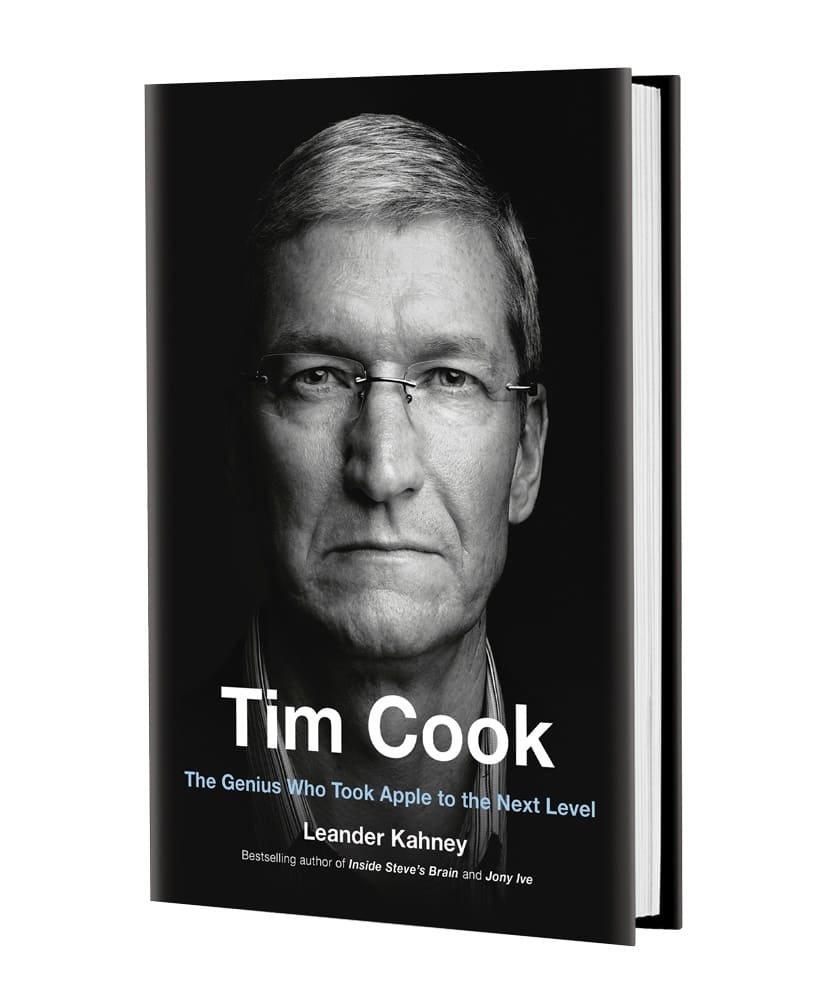

This post was going to be part of my new book, Tim Cook: The Genius Who Took Apple to the Next Level, but was cut for length or continuity. Over the next week or so, we will be publishing several more sections that were cut, focusing mostly on geeky details of Apple’s manufacturing operations.

This post was going to be part of my new book, Tim Cook: The Genius Who Took Apple to the Next Level, but was cut for length or continuity. Over the next week or so, we will be publishing several more sections that were cut, focusing mostly on geeky details of Apple’s manufacturing operations.

Foxconn was founded around the same time as Apple, although 6,000 miles away on the other side of the world. In 1974, when 19-year-old Steve Jobs was working at Atari, 24-year-old Terry Gou borrowed $7,500 ($37,000 in today’s money) from his mother to start up a business.

Gou was born in Banqiao Township, Taipei County. His parents lived on mainland China’s Shanxi Province, before fleeing to Taiwan in 1949, one year before Gou was born. He was the oldest of three brothers, with two younger siblings, Tai-Chiang and Tony, who also went on to become businessmen. Gou’s father was a police officer, and the job evidently paid well enough that Gou was able to get an education up to college level. Instead of pursuing university, however, he attended a vocational school that taught student to be sailors.

With three years of vocational training and two more years as a shipping clerk under his belt, Gou decided to strike off on his own and start a business; hoping to grab a piece of Taiwan’s burgeoning export economy. His idea, perhaps not world changing but certainly profitable, was to make the small plastic knobs used to change the channels on black and white television sets. With his $7,500 capital, Gou bought two plastic molding machines and set to work with 10 employees.

