The 40-year history of Macintosh computers is a roller coaster of ages golden and dark.

Anything that lasts so long in the forefront of technology has to change to stay relevant. This once-plucky computer that began as an antithesis to the IBM PC, which dominated the world in 1984, is now itself a dominating force, ever pushing the needle in the world of technology.

How did this all happen? Let’s walk through 40 years of Macintosh.

The 40-year history of Macintosh computers

We produced a short video documentary you can sit back and watch if you’d rather do that than read:

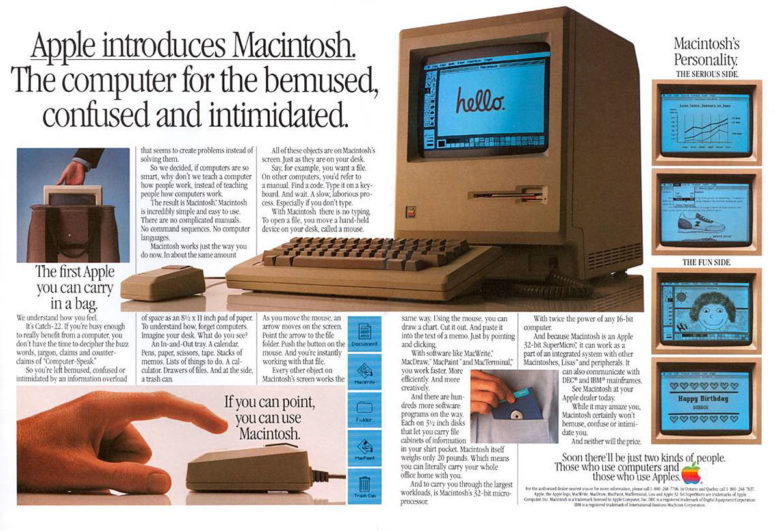

The Macintosh landed in 1984 to a maturing microcomputer market that was starting to consolidate. After less than three years in the microcomputer market with the IBM 5150, Big Blue was sucking the air out of the room. Commodore, a household name, would never have a more successful year.

The diverse world of different platforms and operating systems was rapidly collapsing in favor of PC clones. The machines were easy to manufacture but impossible to use without a crash course in how computers worked.

The industry was begging for a polished, easy-to-use computer that no one aside from Apple could be bothered to invest in building.

Welcome to the Macintosh 128k

Photo: Apple

The Macintosh was a computer, but it wasn’t an unapproachable machine like other computers. It was a desk appliance, just like a telephone or calculator.

All the software on the Mac worked the same way. You pointed and clicked. The app windows had a titlebar with a close button on the left. You could click the scroll bar to move around.

If you ever didn’t know what to do, you could read through the menu bar, always present on the top of the screen. It showed you the keyboard shortcuts, so you could learn those over time.

The fundamental difference is that the familiar Macintosh operating system was always there to guide you in whatever you were doing.

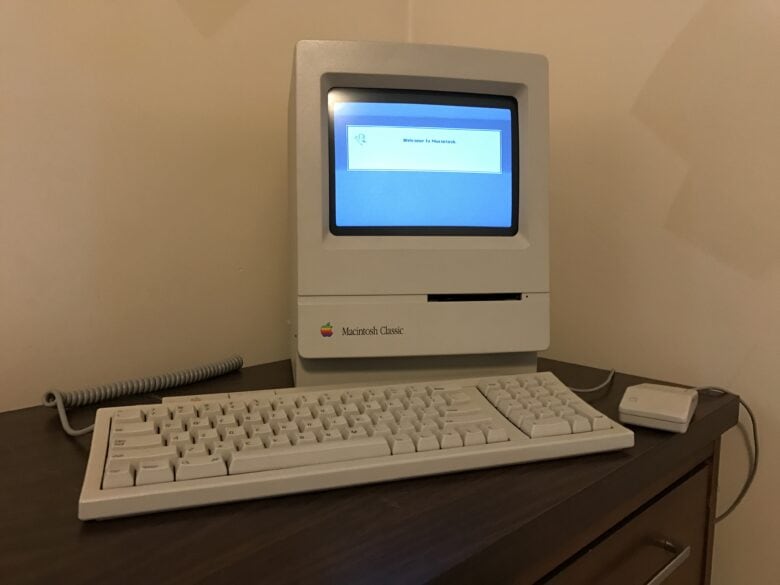

Quirky design

Photo: D. Griffin Jones/Cult of Mac

As a computer, the Macintosh was a bit weird.

