A few days ago, we learned about the iPhone’s shutter, the part of the camera that “opens and closes” to let light onto the sensor. Today, we’re taking an in-depth look at the aperture, aka hole. The aperture is an opening in the lens that can be made bigger or smaller. Like shutter speed, its primary purpose is to control how much light reacts with camera the sensor (or film).

Also like shutter speed, aperture has some extra effects on how the image looks. Specifically, it can control how much of the image, front to back, looks sharp.

What is a camera aperture

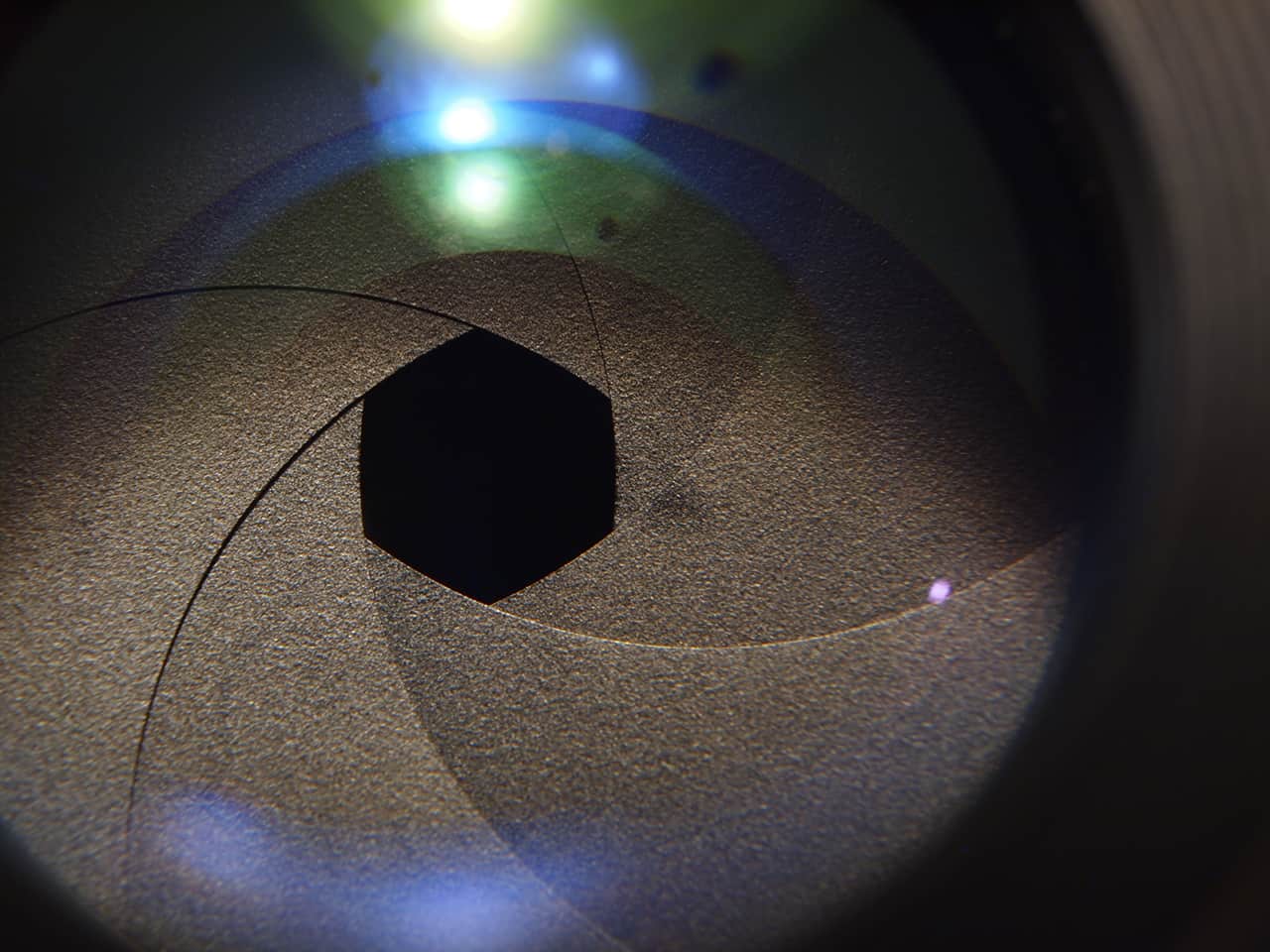

The aperture is a diaphragm inside the lens, the size of which can be adjusted. Just like the iris in the eye, a bigger hole lets in more light, and a smaller hole lets in less. The most common aperture design uses five or more blades arranged like in the image below. As these blades shift together, the size of the hole changes.

