This story first appeared in Cult of Mac Magazine

Architecture hasn’t really ever been important in the brick and mortar-averse tech industry. It wasn’t all that long ago that digital utopians proclaimed physical geography dead altogether, with a vocal minority apparently pleased to leave the actual world behind them and embrace the cyberspace of William Gibson’s Neuromancer.

It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that the technological breakthroughs of Silicon Valley have advanced almost inversely to the region’s architecture. In a brave new world of lush rolling hills and the always impressive San Francisco Bay, the most that the majority of companies have managed to come up with are drab industrial parks filled with two-story, cubicle-lined buildings.

This post contains affiliate links. Cult of Mac may earn a commission when you use our links to buy items.

Want to escape notice by housing your startup in a colorless identikit office block? There’s (probably) an app for that.

“The reality is that most of the big tech companies in the Valley, not just Apple, have an extreme indifference to place-choosing to locate operations in suburban office parks,” American architectural design professional Adam Nathaniel Mayer noted in an article for the Los Angeles Times published earlier this year.

“This has much to do with the history of Silicon Valley planning as it does with the nature of tech companies, which tend to employ legions of introverted computer engineering types and go to great lengths to remain insular and secretive” — adding that Apple takes this notion to the extreme.

Apple Wasn’t Built In A Day

But if this has typically been the case, it is a situation which may well be changing as a number of companies (perhaps directed by Apple’s focus on the importance of design, or just a desire to expand their cultural reach) have apparently realized the “value added” benefits that good architecture can bring.

Google, for instance, has hired noted architects HLW to design its offices in New York with life-size taxi murals, built-in QR code signs on the wall, and soundproofed, windowless room full of drums and electric guitars, making it look more like a hip advertising agency than a classic home for geeks and programmers.

In Mountain View, the company meanwhile owns the eye-catching (and frankly bizarre) headquarters constructed by Silicon Graphics during its 1980s peak, and described by technology writer Steven Levy (In the Plex, 2001) as looking “as if a playful hacker had gone overboard with a CAD program.”

Facebook, too, is keen to show off its architectural street cred as of late by reaching out to Guggenheim Museum architect Frank Gehry to design a 3,400 employee engineering office connected to its Menlo Park Headquarters by way of an underground tunnel. All of these headquarters evidence a sense of high tech fun that mesh with and convey their companies’ ethos and culture.

Apple now joins the ranks of this latter group. With its new “spaceship” headquarters, Apple finally has a home base to rival that of any of the above constructions: a literal embodiment of the company’s long-time address at Infinite Loop.

It is also worth asking what this grandiose new building means for Apple, particularly in light of the recent disappointing financial quarters (in the eyes of certain Wall Street analysts at least), and news that other companies like Samsung are doing an alarmingly good job of impinging on areas in which Apple once seemed securely dominant.

In the same way that it was only in the latter years of Rome when the most spectacular gladiatorial shows took place, so too can an impressive headquarters (literally a monument to one’s crowning achievement) seem like a sign of imperial hubris.

Certainly it is possible to point to a number of companies whose construction of ambitious, world-beating headquarters coincided almost exactly with the start of their precipitous decline. The New York Times Company’s stock price went into a tailspin shortly after it moved into its Renzo Piano building, and it currently leases its headquarters to a number of outside parties. A similar fate befell AT&T, which broke up after moving into its grandiose “Chippendale skyscraper” on Madison Avenue, while General Foods collapsed after occupying the Kevin Roche-designed glass and model building constructed for it in Westchester County.

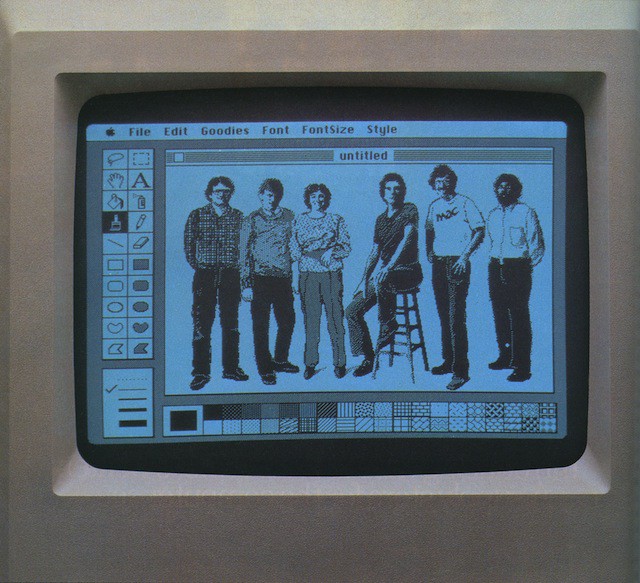

Even Steve Jobs has fallen prey to this thinking once before. During Jobs’ NeXT days, he hired noted Chinese-American architect I.M. Pei to design a freestanding staircase for his company headquarters (a clear predecessor of the staircases found in today’s Apple Stores), had a long-closed quarry reopened to extract a piece of granite big enough to serve as a conference table, and paid $30,000 to have a freshly-laid tiled floor torn up and replaced because, in his words, “the grout [was] the wrong color.”