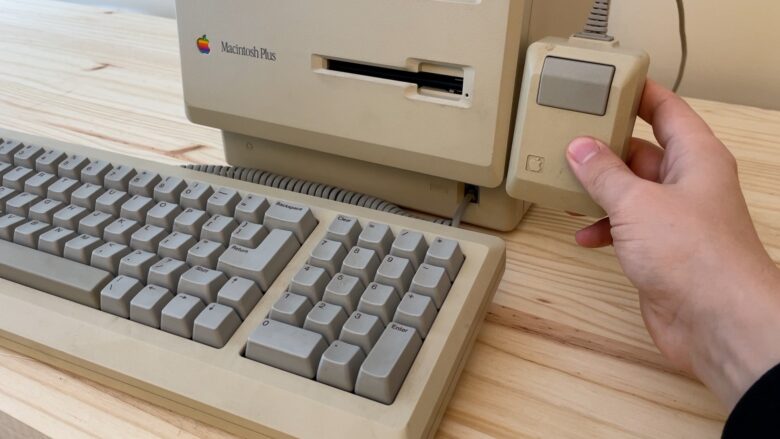

The mouse and keyboard were a bit chunky, but you can see the family resemblance. They’re all designed as one cohesive collection.

Photo: D. Griffin Jones/Cult of Mac

The mouse is actually more comfortable to hold than you’d think — you’re supposed to wrap your hand around it with one finger on the top. Since it’s symmetrical, it’s just as easy to use left-handed as it is right-handed. That design motif stuck over time even as tastes changed.

Photo: D. Griffin Jones/Cult of Mac

Apple co-founder Steve Jobs insisted that the original Macintosh keyboard didn’t have any arrow keys on it, so users would be forced to use the mouse. While arrow keys were added in with the Macintosh Plus, designers still made them as inconvenient to use as possible by arranging the keys in a straight line. They finally gave up in the early 1990s, adopting the modern upside-down-T layout.

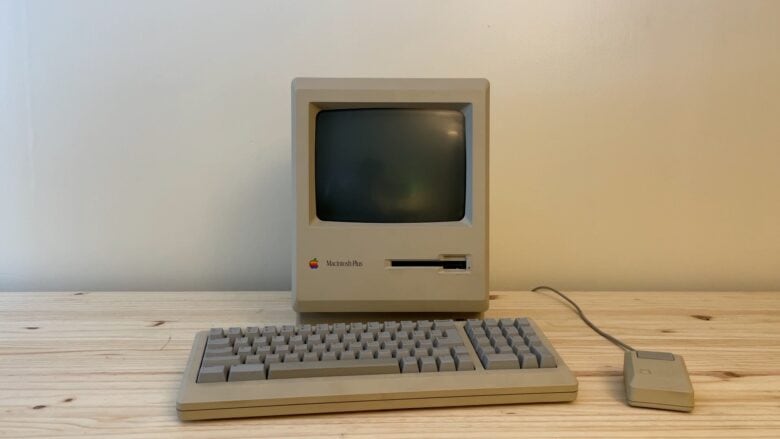

Rapidly updated to the Macintosh Plus

Photo: D. Griffin Jones/Cult of Mac

Revisions of the Macintosh were quickly rushed out the door. Later the same year, the Macintosh 512K quadrupled the amount of memory. Another year later, the Macintosh Plus doubled it again to 1 megabyte — and that could be upgraded to 4 megabytes.

