This week saw the publishing of one of the iPhone’s most recognizable patents.

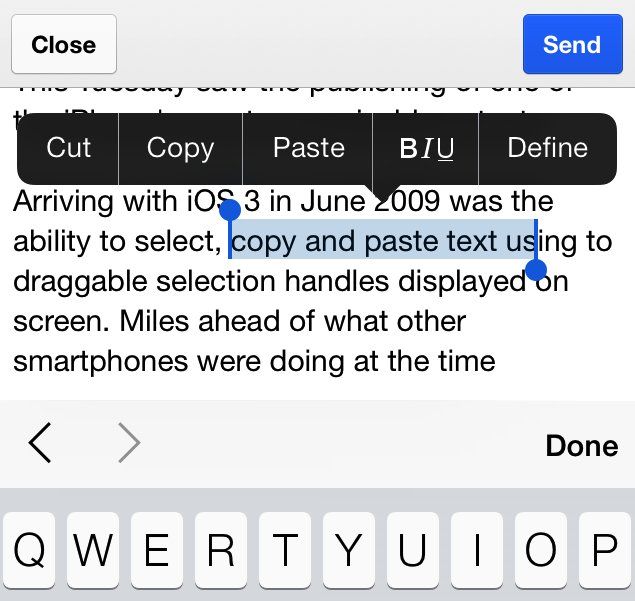

Arriving with iOS 3 in June 2009 was the ability to select, copy, and paste text using two draggable selection handles displayed on screen. Miles ahead of what other smartphones were offering at the time, Apple’s solution was a neat way of transferring to mobile a tool that was a key part of the personal computer user experience.

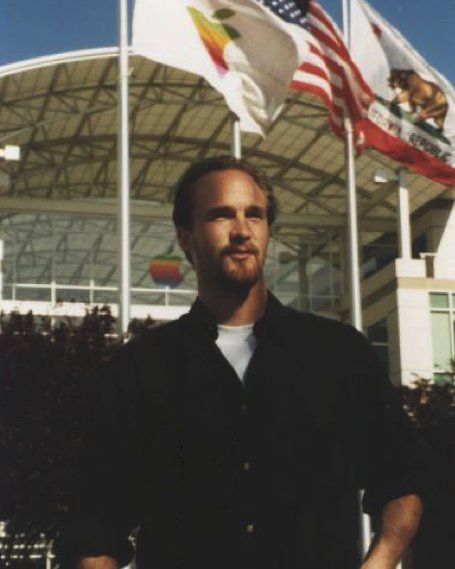

To celebrate the publishing of this historic patent, Cult of Mac spoke with one of its inventors, user interface designer Bas Ording, about the development process.

Ording — who left Apple last year after 15 years with the company — worked on multiple versions of the iPhone from the first generation model onwards. Other than the text selection patent, his main contributions included the look and feel of the iPhone’s pre-iOS 7 virtual keyboard, and the device’s scrolling functionality — including the recognizable “bounce” effect seen when you reach the bottom of a page.

Ording explains that by the time iOS 3 rolled around, everyone working on it knew that text selection had to be included as a feature. The only question was how best to implement it. Apple’s MessagePad devices in the 1990s had translated cut-and-paste to a mobile device by using a stylus, but Steve Jobs was so set against this as an option that the iPhone team never considered it as a solution.

“That was strictly a no-go area,” Ording says. “I remember Steve telling us that if you needed a stylus to use the iPhone he wouldn’t ship it. The idea was always to use your finger instead of other tools.”