His first customer was the Chicago-based Admiral TV, and he rapidly managed to convert these initial orders into orders for other companies as well. Early supply deals included RCA, Zenith, and Philips. Gou was tenacious and ambitious. His personal hero was the Mongolian warlord and conqueror Genghis Khan, who united the nomadic tribes of Northeast Asia in the thirteenth century and launch the Mongol invasions that conquered most of Eurasia. As a tribute to Khan, and a personal reminder of his success, Gou wore a beaded bracelet on his right wrist which came from a temple dedicated to Khan. As well as ambitious, however, Gou was also charismatic and likeable, and this combination allowed him to turn his company Hon Hai into a successful contract manufacturer.

Preorder Tim Cook book

Leander Kahney’s new book about Apple’s CEO will be released on April 16, but you can preorder it from Amazon today. “If you’re interested in a great overview of Tim’s still-ongoing tenure at Apple, Leander Kahney’s latest book is exactly what you need …. I highly recommend it.” — Paul ThurrottGou had a work ethic second to none, and he expected the same level of commitment from those who worked for him. A saying at Foxconn was that the first year was a honeymoon, the second year you worked like a tiger, and the third year you worked like a dog. Employees could get stock options in the growing business, but in order for these to vest they had to work for the company for several years. In a 2002 Bloomberg interview, Gou boasted that he worked 15-hour days, six days a week, and that he hadn’t taken off more than three days for vacation since starting the company in 1974. “You need real discipline,” he said. “A leader shouldn’t sleep more than his people; you should be the first one in, last one out.” Even years later, when he was rich beyond his imagination as a young man, following the notorious suicides at the Foxconn factories, Gou slept in his spartan office in Shenzhen in a makeshift bed on the plain cement floor. He was telling those who worked for him that he was willing to share in their hardship.

Foxconn’s business continued to grow. In the early 1980s, Terry Gou visited the United States for the past time, and toured 32 states over the course of a mammoth 11-month visit. Showing impressive chutzpah, he frequently dropped in on companies unannounced, travelling in a Lincoln Town car which he rented in every city in turn. He learned to speak most of his English during the trip. “He is really one of the top sales guys in the world,” said Max Fang, the former head of procurement for Dell in Asia, who has carried out business with Gou. “He is very aggressive and always on your tail.” Quanta chairman Barry Lam evidently agrees with the assessment. “I learn a lot from him,” he has said. “He knows very well how to expand the business and how to keep down costs.”

Shenzhen

Although Foxconn is headquartered in New Taipei, Taiwan (in a gritty suburb called Tucheng, which in Mandarin means “Dirt City” ), the place it is most synonymous with is Shenzhen, a major city in Guangdong Province, southeastern China, immediately north of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The rise of Foxconn from successful contract manufacturer to the world’s largest contract electronics manufacturer and single largest employer in mainland China is indelibly linked with the modern story of Shenzhen.

No city anywhere in the world is more associated with manufacturing of consumer electronics than Shenzhen. When Foxconn started in the 1970s, Shenzhen was a fishing port outside Hong Kong. Its population was around 300,000, about the same as Cincinnati, Ohio or Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Today, it is home to 11.91 million people and produces 90 percent of the world’s consumer electronics gadgets. It is China’s third largest city after Shanghai and Beijing.

What transformed Shenzhen from medium-sized port to manufacturing megacity was a 1979 decision by China’s Communist Party leader Deng Xiaoping to designate the city the country’s first Special Economic Zone, opening it up to capitalism and foreign investment to fuel growth and development. Part of an economic overhaul, China’s Special Economic Zones differed from the rest of the country because they acted relatively independently, compared to trade elsewhere in China, which was tightly controlled by the nation’s centralized government. The Special Economic Zones promised low-cost labor, cheap land, access to ports and airports for easy exporting of products, reduced corporate income tax, and other tax exemptions. As planned, they helped to transform China’s economy.