Hard drives were still very expensive, so none of these machines came with any built-in storage. The external secondary floppy disk drive was a popular accessory for mitigating constant switching back and forth between two floppies.

QuarkXPress secures its success

A company called Microsoft — whose biggest claim to fame was the crude operating system that ran on the IBM PC — started to make applications for the Mac, like Word and Excel. Microsoft also made a version that ran in its own graphical environment called Windows, but no one really used that yet.

The Macintosh catalyzed the new field of desktop publishing. Its high-resolution display, its powerful software (Aldus PageMaker and QuarkXPress), and its ease of use made it the perfect fit for newsrooms big and small. Even an expensive computer was a drop in the bucket compared to the price of the $50,000 typesetting machines that preceded it.

More power, more Macs

Photo: Apple

What would an even higher-end Macintosh be like? The Macintosh II.

This monster of a Mac came in a gigantic case with internal space for either two floppy drives or one floppy and one 40MB hard drive, expansion slots that could drive six color monitors, a new processor that was twice as fast and a new line of keyboards and mice.

All of this came at a hefty price tag. The Macintosh II was over double the cost of the Mac Plus, starting at $5,498.

Photo: D. Griffin Jones/Cult of Mac

Its innovations trickled back down over time. The Macintosh SE/30 also had a built-in hard drive, single expansion slot and an even faster processor, but in the familiar all-in-one form factor with the 9-inch black and white display. The Macintosh Classic was a pared-down model that removed the expansion slot and retained the original 68000 processor at the cheapest price yet, only $999.

The first (good) laptop

In the ’80s, a portable computer meant one of two things:

- An all-in-one machine complete with a CRT display and floppy drives, weighing around 25 pounds without an internal battery, with a handle on the back for “convenience.”

- A tiny machine with a footprint no larger than its own keyboard, an LCD matrix display with space for around four lines of text, very little compute power, but some modicum of battery life.

Photo: Apple

Apple briefly attempted to make the best of both worlds: a full-size, desktop-class flat-screen portable computer with the highly imaginative name Macintosh Portable. It was swiftly removed from the market.

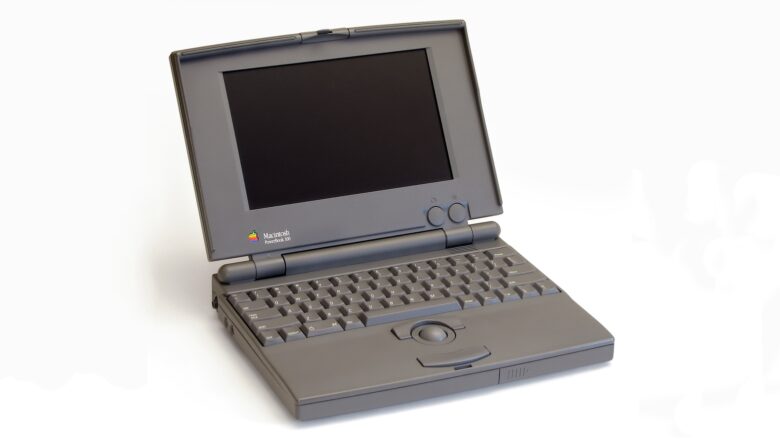

Photo: Danamania/Wikipedia CC

Talk about a glow-up. Just two years later, the PowerBook got the formula right: a hinge in the back that folds like a book, a backlit screen, the pointing device below the keyboard. Compared to modern laptops, the biggest anachronism is its trackball instead of a trackpad.

The PowerBook was a hit product, exactly the right formula at the right time to break into the world of business.

