Michigan State University baseball coach Danny Litwhiler was reading the campus newspaper one day in 1974 when he decided to call the cops on some of his pitchers.

An article and photo of campus police showing off the department’s new radar gun to catch speeders caught Litwhiler’s eye and he wanted police to swing by the ballpark with the new toy to see if it could read the speed of a pitched baseball.

An article and photo of campus police showing off the department’s new radar gun to catch speeders caught Litwhiler’s eye and he wanted police to swing by the ballpark with the new toy to see if it could read the speed of a pitched baseball.

Litwhiler – a flawless defensive player in the bigs who evolved into a beloved college coach – changed the game of baseball that day. No longer would myth and mystery surround the fastball. Pitchers, for better or worse, would be scouted and evaluated based on a new number – miles per hour.

Photo: Apple

Go to any high school, college or Major League Baseball game and it is not uncommon to see scouts behind home plate with radar guns aimed toward the mound. These days, you may even see a few iPhones thanks to two apps in the iTunes store that measure the speed of pitches (Baseball Radar and Baseball Pitch Speed).

But before we could even get to the point of clocking pitches with an iPhone, Litwhiler had two problems to solve with the speed gun.

The first was battery power. The police happily visited a practice but because the gun was plugged into the cigarette lighter, the officer had to drive his car on the field. Positioned behind the mound, the gun read only about 75 percent of the pitches, but when a number registered, it seem accurate, according to Litwhiler’s account in his autobiography, Living the Baseball Dream.

Photo: MSU Athletics

Litwhiler and the officer figured out the second problem: the gun was not calibrated to read small objects.

Litwhiler contacted the company that made the guns, explained what he was doing and within eight days, had a battery-operated prototype of the kind of guns scouts use today.

“I called Bowie Kuhn, the commissioner of baseball and told him what I discovered about the radar gun,” Litwhiler wrote. “I told him I didn’t want any one team to have the gun, but rather I wanted every professional and amateur team to have the same opportunity to use it. Bowie was pleased to hear about the radar gun, and he said he would notify all professional teams about it. In about a week, I began getting telephone calls, telegrams and letters requesting more information about the gun.”

There are two types of radar guns used in baseball, one that measures the speed as the ball leaves the pitcher’s grip and one that records the speed of the pitch as it nears the catcher’s glove. A pitch tends to slow down as it nears the plate.

Before the radar gun, a fastball was evaluated by the sound it made when it popped in the catcher’s mitt and the wind it generated as the batter swung with futility.

Attempts to apply an actual measurement of speed to a pitched baseball dates back to the games early flamethrowers, like Walter Johnson. In 1917, the hard-throwing Senators pitcher threw baseballs at a munitions laboratory that recorded his fastball at 134 feet per second, or just over 91 miles per hour.

The fastball of the great Bob Feller, who spent his Hall of Fame career with the Cleveland Indians, from the late 1930s through the 50s, underwent similar tests. By sight, players, coaches and former players could see how hard he threw and speculated he may have had the all-time fastest pitch.

Throwing through army ordinance equipment, Feller’s fastball was clocked at just over 98 miles per hour. In another test, he pitted his fastball against a police officer racing on a motorcycle. The thrown baseball beat the officer through the target and by modern accounts, the pitch traveled at more than 100 miles per hour.

Footage of both tests on Feller is below.

One of the most legendary fastball figures was an Orioles prospect named Steve Dalkowski, who was plagued by control problems and alcoholism, according to the Tim Wendel book High Heat: The Secret History of the Fastball. He never made it to a major league game. Dalkowski was the type of pitcher who could strike out 18 batters and lose 6-4 because he walked just as many. In 1958, he had a pitched clocked at 93 mph at a military installation. He had pitched the day before and had to throw for 40 minutes before the equipment could register the speed of his pitch. Those who ever caught him or batted against him would say he threw well past the magic number of 100.

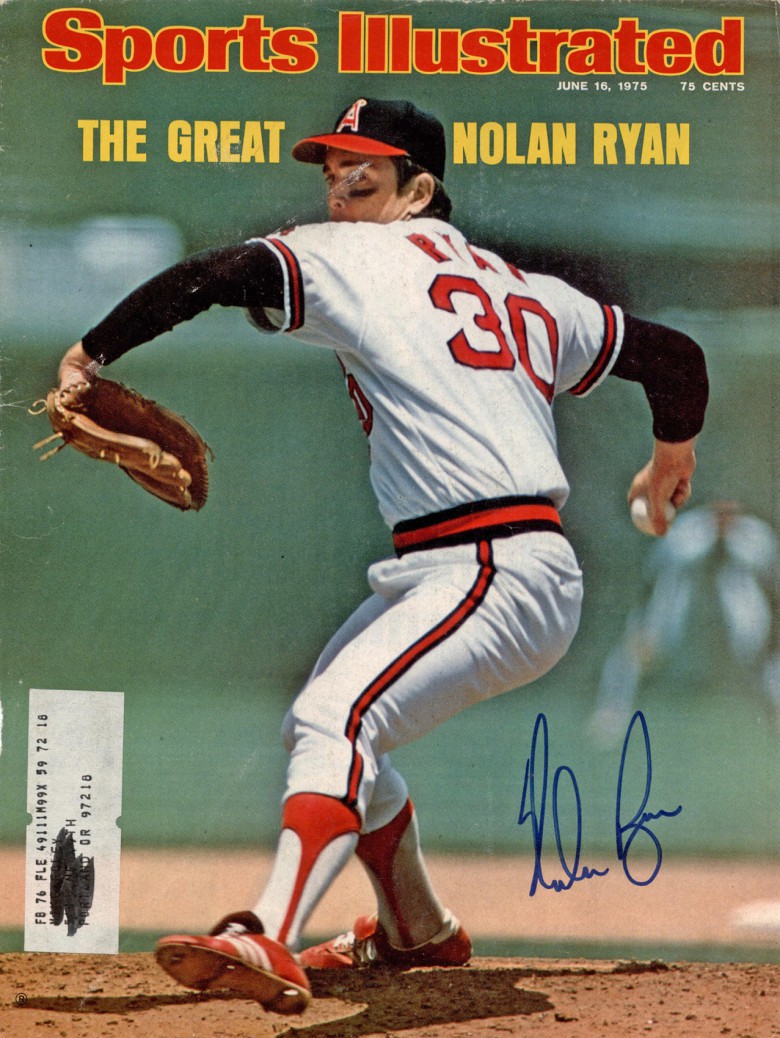

Photo: Ebay

Radar equipment used by Rockwell International scientists recorded a Nolan Ryan fastball in 1974 at 100 mph, a speeded recorded when the ball was about 10 feet away from the plate. By today’s standards, with speeds recorded from 50 feet away from the plate, that Ryan fastball could have been going as high as 108 mph considering how much a pitch slows down as it nears its target.

In the modern era, every pitch’s speed is recorded and the number of pitchers who have thrown at 100 or more miles per hour is a relatively small number.

Photo: Sports Break/YouTube

In the radar gun era, Reds closer Aroldis Chapman, his nickname the Cuban Missile, threw a fastball in 2010 that was clocked at just over 105 miles per hour.

Is he the fastest ever?

Major League Baseball and the Elias Sports Bureau, Stats Inc. do not recognize radar speeds as an official statistic. This probably is to retain some mystery and wonder and keep the debate in bars and ballparks alive.