Foxconn was by no means the only company to move to Shenzhen to capitalize on this new haven of capitalism, but it was certainly one of the chief beneficiaries. In 1988, it opened its first offshore factory in Shenzhen. It employed a comparatively small workforce of 150 migrant workers from the countryside in Guangdong province. Around 100 of these employees were women. Despite its tiny size compared to Foxconn’s Shenzhen twenty-first century factory (at its height, Foxconn’s sprawling 1.4 square-mile flagship plant, just outside Shenzhen, employed around 450,000 workers ), the Shenzhen factory nonetheless set out a format that has continued: combining both factory floor and dormitory-based living accommodation for its workers.

In some ways, Shenzhen was a dream for Foxconn, but it still represented a risk. A lot of Taiwanese companies didn’t dare to expand into China. As the labor market in Taiwan tightened and wages were driven up during the 1980s, many local manufacturers moved instead to Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines. China’s relative lack of infrastructure and unpredictable communist government served as a deterrent to Taiwanese companies who might otherwise go there. Politically, the situation between China and Taiwan was complex. Beijing viewed Taiwan as a province that should be reintegrated back into the official mainland — even if this involved force.

Nonetheless, Gou persevered. During the 1990s, Foxconn underwent explosive expansion. Shenzhen attracted large numbers of arrivals from around China, excited by the plentiful work opportunities and chance to learn a trade in a fast-growing sector like consumer electronics. Foxconn was able to take advantage of this massive influx of cheap labor and grow massively.

“I’m sure you have seen some of the old footage of the Ford company where you had guys all lined outside the wall,” said Duane O’Very, a former Foxconn manager who worked at the plant at the time. “People came to Shenzhen looking for work. At Foxconn, you would see literally hundreds of people at the gate. Wanting to get in to try and get a job.”

Foxconn also had a fleet of buses that would drive out to villages – sometimes up to 500 miles away — and pick up workers keen to get higher-paying jobs in the city. “It was a way to get out of the fields,” O’Very said. “That bus would show up three days later with 60 people on it and ready to work… You’d see them and they’d have a bag the size of an attaché case and a set of clothes and that’s all they had. And you know Foxconn would provide for them. They would stack four people in a room that was eight-by-ten with two sets of bunk beds and a little chest of drawers on the side. They would make their money and send it home.”

For the first time, the sheer number of employees Foxconn was taking on meant that it hired Chinese employees to carry out mid-level management jobs: something previously limited only to Taiwanese nationals. It also diversified its manufacturing production lines and the specialization of its labor force.

By the early 2000s, Foxconn was a giant. Through a series of mergers and acquisitions and the expansion of its factories all across China, it was among the leading manufacturers in the country. In 2001, Hon Hai became Taiwan’s largest private-sector company in terms of sales, with sales rising 55 percent to $4.5 billion, while profits rose 26 percent to $382 million. That year, switched its manufacture of Intel-branded motherboards from Asus over to Foxconn. In 2002, Bloomberg hailed Gou as the “king of outsourcing.” In November 2007, Foxconn announced plans to build a new $500 million plant in Huizhou, Southern China. The following December, 2008, Foxconn’s global sale revenues reached $61.8 billion, which was even higher than two of its highest-profile clients, Dell and Nokia. The aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, which saw a return on the part of consumer demand for consumer electronics products, saw Foxconn’s fortunes improve. In the 2011 Global 500 listing of the world’s biggest corporations, published on July 25, 2011, Foxconn leaped to 60th position, from its previous 112th place.

Vertical integration

Right from the start, one of Terry Gou’s strokes of genius has been his push toward vertical integration, meaning one firm combining two or more stages of production normally operated by separate companies. In this way, it is similar to Apple. Apple has long championed a vertical model by controlling both hardware and software on as many levels as possible. For example, the iPhone runs iOS software designed by Apple, which is optimized through the mobile processors that run it, which Apple also designs. “Despite the benefits of specialization, it can make sense to have everything under one roof,” Wharton management professor David Hsu has said.