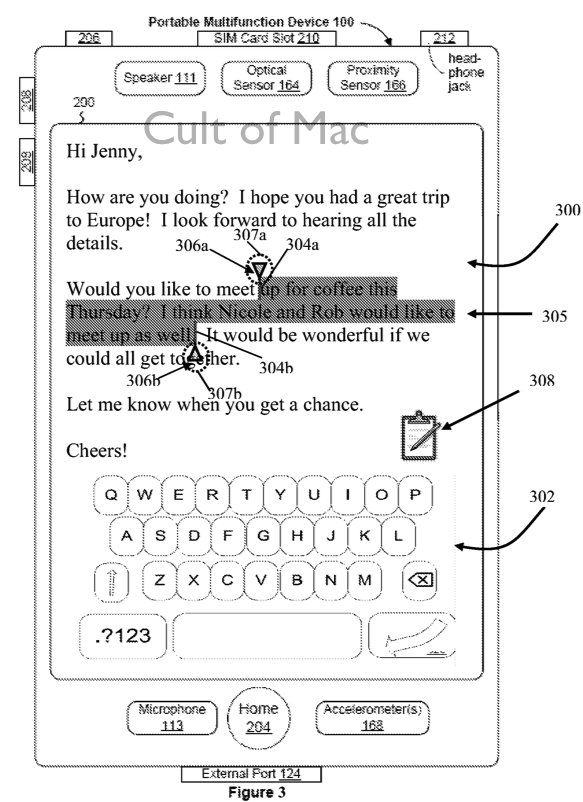

“The idea that we struck upon was having handles at the beginning and end of the text selection that the user would be able to move around,” Ording continues. “Some people called them ‘lollypop sticks’ and we played around with a bunch of different ideas [regarding] how best to do them. It started out with much larger visible handles. We ended up making them smaller and smaller, until they were just dots. You see, it turns out your fingers are actually pretty precise. If there’s a grain of sand on your desk, you can easily target it despite it being a tiny dot. On-screen the dots are small, but in software the invisible active area is much larger, so they’re easy to grab.”

Interestingly, Ording says that he carried out much of his trial work on iPhone text selection using a much larger screen device — essentially a prototype iPad, three years ahead of launch.

“It’s a mechanism that can work on various-size screens, but [the] small screen iPhone was the focus,” he says.

Steve Jobs’ push for perfection was as much on display in the iPhone’s text selection tools as anywhere else, Ording says.

“Steve was very hands-on,” he recalls. “Generally we’d have meetings with him every other week, and [then] much more frequently depending on the phase of the project. We would show him demos of how things were working — and that included text selection. He was very particular when it came to the color of the selection bars, and the appearance of the little shadows we used for the interface. He was very [opinionated] about questions like whether you’d activate text selection with a double-tap or press-and-hold, for example.”

Although it’s not something that Apple can take credit for, the concept of text selection and cut-and-paste is one that is deeply ingrained in the company’s DNA. The first version of cut-copy-and-paste was created at Xerox PARC in the 1970s by a computer scientist named Larry Tesler — who also invented editable dialog boxes and the Smalltalk browser. When Steve Jobs visited PARC in 1979, cut-and-paste was one of the concepts that was shown to him, and it was one which later found its way onto Apple computers via the failed Lisa.

“[Steve Jobs] was very particular when it came to the color of the selection bars.”

Larry Tesler wound up at Apple, too, where he rose to the role of VP and stayed under 1997. Tesler’s love of simplicity was responsible for the one-button mouse that became synonymous with the Mac. The legacy of his dislike for computer modes (he often wore a t-shirt reading “Don’t Mode Me In” and his California licence plate read “NO MODES”) can, meanwhile, be seen in the wording of the iPhone text selection patent, which describes the comparable tools available on other smartphones at the time, as requiring:

“… user interfaces [which] often result in complicated key sequences and menu hierarchies that must be memorized by the user.”

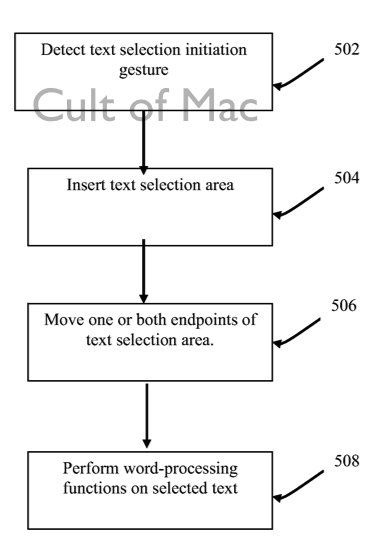

The iPhone, on the other hand, wanted gesture-based text selection to be intuitive. In the words of the patent, Apple stipulated that “detecting a text selection” should be possible using a simple “initiation gesture with the touch screen display” that would then allow “word processing function[s] [to] be performed on the … text located in the text selection area.”

A simplified diagram of Apple’s text selection method for iOS can be seen below:

The “selection of text using gestures” patent was filed March 4, 2008. While it is only one element of the overall iPhone package, everything about its creation — and the overall ethos behind it — perfectly sums up Apple’s approach to design philosophy.

Its claims can be read in full on the U.S. Trademark & Patent Office website.