With his open letter defending Apple’s Irish tax strategy, Tim Cook positions his company as a sledgehammer-tossing freedom fighter at battle with Big Brother-style EU bureaucracy.

But unlike Cook’s previous missives on LGBT rights and the importance of privacy, this open letter seems unlikely to be met with near-unanimous support. While railing against the EU’s massive assessment of €13 billion euros in back taxes owed by Apple, Cook ignores the facts of the matter — and seems tone-deaf about painting the world’s biggest company as an underdog.

Apple is in Ireland for tax reasons, not to save local economy

Cook begins his open letter, titled “A Message to the Apple Community in Europe,” by talking about Apple’s contribution to European economies, being the largest taxpayer in Ireland, the largest taxpayer in the United States and ultimately the largest taxpayer in the world. (Which, as one of the world’s highest-grossing companies, makes perfect sense.)

He also describes Apple’s arrival in the Irish city of Cork in 1980, which came at a time when the area was “suffering from high unemployment and extremely low economic investment.”

Apple, Cook writes, was able to see past the lack of investment and think different about what a place it saw as having the potential to be a great overseas headquarters for the Cupertino company. Today, Apple employs around 6,000 people in the area — heartwarmingly including “some of the very first employees,” Cook says.

The reality is somewhat less about Apple’s rebel yell freeing gray-suited drones from a life of drudgery. In fact, as an Apple tax adviser noted in a 1990 meeting while discussing the country’s taxation in the region: Apple’s “profit is derived from three sources — technology, marketing and manufacturing. Only the manufacturing element relates to the Irish branch.”

In other words, manufacturing was the part that could most easily be replaced if Apple didn’t get a great tax deal.

Apple’s long “tax holiday”

Apple’s arrival in Ireland came at the tail end of a golden age of tax sheltering in the country. From 1956 until 1980 (the year Apple arrived there), foreign companies were wooed with to in Ireland with an astonishing interest rate of zero. Apple ultimately enjoyed a “tax holiday” until 1990, when the company had to renegotiate its deal — albeit to terms that remained incredibly favorable.

The crux of Cook’s open letter essentially feels like a straw man argument.

“Over the years, we received guidance from Irish tax authorities on how to comply correctly with Irish tax law,” Cook writes, saying that this same guidance is available to any company doing business in Ireland. “In Ireland and in every country where we operate, Apple follows the law and we pay all the taxes we owe.”

The question, of course, is not whether Apple pays the tax bill it’s presented with — but how this bill has been calculated. According to the European Commission probe, Apple paid a tax rate of as little as 0.005 percent on its European profits in 2014. To put that number in perspective, it’s around $50 tax for every $1 million brought in.

Cook also frames the EU as a vindictive bureaucracy targeting both Apple and Ireland. “The European Commission has launched an effort to rewrite Apple’s history in Europe, ignore Ireland’s tax laws and upend the international tax system in the process,” he writes.

The discrepancy between what Apple pays and what smaller companies must pay is the big story here — not the way Cook frames it, as plucky underdogs Apple and Ireland against the monstrous European Commission. EU member states are compelled by law to follow approved taxation laws. Turning this into a story about Ireland’s place in the EU is … well, sleight of hand on a grand level.

The fake “head office”

This type of slick business maneuver seems well-practiced by Apple’s accountants. The EU report on Apple’s Irish tax setup notes various dealings that emphasize the labyrinthine nature of Apple’s tax structure, which is built around two separate business entities — Apple Sales International and Apple Operations Europe.

For example:

“The Commission’s investigation has shown that the tax rulings issued by Ireland endorsed an artificial internal allocation of profits within Apple Sales International and Apple Operations Europe, which has no factual or economic justification. As a result of the tax rulings, most sales profits of Apple Sales International were allocated to its “head office” when this “head office” had no operating capacity to handle and manage the distribution business, or any other substantive business for that matter.

Only the Irish branch of Apple Sales International had the capacity to generate any income from trading, i.e. from the distribution of Apple products. Therefore, the sales profits of Apple Sales International should have been recorded with the Irish branch and taxed there.”

Cook seems to acknowledge this when he writes that, “A company’s profits should be taxed in the country where the value is created. Apple, Ireland and the United States all agree on this principle.”

The argument he lays out is that Apple’s R&D takes place predominantly in the United States, “so the vast majority of our profits are taxed in the United States.”

The problem is that none of this explains Apple’s vast overseas cash pile, which currently stands at around $200 billion. Or, indeed, the aforementioned “Apple Sales International” loophole.

The $200 billion elephant in the room

Ultimately, Cook’s doing what any good CEO would do: standing up for his company. Like the never-ending Samsung lawsuit, this tax battle is not likely to be over anytime soon.

Unfortunately, this is one battle I can’t see Apple winning.

As a publicly traded company, Apple’s obligated to do whatever it can to make a profit, whether that means some seemingly dodgy tax-avoidance practices or not. But unlike many of Apple’s previous battles — most recently, the iPhone-hacking standoff with the FBI — it’s tough to frame the Cupertino giant as a righteous underdog this time around. Or as a company that’s likely to win favor with the public over its stance.

Apple’s high-profile tax situation has the potential to be for Tim Cook what the environmental criticisms and Foxconn controversy became for Steve Jobs.

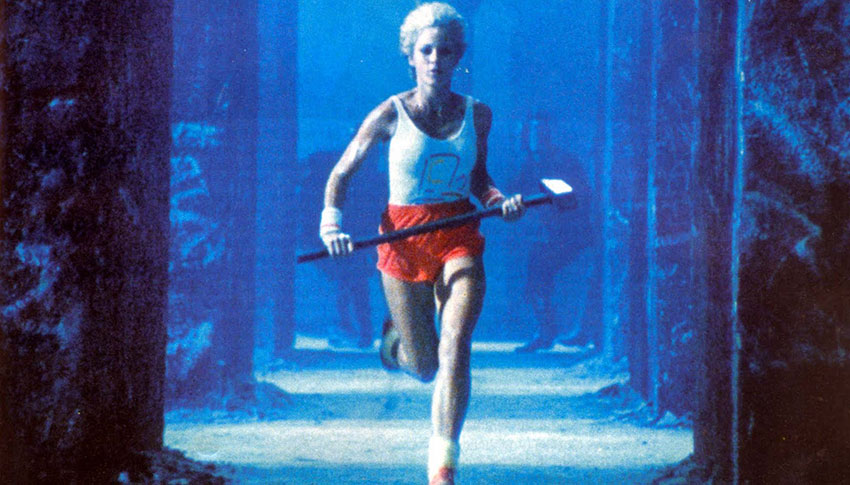

It’s going to be a bitter slog for Cupertino to emerge from, although no doubt it will. But it’s pretty far from the scene set in Apple’s renegade 1984 commercial.