In the case of Foxconn, vertical integration meant producing its own materials and ensuring its production lines ran as efficiently as possible. When Max Fang, former head of procurement for Dell in Asia, visited one of Foxconn’s factories, he reported of Terry Gou:

“He had this vision and the guts to do anything in a big way,” Fang recalled. “When I first visited the factory, I saw the whole value chain nicely and effectively designed, starting from a big coil of sheet metal at one end that was cut, formed, welded, and stamped to make the top and bottom of the chassis. Then they did the in-line subassembly, adding the floppy drive, the power supply, and cables. It was all shipped to customers who only had to install the motherboard, CPU, memory, and hard drive. After this revolution by Gou, final computer assembly was easy.”

As Foxconn has expanded, it has continued to push for as much control as possible. It does this through both mergers and acquisitions, and also strategic partnerships. By manufacturing as many parts as possible in-house, Foxconn has been able to shorten its downstream supply chain to an impressive degree. Quoted in the New York Times on July 6, 2010, Foxconn spokesman Arthur Huang said that: “We either outsource the components manufacturing to other suppliers, or we can research and manufacture our own components. We even have contracts with mines which are located near our factories.”

Foxconn’s ability to produce products quickly and flexibly has helped it steal smartphone orders from Chinese manufacturers ZTE (Zhongxing Telecommunication Equipment Corporation) and Huawei Technologies. It has also competed for desktop, laptop and tablet orders with specialized Taiwanese manufacturers including Quanta Computer, Compal Electronics, and Wistron.

In addition, it pushes to enter new markets constantly. Its flexibility, cutting edge technology and wide product portfolio has allowed it to win orders from brands including Samsung Electronics, Hewlett- Packard (HP), Sony, Apple, Microsoft, Dell, and Nokia.

City campuses

Foxconn’s factories are almost unimaginable in scale to many in the West. They are enormous complexes, complete with sleeping quarters, restaurants, hospitals, supermarkets and swimming pools packed into, in the case of Foxconn’s Shenzhen factory, a 2.3 square kilometer space. They are more like factory towns or, as CNN once described it, a “heavily secure” university campus. The university analogy may sound more pleasant than the reality of working in a giant factory actually is, but it’s not incorrect.

O’Very, the Foxconn manager who worked at the plant in the late 1990s and early 2000s, said he saw the campus explode in just a few years from about 45,000 workers to more than 250,000. He recalled looking out of his hotel window and seeing a new factory being built in less than two weeks. “There’s a field that was next to us and there was nothing there. Literally within a week they had built a building three-stories high. It took them probably about 11 days to build it. And they literally had hundreds of workers. I mean just 24 hours a day working on this thing. All four walls going up at the same time… It was amazing… And the day they finished they were already bringing in people and start the training because as soon as those lights turned on they had people in there.”

Foxconn’s factories are typically staffed — at least on the factory floor — of 18 to 25 year olds from rural parts of China. Many are away from their home villages, friends and family for the first time. They sleep together in large dormitories, eat meals together in the Foxconn cafeteria, and work alongside one another on the production line. There are even mass entertainments put on by management from time to time.

In August 2011, the company staged an event at its Longhua factory campus in Shenzhen, where 300,000 employees lived and worked. It included a parade, including Alice in Wonderland floats, people playing vuvuzelas, and employees dressed as “Victorian ladies, geishas, cheerleaders, and Spider-Men.” After this was a two-hour rally inside a giant sports stadium featuring acrobats, musical performances, fireworks, and speeches, in which employees were told to “care for each other to build a wonderful future” and “treasure your life” (this wording is important, given that it came after the spate of Foxconn suicides.)

Despite this, leisure facilities are generally inadequate for the scale of the factories. One CNN report noted that, for a staff of more than 300,000 at its Shenzhen factory, there were just five swimming pools and 400 computers available for leisure use.

Foxconn gets a manufacturing education

In the early days, Foxconn was inefficient and poorly organized. Nothing was optimized or designed for maximum productivity. Products were made in batches, which oftentimes lead to delays when parts ran short or if certain assembly operations took longer than others. Workers performed several assembly operations and collecting parts themselves if they ran low at their stations. It was less like an efficient factory, and more like a cottage industry.

“Everything was done by hand and it wasn’t optimized,” said O’Very. “It was scattered… It wasn’t flowing. It didn’t have this flow to it until they started to figure out how to get this continuous flow.”