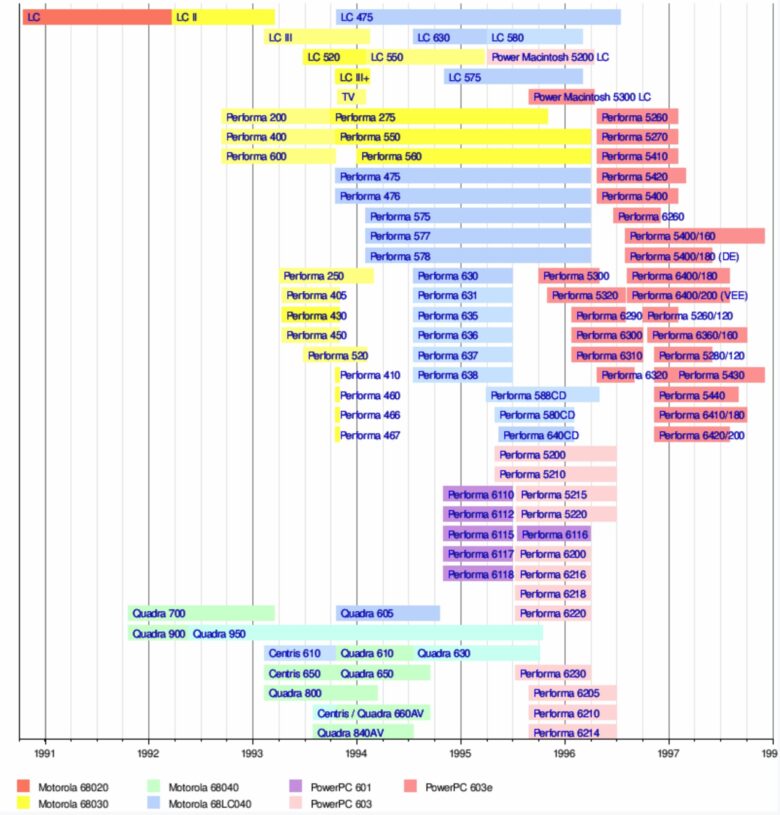

Simply too many Macs

Screenshot: D. Griffin Jones/Cult of Mac

In the ’90s, the Macintosh lineup started to get out of hand.

Apple replaced the all-in-one form factor with a horrible abomination of design, the Macintosh LC 500 series. For reasons that no one to this day can entirely understand, Apple also sold identical machines called the Macintosh Performa 500 series.

At the high end, Macs with the new 68040 chip were called Macintosh Quadra. Except some computers with similar chips were sold in the LC and Performas line, but not the Quadra line.

To end this confusion, Apple introduced a new line of midrange machines called the Centris. Did I say end? No, it actually made it worse. The Macintosh Centris line had the low-cost version of the 68040 and all of its models were also sold under the name Quadra.

Apple then transitioned from the 68k processors to new PowerPC chips, calling these new machines Power Macintosh.

But the numbers and names only got longer. The range now started at the Performa 5200, which was also called the Power Macintosh 5200 LC, which was identical to the Power Macintosh 6200, the same computer in a different case. There were even more layers of confusion when you added the 7000 series, 8000 series and 9000 series computers.

