During the WWDC 2019 keynote, most of Apple’s latest creations drew enthusiastic applause, with one notable exception. The price of Apple’s new Pro Display XDR elicited a somewhat cooler response. But considering just how expensive the monitor is, the fact that it got any applause at all was pretty remarkable.

This is not the first time Apple has had to convince us to pony up for an eye-watering sticker price. Cupertino pulls from a well-established playbook for its keynotes, often employing behavioral science techniques to help soften the blow. (To our brains at least, if not to our wallets).

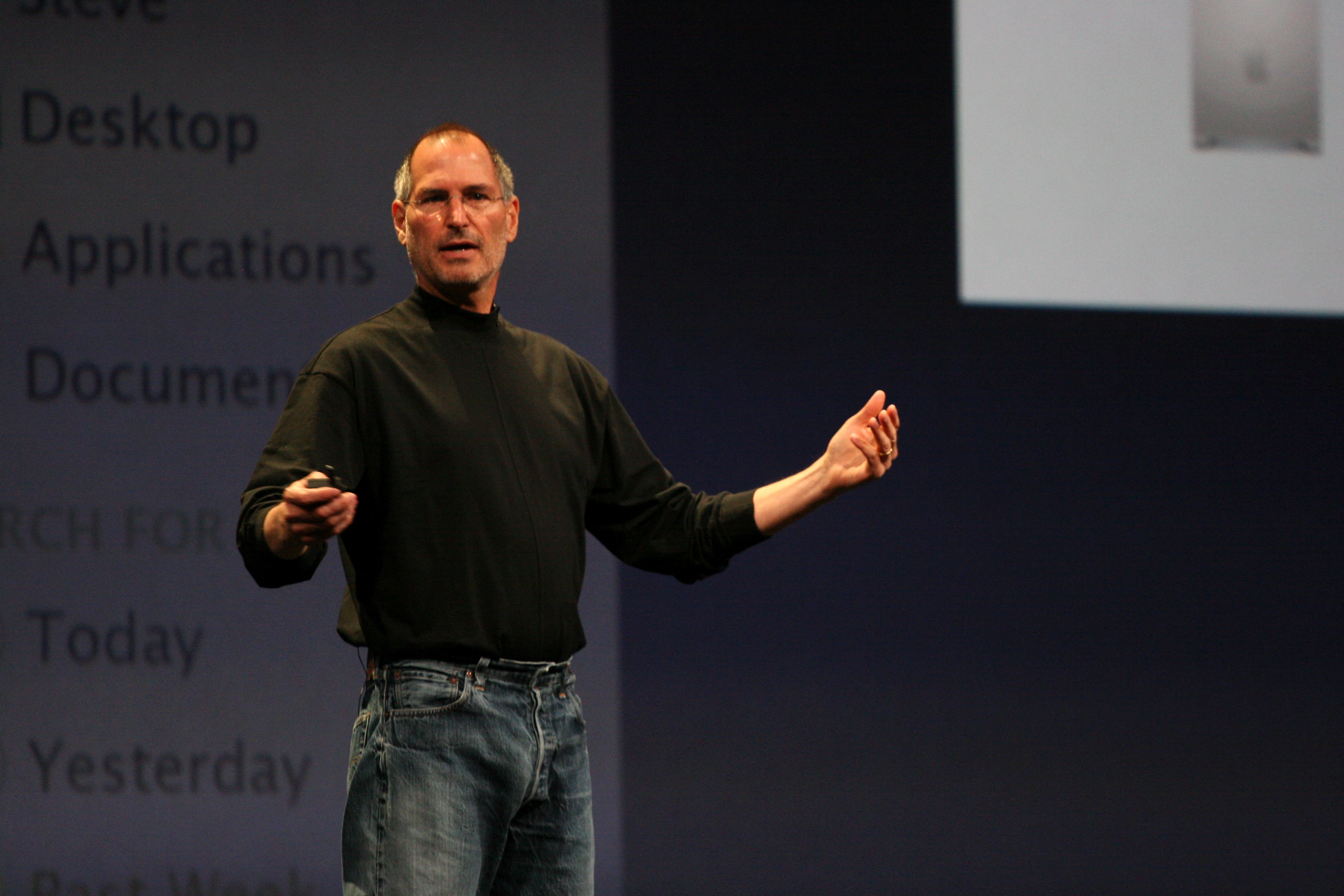

Learning from the keynote master

Steve Jobs was famous for his brilliant presentational skills. His ability to sway audiences and convince them they wanted his products was so legendary that it became known as his “reality distortion field.”

You might say he had it easy. During the golden era of his tenure as Apple’s CEO, he introduced products so awesome that they arguably sold themselves. Who wouldn’t want the original iPod, iPhone or iPad?

But there was one aspect of Apple’s products that was not such an easy sell: the pricing. Apple prides itself on making the best products it can. And that rarely comes cheap.

That is probably why Jobs put so much care and thought into how he presented the price of his products. To this day, Apple executives continue to use the techniques he developed. During last week’s WWDC keynote, that included John Ternus, Apple’s VP of hardware, and Colleen Novielli, from the Mac marketing team.

How Apple anchors our price expectations

Photo: Apple

Before introducing any of the Pro Display XDR’s features, Novielli mentioned a number: $43,000. Seven minutes later, just prior to revealing the actual price, Ternus flashed that same figure up on the screen again.

