a circular face and you are standing there trying to justify your rectangular design because it uses a “list based interface”.

LG, Motorola, Oglio have proven that you can have a stylish, beautiful, functional smart watch with a circular face. The Apple Watch isn’t insanely great. So many people buy it and then return it because it isn’t all that. Nobody wants that thing, and who came up with the idea of an $18k smart watch?? WTH?? Ive and team is drinking a little too much champagne. Someone needs to check this guy.

Well… It is a nice design. And that so called bad idea is selling frekin gang busters compared to any of those other brands LG, Motarola, Oglio etc. Hell, the way this watch is selling, many people must like its design, and I’m one of them.

Don’t tell me these guys designed the new magic mouse and the new battery case….

No that was outsourced… to Microsoft

haha good one

Hell NO!!! Microsoft is making seriously impressive hardware (recently) ……

Marc Newson * edit