This story first appeared in our weekly newsstand publication Cult of Mac Magazine.

Long before Apple’s “Think Different,” ad campaign, before the dot-com boom, before zany became the norm in startup culture, there was Nolan Bushnell, Pong and Atari – the company where Steve Jobs landed his first job.

Bushnell is the godfather of the think different mentality, an unconventional character who ran unconventional companies. He made it a personal mission to attract similarly creative, passionate people to help him to realize some of his ideas, which many people considered wacky at the time.

This post contains affiliate links. Cult of Mac may earn a commission when you use our links to buy items.

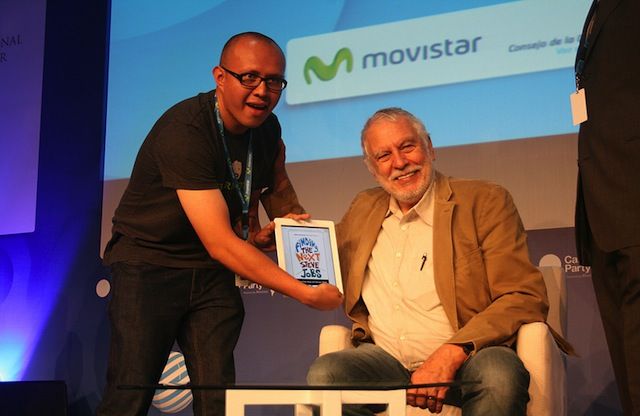

His new book titled “Finding the Next Steve Jobs: How to Find, Keep, and Nurture Talent” aims to give advice on thinking counter-intuitively, taking a chance and hiring ‘crazy,’ and ‘obnoxious’ people, who once on board, should be accommodated.

People like Steve Jobs, who, when he worked for Bushnell had to be placed on the night shift so that he would offend as few people as possible with his unvarnished opinions and patchy personal hygiene. Bushnell’s strategy paid off. When he asked Jobs to help him to design the arcade game Breakout, Jobs and his friend Steve Wozniak designed it in four days.

The success of Atari launched an industry and a new form of a corporate lifestyle. Way before it became a standard part of California corporate culture to hold meetings in hot tubs while on retreats, Bushnell was doing it in the 70s, a time when many engineers still came to the office in suits and ties.

The book was inspired by the anecdotes about Jobs’ short tenure at Atari in Walter Isaacson’s 2011 biography. People kept approaching Bushnell after it came out, asking him to talk about hiring and working with Jobs. So Bushnell, who now heads educational software company BrainRush, responded by capitalizing on that interest. Along with writer Gene Stone, he’s authored a book of notes and tips (broken down into mini-chapters call he calls “Pongs”) on hiring and managing talent in a world that places an increasing premium on creative thinking.

This is an area that Bushnell knows something about. In addition to founding Atari, a company that launched a multi-billion dollar industry, he’s founded other ground-breaking enterprises over a span of four decades that have become cultural touchstones: Chuck E. Cheese, Etak, a car navigation system that paved the way for modern systems, and Catalyst Technologies, one of the first technology company incubators, among others. (He’s also founded some notable flops, including uWink, a chain of interactive entertainment restaurants and Androbot, a personal robotics company.)

What makes this book interesting is that this is the man who started a company that inspired much of what came later and still sets Silicon Valley apart from mainstream business culture. He was also something of a mentor to Jobs, who went on to be called the Edison of our times.

In a recent interview with Cult of Mac, Bushnell recalled that Apple’s co-founder would visit him a couple of times a month over several decades to discuss business, marketing and distribution problems, philosophy, and the technical aspects of usability issues, such as the merits of a computer mouse as a pointing device on a computer screen versus a trackball or a joystick. Jobs obviously decided on the mouse.

“He was always looking for an extension of the mind,” Bushnell said in a phone interview. “He was more focused on tools that would make things easier to use, more intuitive, and felt that a mouse was a superior product for that.”

Acting creatively, so that your company is an advertisement for itself, Bushnell advises, is also part of the strategy. That is partly what attracted Jobs to Atari – its unusual approach to recruiting. According to Isaacson’s biography, Jobs applied for the job at Atari after seeing a “Help Wanted” ad in the San Jose Mercury News that said: “Have fun, make money.”

