SAN FRANCISCO — The iPhone has changed the way we do everything, from finding a date to finding a meal. Now it’s about to change the way innovative hardware gets made.

With smartphones manufactured in such massive quantities, basic components like chips and batteries have become dirt cheap. Smartphones also allow hardware to be dumber by providing processing power and a big screen. Add 3-D printers (which ease prototyping), crowdfunding (which has shaken up financing) and Github (for sharing software), and you’ve got a smartphone-fueled manufacturing revolution in the making.

“It’s the cellphone peace dividend,” said Brady Forrest, a former venture capitalist who heads up Highway1, an “incubator” for hardware startups that launched a few months ago here in the city’s Mission district. “So many are being made, prices for components are plummeting.”

Hardware has always been hard. Unlike software companies, which can be launched with a laptop and credit card, hardware companies require resources and infrastructure — factories, supply chains, distribution channels. But the rapid transformation catalyzed by the iPhone is altering the dynamics of the hardware business. It’s a big change, exemplified by the burgeoning Maker movement.

It’s also a big opportunity for Highway1, an unusual San Francisco enterprise located in a big, old warehouse near 17th and Harrison streets, an area hopping with hip startups. Launched in the spring, Highway1 is working with 12 small teams of would-be entrepreneurs. For four months, the 12 teams get office space, up to $50,000 in seed money (in return for equity) and access to a $3 million machine shop upstairs. Highway1 also offers myriad mentoring and support functions, plus the community of a dozen other startups in the same boat. Highway1’s second class of startups just graduated on Wednesday.

Gesturing with his hand around the big open office space, Forrest explained that Highway1 wants to be like Amazon Web Services — a basic infrastructure for physical products.

“We want to de-risk hardware,” he said.

When Amazon Web Services launched in 2006, it spurred a revolution for Web startups. No longer did small companies have to invest in expensive servers or data centers; they could rent it on-the-fly from Amazon. AWS helped hundreds of small companies get off the ground or scale up, including Pinterest, Airbnb and Shazam.

In the same way, Highway1 wants to provide help and resources to develop the next Pebble Smartwatch or Ouya, the Android games console. In four months, the startups go from conception to prototype and get ready for production.

“There’s a big jump between making one and making 1,000,” said Forrest.

Highway1’s first graduating class included the Skylock, a connected bike lock. The first Skylock prototypes were built out of Lego and wood. Now the lock is getting ready for manufacturing.

“That’s what we’re here for,” said Forrest, “to get that product ready for production.”

Highway1 is a spin-off of PCH International, the supply-chain giant based in Ireland and China that provides parts for Apple, Beats Electronics and dozens of other giant CE firms.

PCH hopes to nurture the next generation hardware makers, turning them into bigger businesses over time.

During our visit, we met half-a-dozen of the fledgling firms. They were working on everything from an LED-bejeweled handbag to a hackable keyboard “designed not to cripple you,” according to its inventor.

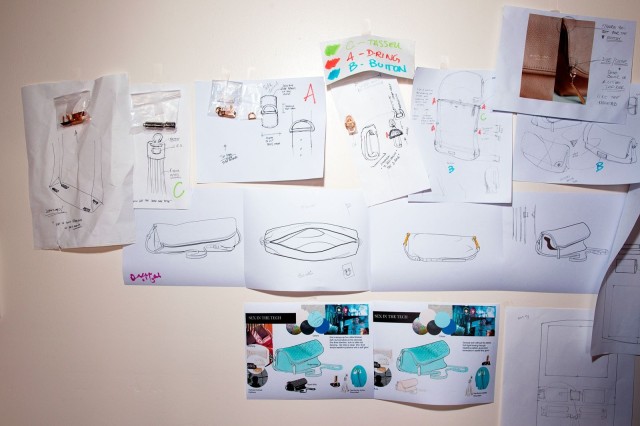

Typical was the team behind Podo, a tiny Bluetooth camera that can be propped on a table or stuck on a wall. The three young founders of the company were all living together when they conceived of an “stickable” camera. Instead of asking strangers to take photos for you, the Podo camera can be stuck on any surface and controlled from a distance.

“We wanted a flexible, cheap imaging device,” said CEO Jae Hoon Choi, a recent economics graduate from Berkeley. “A camera that you can do what you want with it.”

The Podo team have already raised more than $1 million in financing, and hope to go into production later this year. They are experimenting with using multiple Podo cameras to take multi-camera action shots — something Forrest described as “a new type of photograph.”