An American, O’Very was initially hired to be the face of Foxconn to its American clients, particularly Dell, which was one of it’s biggest customers at the time. O’Very was a trained industrial engineer, and helped the plant’s production lines become more efficient. He had studied the works of W. Edwards Demming, the manufacturing efficiency guru.

To his surprise, the Foxconn managers talked a lot about Henry Ford. Foxconn’s assembly lines were laid out much like Fords’ Model T assembly lines, which had become obsolete almost seventy years before. He was surprised. As an organization, Foxconn seemed completely ignorant of several decades of modern manufacturing theory and practice.

But in in the six years he was there, Foxconn leaned very quickly how to adopt modern factory practices and make their operations more efficient, O’Very said. In just a few years, Foxconn’s managers learned and applied the theory of continuous flow manufacturing, which aims to keep the production process continually flowing. Sometimes called repetitive-flow manufacturing, there is no waiting for assembly operations to be performed or parts to be delivered to shop-floor workstations. The products move down the line is a continuous flow, making it very fast and efficient. It’s harder to achieve than it sounds, and requires the study and optimization of every step of the production process. The entire operation has to be tightly integrated, and any potential delays ironed out.

“In six years they went a Henry Ford kind of model T production line — like Charlie Chaplin — to something much more efficient,” O’Very said.

As they worked to improve efficiency, partially assembled products would be moved down the line on trolleys on rails that would get passed from one worker to the next. Then the lines were motorized. The trolleys would be pulled along the assembly line on a chain drive. Manual screwdrivers were replaced with faster and more efficient pneumatic drivers. Later on, AI-driven vision systems were added to keep an eye on the assembly process and automatically stop the line if mistakes were spotted. “They reproduced the whole American history of industry over 70 years in just six years,” said O’Very. “Their learning curve was steep and they embraced it.”

Preorder Tim Cook book

Leander Kahney’s new book about Apple’s CEO will be released on April 16, but you can preorder it from Amazon today. “If you’re interested in a great overview of Tim’s still-ongoing tenure at Apple, Leander Kahney’s latest book is exactly what you need …. I highly recommend it.” — Paul ThurrottWork Culture

The work culture at Foxconn was very demanding. Foxconn had a very militaristic culture. Orders were given form the top and expected to be followed to the letter. There was no tolerance for mistakes or inefficiency. The hours were long and punishing. Shifts were typically 12-to-14 hours long. Sometimes, O’Very would start work at 6am and work all the way through the day until 10PM at night.

On his first day, he got a taste of Foxconn’s militaristic culture: “I come around the corner, and there’s three platoon-sized groups. They’re in a military formation. And they’re barking at these guys like literally like they’re recruits. I was in the military for nine years. It was like I was back in the army.”

The new recruits were marched into the factory and told to stand behind workers on the production lines. They stood there for two days watching the workers perform their tasks.

“Their work for the first two days is just standing there at parade rest watching what they will start doing three days from now,” O’Very said. “Twelve hours a day. Literally eight to 12 hours a day, they stood there watching what their job is going to be.”

After two days, the new recruits took the place of the workers they had been shadowing, who in turn, were moved to a different part of the factory. There, the workers spent a couple of days patiently watching other workers that they would soon be replacing.

The tasks on the production line were usually mind-numbingly specific. Workers would often be required to insert and tighten one or two tiny screws, before passing it to the next worker, who would inset and tighten a different tiny screw. The products would be assembled one tiny screw at a time as it passed down a long line of workers working quickly and efficiently.

“Each little screw would be put in by literally a different person and it would go to the next stage and the next stage and the next stage,” O’Very said. “We had these elaborate 50, 60, 70-station manufacturing processes for you know literally just putting in two screws and the next person would put in two screws and that was their job.”

There was no tolerance for mistakes or slip-ups. If a worker made a mistake, they would be reprimanded publicly in front of the other workers. If the worker made the same mistake twice, they would be fired.

The hours were long. Shifts were often 12 or 14 hours long, and workers would toil six days a week, sometimes seven days a week if there was the need. “It was brutal, brutal hours,” O’Very said. “ I mean, they took it easy on me and I was working 75, 80 hours a week when I was there… All that you hear was true. They worked them.”