Bushnell writes that he purposefully packed his company’s lobby with arcade games so that people would have fun while visiting and tell their friends about the experience. What better way is there of marketing a company than by word-of-mouth? He took that recruiting strategy with him as he started other companies too. At Chuck E. Cheese, for example, Bushnell placed help-wanted ads that read: “Work for a rat, earn lots of cheese.”

To be sure, much of the wisdom that Bushnell dispenses is pretty much standard operating procedure for many startups and tech companies in Silicon Valley, yet it’s easy to imagine that many company managers in non-technical industries don’t engage in these practices enough, or not at all.

Also: while these 52 bits of advice have become the norm for many companies in America, they’re definitely foreign in the more bureaucratically-organized and hierarchical companies outside of the United States. One of the biggest complaints of foreigners working in Silicon Valley during the dot-com boom was the flat management structure of startups. Many Europeans just couldn’t get used to that style of doing business. Yet Bushnell and many other startup founders find collecting feedback about both their own ideas, getting new ideas, and finding out about how their products are doing out in the wild essential to success.

Another characteristic of Jobs that fits Bushnell’s hiring criteria is self-motivation and autodidactism.

“I love people who are self-taught, and who have hobbies,” he says. “That is the highest predictor of powerful people.”

Along with Jobs, Bushnell points to computer graphics pioneer Stan Honey as an example. Honey worked as a technical lead at Bushnell’s car navigation company Etak. But in addition to his computer work and his work in television graphics, he’s also a champion sailor.

There are also plenty bits of advice in Bushnell’s book that’s worth being reminded about. For example, number 19: Ask odd questions.

“The questions don’t have to be answerable,” Bushnell writes. “You’re not there to get real answers to real problems. You’re there to witness how a prospective employee’s mind works.”

That is, to see how an individual thinks on their feet, and whether they’re creative about coming up with a solution. This is something that Google has been doing in their job interviews and it’s also something a successful hedge-fund manager friend of mine does when he interviews traders for his fund, asking off-the-wall questions such as “How would you trade if martians landed and took over the earth tomorrow?”

I’m not sure how Steve Jobs hired people, but he definitely would disagree with some of Bushnell’s tactics and “Pongs,”as he calls them in his book. (Pongs are bits of advice rather than strict rules, Bushnell writes. (“One of the ideas Steve and I addressed was the concept of rules. Neither of us felt that creativity could thrive in the presence of strict ones. Thus, the book you’re reading contains no rules. Instead it has Pongs.”)

For example, Bushnell advises his readers that to avoid falling into a rut, they should make long lists of to-do items on their agenda, things from what they really want to do, to things that they’re not quite sure they want to do, that might be a bit offbeat for them. Then they should put numbers against those items and then roll dice, and find out from those roles which item they should take up next.

“What you don’t realize is that because we all tend to make the same choices over and over, we all fall into our private ruts,” he writes. “These ruts do not lead to creativity. Ruts lead to doing the same things, in the same ways, over and over – it’s a vicious cycle.”

When I asked him if he adopts this strategy in making business decisions rather than just personal ones, he replied affirmatively.

“I think that a lot of times we waste time endlessly debating things that are nuanced, such as the color of a web page, or deciding between three logos,” he says. “I did this recently with the Brainrush (his educational software startup) logo. We had three very good, similar ones, and rather than spending any more time on it, I just said, let’s just decide, and we rolled the dice and decided it, and I really like what we ended up with.”

Bushnell admits that this is not an approach that Jobs, a notorious control freak, would likely have adopted. However, when pressed, he simply says that his book isn’t just about hiring passionate, creative people, it’s also about trying to recognize and give creative people within your company room to contribute more.

“Really, the lesson from this book that I hope to make is that, rather than trying to hire more Steve Jobs, try to enable the Steve Jobs who are already working for you, and giving them more latitude to create. That’s really what Google is doing.”

This story first appeared in Cult of Mac Magazine.