At the time, one of NeXT’s biggest retailers had managed to sell just 360 computers in total.

The More Things Change

Few people (least of all this writer) are going to compare Apple’s new headquarters to that of the fundamentally-flawed NeXT, or suggest that Apple is one chariot race around its new circular campus from falling into Rome-like ignominy. But this is the line of questioning that seems to recur most often to the architects who have so far commented on the company’s new headquarters.

One example is the Los Angeles Times’ architecture critic, Christopher Hawthorne, who has publicly referred to Apple’s new headquarters as a “retrograde cocoon,” thereby prompting the immediate follow-up question: what is Apple metaphorically hiding from or gestating into?

There is a line in the cult-classic film This Is Spinal Tap about amps that go up to eleven. This may well be the best way to read Apple’s new headquarters, too, since what it does very well is to articulate Apple’s corporate ethos on a grander scale than ever before.

The campus may not have the giant-sized sci-fi props, in-door rock climbing walls, or between-buildings zip-lines of Google (the latter concept was quickly shut down by the city of Mountain View), but then Apple is not Google. According to Benjamin Feenstra, architectural blogger and co-founder of Kiozk.com, what is interesting about Apple’s new headquarters is not what is different, but what is the same.

“From a distance the new campus looks almost anti-Apple,” he told Cult of Mac. “It is made up of glass, which seems very new for a company known for its secrecy. But if you look closer what you will see is one shape–thereby enabling everyone to feel that they are part of one big company, rather than the Google campus where people are spread out–very cleverly divided into eight separate buildings inside. This means that privacy can be maintained, and it is also possible for everything to be controlled in the way we associate with Apple.”

These similarities extend even to the floor plans Apple and architect Norman Foster have created: borrowing from the existing layout of Infinite Loop, but pulling everything much closer together.

“The current campus is six buildings centered around one big atrium,” continued Feenstra. “The new ‘spaceship’ campus, meanwhile, is eight buildings, divided by nine mini-atriums, all under one big roof. It’s essentially the same design that they are currently using–just enacted on a far grander scale.”

Steve Jobs also talked about the Stanford University campus being a major source of inspiration when it came to designing the new headquarters.

“The purpose with the Stanford campus was to create a sort of bubble that would keep students away from distractions and focused on their studies,” John Barton, director of the Architecture Program at Stanford, told Cult of Mac. “At the same time Stanford has always been big on the notion of interdisciplinary work and development across departments.”

Both of these, it might be said, prove true at Apple, where, despite the strict confidentiality that binds individual divisions, all products bear the marks of Apple DNA.

Symbols of Excellence

With its new headquarters, Apple (by way of architects Foster + Partners) has created a grandiose centerpiece to its empire that resembles nothing more than an Apple product in its striking simplicity and design obsession. Again, while this remains previously unexplored territory in many ways, its adherence to the Apple DNA means that it fits into the existing company as easily as a new portable music player or smartphone, fitted into a company that had previously made only computers.

Even during the days of Apple’s earliest offices on Bandley Drive in the early 1980s, Steve Jobs filled the space with designer flourishes such as a BMW motorbike, set of framed black and white prints by photographer Ansel Adams, and a Bösendorfer piano worth $80,000, playable only by the Mac team.

“These were things I would refer to as symbols,” said former Mac engineer Andy Hertzfeld when I interviewed him for my book The Apple Revolution. “Steve was always thinking about the best way to inspire his team and how to reflect our values, which were really his values … They were symbols of excellence.”

“Apple has done nothing more or less than build the biggest ever Apple product,” Benjamin Feenstra told Cult of Mac. “When I first watched the video Apple presented to the Cupertino council it suddenly hit me: what Apple has done isn’t to design a new office, but to design a product. Steve Jobs himself said he felt Apple had a shot at making the best office building in the world. That’s not something you hear about often with corporations. But just like the iPod, the iMac, and the iPad share design DNA, so too does Apple’s new headquarters: it needs to be simple for its users, it has to beautiful, it has to be the best of its type that can possibly be built. For me, there is no difference between an iPhone and the iCampus.”

Apple’s new headquarters doesn’t just cement the company’s place atop the high-tech world while demonstrating the new commitment to sustainable resources, but it also aims to inspire those working inside it to keep on creating better and better products.

As Apple has broadened its remit and product lines over the past 12 years, so too has the importance of bringing all these disparate departments under one roof increased. Apple no doubt hopes that its new spaceship headquarters will be an image of this, a sign that, unlike the first time Jobs departed the company, Apple is a unified organization unlikely to descend in fiefdoms any time soon.

And much the better for it.