Michigan State University baseball coach Danny Litwhiler was reading the campus newspaper one day in 1974 when he decided to call the cops on some of his pitchers.

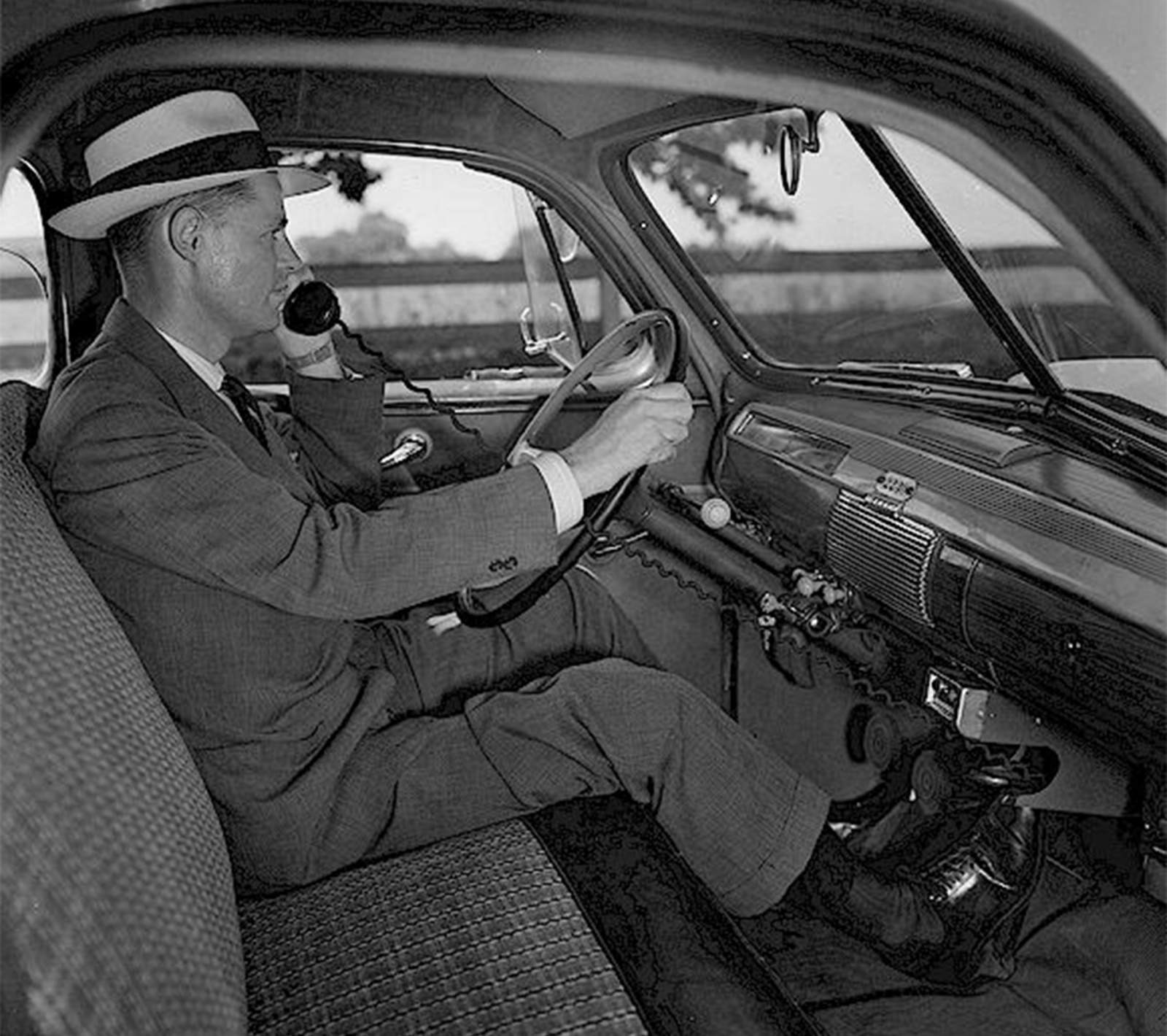

An article and photo of campus police showing off the department’s new radar gun to catch speeders caught Litwhiler’s eye and he wanted police to swing by the ballpark with the new toy to see if it could read the speed of a pitched baseball.

An article and photo of campus police showing off the department’s new radar gun to catch speeders caught Litwhiler’s eye and he wanted police to swing by the ballpark with the new toy to see if it could read the speed of a pitched baseball.

Litwhiler – a flawless defensive player in the bigs who evolved into a beloved college coach – changed the game of baseball that day. No longer would myth and mystery surround the fastball. Pitchers, for better or worse, would be scouted and evaluated based on a new number – miles per hour.