$43,000 was not the price of the XDR. It was the price of a Sony reference monitor.

Reference monitors are not a product category that Apple has competed in before. By showing us this sky-high price, Novielli and Ternus attempted to manage our expectations. The clear message was that the XDR would not be cheap.

Sure enough, at $4,999, it turned out to be a full five times more expensive than its predecessor, the 27-inch LED Cinema Display.

However, Ternus and Novielli wanted us to think of the Pro Display XDR as 10 times cheaper than its competitors. Whether that is a valid argument remains to be seen. It depends entirely on how comparable the XDR really is to professional reference monitors.

There was more going on here than just a rational argument, however. By showing the number $43,000 several minutes before announcing the price, and then flashing that same number on screen once again immediately prior to the big reveal, Apple appealed to our unconscious minds, using a technique known to behavioral psychologists as the “anchoring effect.”

Photo: Apple

We are all predictably irrational

In the 1970s, two scientists, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, began researching a rather odd pattern in human behavior: We tend to repeat the same mistakes over and over again. In fact, our errors are sometimes so consistent that Tversky and Kahneman discovered they could predict them.

How? Our brains are essentially lazy and try to arrive at decisions as quickly and easily as possible. Rather than carefully thinking every problem through with rigorous Vulcan logic, we often leap to conclusions based upon limited information.

To do this, our brains take shortcuts, substituting difficult problems with easier questions that are quicker to solve with less information. This is not always a bad thing. The ability to think quickly in confusing situations helped our ancient ancestors survive. But thinking in this way to solve today’s first-world problems does not always serve us so well.

These shortcuts our brains use result in biases in our reasoning that we are usually unaware of. And these biases can be used to manipulate our perception of things — like whether the price of Apple’s new display is reasonable.

Think of a number

Even before you knew all the features and benefits of Apple’s new display, you probably had a figure in mind for how much it would cost. We certainly did at Cult of Mac. We even made bets on it as we watched the keynote.

But how were our brains arriving at a figure when we knew so little about it?

That’s where Tversky and Kahneman’s shortcuts come in. One such shortcut is anchoring. In his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman explains that the anchoring effect occurs “when people consider a particular value for an unknown quantity before estimating that quantity … the estimates stay close to the number considered.”

For example, if you were asked whether there were more than 50 countries in Africa, and then asked to guess how many there were exactly, your estimate would likely be higher than if you were originally asked if there were more than 10. It should not make a difference to your answer, but it typically does. Our estimate is drawn to the figure we first considered, hence the metaphor of an anchor.

So when Apple mentions that a similar product costs $43,000, our brains become “primed.” Without consciously realizing it, our estimate of what Apple could reasonably charge us for the display is dragged upward by that anchor.

How Steve Jobs used price anchoring

Photo: Kazuhiro Shiozawa/Flickr CC

Last week was not the first time Apple used anchoring to steer our price expectations. In 2006, when the iPod was in its heyday, Apple launched a product that was very close to Steve Jobs’ heart.

Long before Bluetooth speakers, smart assistants and HomePod, iPod-compatible portable speakers were a burgeoning product category. But Jobs thought they all sucked, and he wanted to make something way better. It was called iPod Hi-Fi.

The trouble was that, at $349, it was considerably more expensive than equivalent products already on the market. So during the keynote launch event, Jobs used an anchor price. He said:

“This Bose product costs over a thousand dollars… And we are delivering audio quality that is absolutely competitive with these products with the new iPod Hi-Fi,” Jobs said. “And we’re going to price it at $349.”

When you’ve been primed by the $1,000 anchor price, $349 does not sound half so bad. It’s only a third of the anchor price, after all. Even though that anchor price was for a high-end audiophile setup, not a portable speaker. And Jobs’ contention that the sound quality was equivalent was just his personal opinion.

Apple uses the same strategy to this day

Fast forward to 2017, when Apple Senior VP Phil Schiller used a notably similar turn of phrase and price point during the HomePod launch:

“Typically Wi-Fi speakers of this quality sell for $300 to $500,” he said. “And a smart speaker may cost you $100 to $200. So it’s not unreasonable for a HomePod to be priced in the range of $400 to $700. So we’re really excited to tell you that HomePod is going to be priced for $349.”

The strategy here is a little different. He throws out so many different prices that it starts to get confusing. But it’s the $400-$700 range that stands out.

Combining the costs of two different products in this way to come up with a higher anchor price is another classic Steve Jobs technique. That’s exactly how he justified the price of the original iPhone, by comparing it to the cost of a smartphone and iPod combined.

Before the HomePod launch, many people expected its price tag to be similar to the Amazon Echo’s: around $120. But by the time Schiller revealed the actual price, our expectations had been anchored higher, once again.

Apple’s attention to detail leaves nothing to chance

By highlighting the way that Apple pitches its prices, I’m not criticizing the prices themselves. While Apple products may be expensive, I believe they usually represent great value for money when you factor in their quality, the user experience, their longevity and their resale value. I suspect that the Pro Display XDR will be no exception.

I’m not even criticizing the use of psychological techniques in Apple’s presentations. It is only right that Cupertino should make the best case it can for its products.

I just find it fascinating to see the attention to detail that the company lavishes on everything — even the way it presents product pricing during keynotes. And how even as Apple has grown so much over these past few years, the company continues to use the playbook devised by Steve Jobs back in the good old days.