Photo: Calgary Reviews/Flickr CC

Some old cameras have interchangeable metal sheets with different-sized holes punched into them. These sheets are moved behind the lens to control light levels.

How aperture affects your image

Photo: Charlie Sorrel/Cult of Mac

As we saw, a camera’s shutter can be used to control how sharp or blurred a moving object will appear in your photos. Changing the aperture can have an even bigger visual effect on the image, because it controls how much of the picture is sharp. That’s because, when reduced in size, a hole turns into a lens, and can focus the light coming through it.

Here’s an example you can try at home: the pinhole camera, or camera obscura. On a sunny day, cover the windows in a room to make the room as dark as possible. Now, punch a tiny hole in the cover. On the wall opposite the window you’ll see an image, upside down and back to front. This image will be a copy of the scene outside your window.

If the image is too dim, or you don’t see one at all, try making the hole a little bigger. This will let in more light. But be careful. As you increase the size of the hole, the image on the wall will blur more and more. That’s why your regular window-size window doesn’t project an image on the wall.

If you put a sheet of photographic film or paper inside a box, then punch a tiny pinhole in the other end of the box, it works the exact same way, only you can actually record an image.

So you see, while a larger aperture (or hole) lets in more light, it also makes the image more blurred. An actual camera uses a lens to focus the incoming light. But the size of the aperture still affects the sharpness of the picture.

Depth of field

Photo: Charlie Sorrel/Cult of Mac

When your camera focuses its lens on a subject, a certain amount of the image is also sharp in front of and behind this plane of focus. The amount of sharpness is called the “depth of field.” (It might help to use the popular term “depth of focus” to make this clearer.)

The amount of depth of field is partly controlled by the size of the aperture. So, when the aperture is small, like the pinhole in our window blind, the image is sharp from the horizon in the far distance right up to the objects nearby. This looks good in a landscape shot, where you want everything sharp.

Photo: Charlie Sorrel/Cult of Mac

Conversely, when the aperture is wide open, like our regular open window, the aperture contributes almost nothing to the sharpness of the image. The subject that the lens is focused on — perhaps a person’s face — will be in focus. However, the background will be blurred (as will anything between the persona and the camera). This is “shallow” depth of field. It is highly desirable in a photo, because you can blur a distracting background, and focus on the subject.

If that was the whole story, we’d be golden. The iPhone would be able to take those great portrait shots, with the subject popping against a soft background. Unfortunately, that’s not the whole story.

Sensor size, lenses, the iPhone and Portrait Mode

Photo: Ste Smith/ Cult of Mac

Among other things, depth of field is also affected1 by the size of the sensor, the distance from the back of the lens to the sensor, and the kind of lens itself. Like all smartphone cameras, the iPhone’s camera is just too cramped to get the space it needs for a proper shallow depth of field.

That’s why it fakes it, with Portrait Mode, explained in this great how-to. The iPhones 8 and X use a depth-sensing camera to work out where the background is, then uses a filter to blur it. It’s a clever trick, and one that can work well.

Unfortunately, there’s no other way around the iPhone’s inability to achieve a shallow depth of field. If you focus the camera on something very close to the lens, anything far away will blur out. But that’s about the best you can achieve.

This may be why the iPhone aperture is not available for manual control. While you can adjust the shutter speed, white balance, and even ISO (sensor gain, or sensitivity), manual camera apps can’t adjust the aperture. And to be honest, it wouldn’t make much difference if you could.

Conclusion: The aperture is really important

To sum up, then: Aperture control is just about the most important control on a camera, from a pictorial point of view. It is also the only control not available manually on the iPhone. But — and this is a big but — the iPhone’s Portrait Mode looks like it will eventually be good enough to compensate for this shortcoming.

If you have a regular camera, set it to “aperture priority” auto mode, where you choose the aperture, and the camera adjusts everything else to fit. If you prefer an iPhone, then you’ll just have to wait until you get one that is up to the task. But at least now you know what you’re missing.

- Technically, this subject is a lot more complex. A lot of depth of field is about the perception of sharpness, and the relationships between various factors that are too complex to go into here.Let’s just say that, if you’re going to write in and explain that we should have been more accurate with terminology, or talked about circles of confusion, then don’t. This guide isn’t for you. It’s meant to make the principles of aperture and depth of field clear to non-experts. ↩