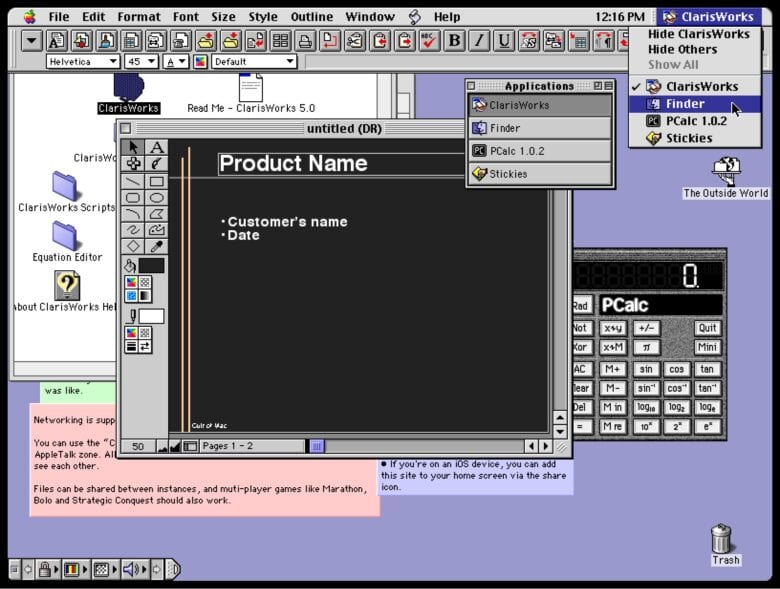

Mac OS 9 showing its age

Screenshot: D. Griffin Jones/Cult of Mac

Unable to put together a modern successor to Mac OS, the operating system was still being held back by the technical limitations of 1984. You could run multiple applications at once, but only the active application could do anything. Everything in the background was frozen.

All the apps shared the same pool of memory. Any app could read or interfere with the memory of any other app. Or the operating system itself. It was shaky and unreliable — and when any one thing crashed, everything crashed.

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, the company was running on fumes. An entirely new Apple Computer company with a different culture, different hardware and different operating system needed to be built from the ground up, simultaneously with keeping the existing products on life support.

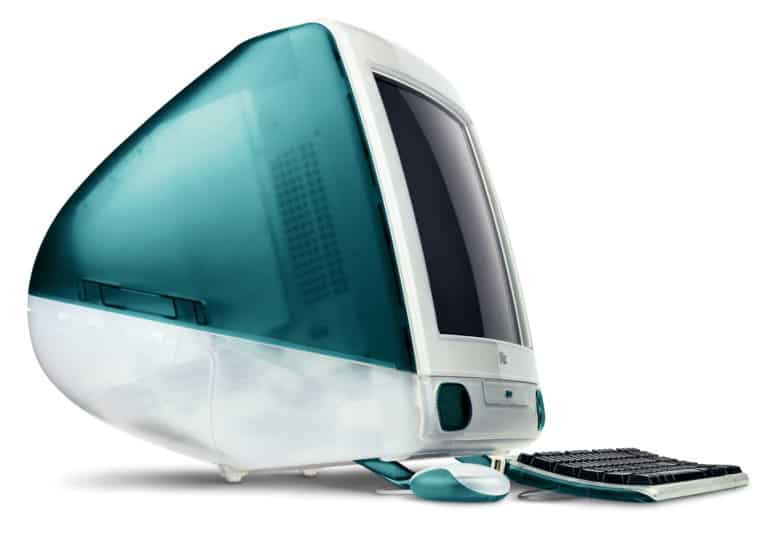

The iMac G3 starts it all over again

Photo: Apple

The pressure was on for Apple’s first big move after its change in management. In just a year and a half, that came in the form of the iMac G3. Suddenly, a computer wasn’t a complicated, more expensive way of playing games or typing letters or balancing checkbooks. Computers were how you used the Internet. And the iMac was the computer you wanted.

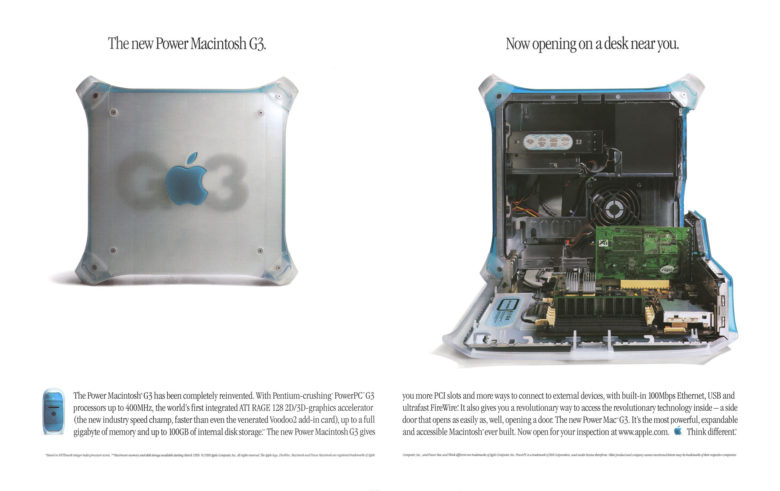

Photo: Apple

Then came the Power Mac G3. It was a tower computer, but just as easy to use — with just as clever a design. You didn’t have to fiddle with screws or metal panels; just flip down the door and you could upgrade the memory or install a PCI card.