Life was tough for the line workers, but in many ways was even tougher for the managers. O’Very frequently saw managers getting reprimanded for mistakes made on the line or if the line fell short on its quotas. The managers wouldn’t be reprimanded in front of the line workers, but in front of the other managers at daily production meetings. One of O’Very’s colleagues, who had worked for Foxconn for 25 years, was suspended for a week when his team failed to meet their quota. There had been a delay in the delivery of some parts and his part of the operation got a late start. He was suspended for a week without pay. His position was taken by a deputy – the “guy who watched him do his job,” in O’Very’s words. “They had the lines of succession set up. You mess up, they have the next guy waiting.” The reprimanded manager was only allowed to return because of his long history at the company, and an almost spotless work record.

On another occasion, O’Very was in a meeting when Terry Gau walked in. He “slams the door and he says, ‘who are we going to put out of business today?’ First words out of his mouth. ‘Who are we putting out of business today?’ and nobody said anything. So he points at one of the VP’s and says get out of here you’re done.”

The VP was fired because he didn’t have a plan. Gau then turned to the vice president’s boss and said he should be ashamed because he didn’t prepare him.

He was made him stand in the corner like a naughty child. “He stood there for the entirety of the meeting with his face in the corner,” said O’Very. “This is a grown man but he’s not going to say ‘boo’ because if he did he loses that job he won’t find work anywhere else… it was literally, you’ll never work in this town again.”

Occasionally, the senior managers would visit a local massage parlour at the end of a shift. The other mangers would be obliged to tag along. “You’re working from 6:00 in the morning until 9:00 o’clock at night and then there’s this expectation that if the big boss decides he wants to go to one of the massage houses, all of the minions have to follow him. And you all have to sit there while he’s enjoying his two hours at the massage house with the girls and the cigars and whatever else. Until he’s done. And then once he’s done then everybody can go home.”

The group of 10 or 15 managers would sit and play cards, or sing karaoke, until the big boss was ready to go home. “You sit around and the girls would come out and sit there with you there would be karaoke or whatever but no one’s really having a good time. A couple people are. But generally you’re there because he’s there.”

After six years, including a stint working for Foxconn in the United States, O’Very quit, mostly because of the lack of promotion opportunities and the harsh work culture.

“It wasn’t a whole lot of fun,” he said. “There was a glass ceiling if you weren’t Chinese. You weren’t moving up. And that’s ultimately why I left. And I just did not like the way they treat other folks. I had a lot of people that I have a lot of respect for and really liked and I just didn’t like the way they were being treated. The whole office that I was with is gone. Every one of them quit. They said they have had enough.”

The hours and workload aren’t much better for Apple’s workers either.

Gautam Baksi, a former Apple product design engineer, said the constant traveling to China and the long hours at the factory caused him to eventually quit.

“I spent an enormous amount of time in China along the way. You spend enormous amount of time with people along the way, night after night on a product. You get to know a lot of stuff.

“This is why I left Apple after five years there,” he said. “I did 30 trips to China in my five years there. Almost all in the Guangdog region. I pretty much almost got a divorce. I wouldn’t have a kid if I had stayed at Apple. The hours were awful. 20-hour days were common. I found myself waking up in hotel rooms at 5AM clothed, with my computer on my lap because I was doing cold calls or answering email and that happened routinely. The few nights I would get off in China, I got obliteratingly drunk. Because I needed to let go off a lot of steam. I didn’t like what I saw in China at all. Shenzhen, in Foxconn specifically. There’s a lot of moral issues that we can talk about separately that I found with that. But being there was both an honor and a privilege. I would have paid money to be an Apple PD. Then when you get there, after awhile you’re maybe like, this isn’t exactly what I wanted to do. It’s a personal sacrifice. And I know a ton of guys who are still there. I constantly ask them. ‘How do you manage this?’ The cachet of being at Apple is a huge one. It opens every door that I’ve been in since then. I wouldn’t be here at Google if I didn’t work at Apple. So the trade-offs are really good. Financially the trade-offs are good. And if you do a good job, you are treated well.”