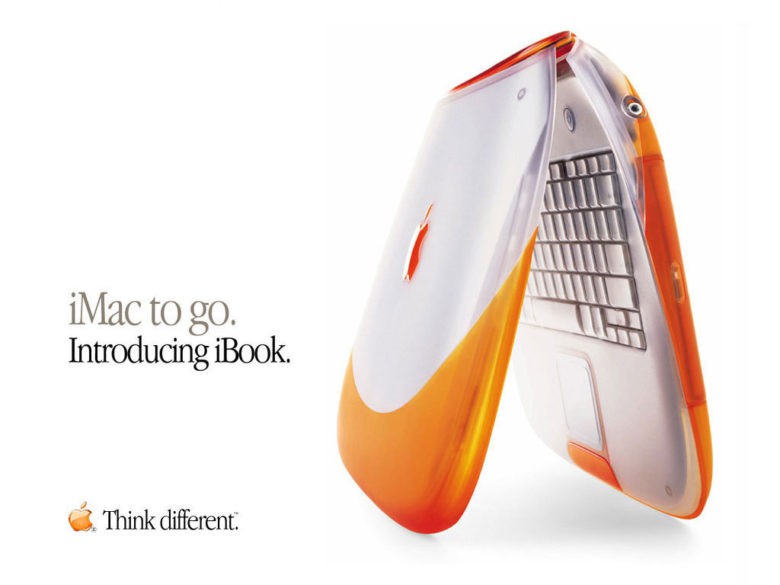

Photo: Apple

Then came the iBook. Using a technology called AirPort (based on some engineering standard called Wi-Fi) you could use the Internet from a laptop without plugging in an Ethernet cable.

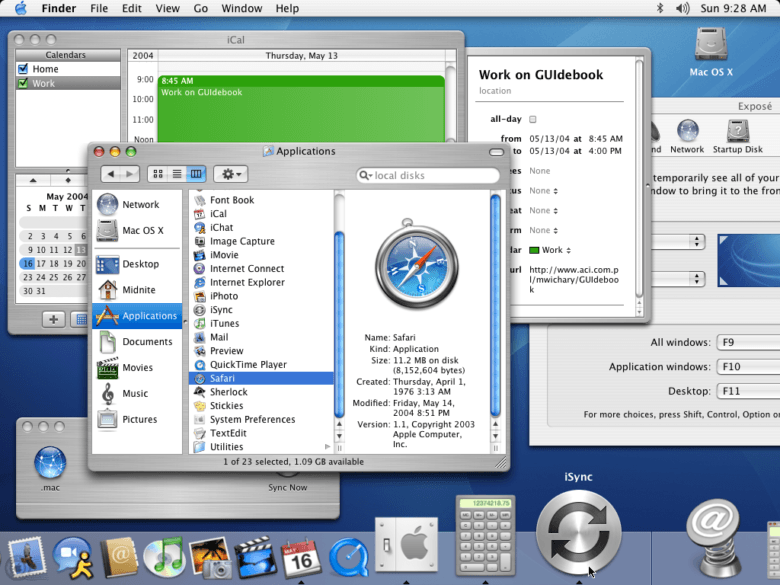

Image: Gudebookgallery/Apple

Leveraging technology from NeXT that Apple had acquired, the next-generation operating system wouldn’t be an evolution built on top of Classic Mac OS anymore. OS X made a clean break. Through a years-long process of previews, announcements and developer betas, Mac OS X 10.0 finally shipped in 2001.

And by now, Apple’s design studio was on a roll, throwing everything at the wall to see what would stick. What if you made a computer shaped like a sunflower? What if everything was brushed metal? What happened if you tried shrinking the Power Mac G4 into an 8-inch cube? What would a rack-mountable server running OS X look like?

Return to function over form

Photo: Ashley Pomeroy/Wikimedia Commons

This couldn’t last forever, though. Apple had made its statement — but now it was time for more practical designs to take over.

The PowerBook made its second big leap, easing into the design that effectively holds to this day: an aluminum makeover, a widescreen 16:10 display, speaker grilles to the left and right of the keyboard, a glass trackpad that would grow over time, and, starting in 2006, a MagSafe connector.

The Power Mac G5 adopted a serious and imposing aluminum case. In a taller and broader tower design, it had ample room for a big power supply and even liquid cooling. The iMac G5 from a year later was able to cram the same chip into a slim all-in-one case.

After that, Apple ran into a serious problem. The PowerPC chips that it used to build its computers were running too hot and demanding too much power.

When it came to updating the Mac mini, PowerBook and iBook, the G5 was simply a lost cause. Designing a low-power machine is always a balancing act between speed, energy consumption and heat. The PowerPC architecture demanded too much energy and ran far too hot to offer any meaningful increase in speed.

With no other path forward, it was time for another wild card.

The Mac moves to Intel

Photo: Apple

Intel was on a roll in the mid-2000s. After the Pentium’s success in the ’90s was beginning to plateau, Intel’s new Core 2 Duo chips were the latest and greatest in the business. In one of the most dramatic moments in Apple keynote history, Steve Jobs revealed that Mac OS X was compiled to run on both PowerPC chips and Intel all along.

And with the Mac running on Intel just a year later, every computer got a radical makeover.

Laptops in 2008 were generally about an inch thick and weighed about 5 pounds — even Apple’s own MacBook. Until the MacBook Air arrived in 2008. So thin it fit inside a manila envelope, laptops would never be the same. And the MacBook Air never would have been possible on PowerPC processors.

The MacBook and MacBook Pro were themselves refreshed with a slimmer “unibody” design. This changed the design from dozens of stamped metal pieces and frames into one machined shell with a lid and a bottom plate.

The iMac was redressed in aluminum, and in 2012 got a similar, radically thin redesign.

New products take Apple to new highs … and the Mac to new lows

Photo: Apple

In just 10 years, Apple would go on to launch four transformative products, none of which had anything to do with the Mac — iPhone, iPad, Apple Watch and AirPods. Apple’s stock ballooned tenfold, making Cupertino the most valuable publicly traded company in the world.

Meanwhile, Apple forgot how to make keyboards and pro desktop computers, and Intel forgot how to make better processors. Speculation has it that at one point, the executive plan was to develop the iPad into the modular computer of the future and let the Mac coast into retirement as a legacy platform.

The Mac is back, and back-er than ever

Photo: Apple

But thankfully, the tide changed, driven by Apple silicon. What happens if you do spin up an ARM chip into a desktop-class processor? You get something incredible.

Laptops with unimaginable battery life. Computers that just don’t quit. iMacs so thin, you have to put the headphone jack on the bottom.

With the arrival of Apple silicon, the Mac has learned how to coexist with the rest of the product lineup.

With the M-series chips inside every Mac sharing an architecture with the A-series chips inside every iPhone, and the iPad bridging the gap between the two, the Mac is stronger than ever.

On the software side, even as the world pushes toward lowest-common-denominator web apps, truly native Mac apps are making a comeback. Swift and SwiftUI are the latest technologies to rapidly build software interfaces faster and easier than ever before. And for the first time ever, the same codebase can build an app for iPhone, iPad and Mac alike.

So much technology is shared between these platforms that you might think that Apple is just years away from merging them all into one. I don’t think that’s true. If anything, the history of Macintosh computers proves that Apple is all about using their common foundation to strengthen them all.