Suicides

Foxconn is secretive, but in a way that’s very different to Apple. Terry Gou knows that his clients don’t want the world to know where their iPhones or Dell PCs or Sony PlayStations are made, and does his best to stay low profile, despite Foxconn’s enormous footprint. This meant that, when it suddenly became a globally recognized name in 2010, it wasn’t ready. The incident that caused its rude arrival in the spotlight was a series of suicides at Foxconn’s factories.

One death took place in 2007 and another in 2009, but it was 2010 when there was a sudden massive upsurge, with an estimated 18 employees attempting suicide and a minimum of 14 deaths. The first of these took place in January 2010, when a young factory worker named Ma Xiangqian jumped to his death. Xiangqian had recently been demoted to cleaning toilets after accidentally breaking some factory equipment. He had been working triple the legal overtime limit. “Life is hard for us workers,” said his sister, Ma Liqun, shortly following Xiangqian’s death. “It’s like they’re training us to be machines.”

Terry Gou’s initial attitude to the suicides was not one that found favor, particularly among members of the press in the West. His own attitude to a work-life balance was not entirely, well, balanced. Gou’s mantras included sayings like, “work itself is a type of joy,” “a harsh environment is a good thing,” and “hungry people have especially clear minds.” He also failed to take into consideration the mental impact that it might cause to many workers, coming from small communities to work in giant factory complex — often under very strict conditions. Rules in place were designed to forbid managers from treating their underlings harshly, but there were nonetheless complaints that this was not followed.

“I should be honest with you,” Gou told one reporter, concerning the suicides. “The first one, second one, and third one, I did not see this as a serious problem. We had around 800,000 employees, and here [in Longhua] we are about 2.1 square kilometers. At the moment, I’m feeling guilty. But at that moment, I didn’t think I should be taking full responsibility.” After the fifth suicide, he said that, “I decided to do something different.” However, it was not until the ninth Foxconn employee had leaped to his death, that Foxconn took the step of erecting more than 3 million square meters of yellow-mesh netting around its buildings to catch jumpers. It also increased wages for the factory workers in Shenzhen by 30 percent to 1,200 renminbi ($176) per month, and promised a second raise six months later. It also set up a 24-hour counselling center staffed by 100 trained workers and opened a special stress room where workers could dish out their frustrations on mannequins using baseball bats. The firm also hired the New York PR firm Burson-Marsteller to help devise its first ever formal public-relations strategy. Such a thing had never been required before.

“We’re asking ourselves the same question [about suicides],” said company spokesman, Liu Kun. “Foxconn has never seen anything like this before in the past 20 years of operating on the mainland. We’ve checked the work records and couldn’t find any direct link between the working conditions and the suicides.” A few people pointed out that the number of suicides was actually below China’s average rate of 14 per 100,000, according to the World Health Organization. However, this attitude did little to quell concern.

The Foxconn suicides story was quickly linked to Apple. Although Apple was not the only large company which used Foxconn, it was the biggest and most well known. It also seemed to contrast most strongly with Apple’s progressive image. As the authors of the book Becoming Steve Jobs, which paints Apple and Jobs in a fairly positive light, write:

“How could a company with Apple’s cherubic marketing glow make its devices in Foxconn factories where the drudgery and difficult working conditions resulted in more than a dozen assembly-line workers committing suicide?”

Steve Jobs was probably the wrong person to speak up on the subject. Jobs himself was not adverse to promoting a tough work environment. When he defended Foxconn shortly after the suicide news was reported, he said its factories were actually “pretty nice” and defended it as, “not a sweatshop.” The line which came over worst, however, was his comment that, “We’re all over this,” which struck many people as uncaring.

It also transpired that Sun Dan-yong, a 25 year old who died in July 2009 after throwing himself from an apartment building, did so after losing an iPhone prototype in his possession. Prior to death, he claimed he was beaten and his residence searched by Foxconn employees.

Nonetheless, Apple did make changes. After the suicide reports, it organized a task force to deal with the situation, and put measures into place to try and prevent the same thing from happening. In the years since, Apple has worked to improve its supply chain, although it has still received occasional criticism from labor rights activists and other organizations.

Luke Dormehl and Killian Bell

![Apple and Foxconn, a history [Cook book outtakes] Foxconn workers spell company's name](https://www.cultofmac.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Foxconn-banner.jpg)