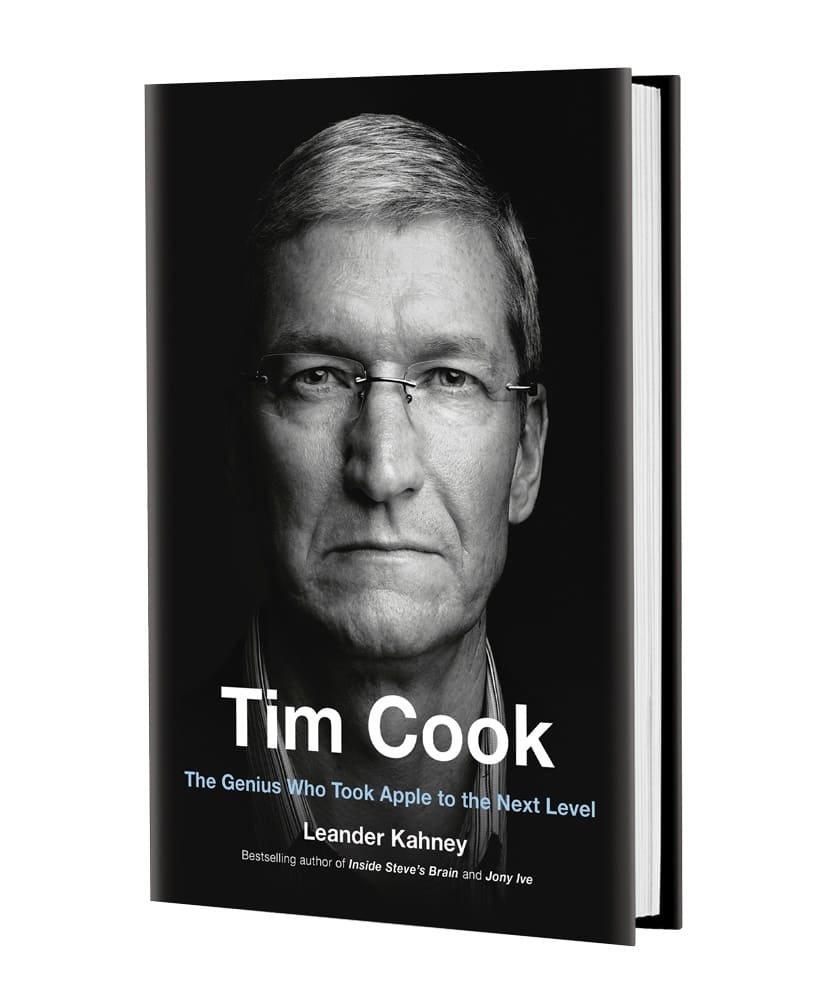

This post was going to be part of my new book, Tim Cook: The Genius Who Took Apple to the Next Level, but was cut for length or continuity. Over the next week or so, we will be publishing several more sections that were cut, focusing mostly on geeky details of Apple’s manufacturing operations.

This post was going to be part of my new book, Tim Cook: The Genius Who Took Apple to the Next Level, but was cut for length or continuity. Over the next week or so, we will be publishing several more sections that were cut, focusing mostly on geeky details of Apple’s manufacturing operations.

As iPhone growth exploded, Apple struggled to keep up with demand. Every year, the number of iPhones sold would double, which meant that Apple kept adding new suppliers and assembly operations to keep up. It was a monumental struggle.

How the Operations Department operates back at Apple HQ

Helen Wang was a Global Supply Manager in Apple’s global supply chain group, a group of about 30 staffers who managed the supply of components for all of Apple’s products. The group would meet a couple of times a week, and the most important meeting was the weekly “clear-to-build” meeting. Jeff Williams, the V.P. of operations at the time, usually hosted the meeting.

In front of everyone is a big spreadsheet with certain items are marked in red. These are the “gating items,” the items that are in short supply and likely to hold up production unless the shortage is addressed. The gating items are listed according to importance, or rather urgency, with the number one gating item the one lost likely to interrupt production. There is competition among the global supply managers not to the in charge of any gating item, especially the number one.

That week, all 30 managers were gathered for the Friday morning meeting and the number one gating item belonged to Wang, who now runs her own supply chain consultancy. There was a problem with the iPhone’s vibrator, a small but important module that vibrates when the phone rings, or there’s an alert or an alarm. Usually, the managers know ahead of time what items are in short supply, but in that particular occasion, the report that there would be a vibrator shortage was delivered just before the meeting.

Williams asked the group, “who manages this vibrator?” and someone mentioned Helen’s name. “So I was sitting in that room and I was like ‘yeah I’m here’” she said. “And I was so stressed because I was like, oh my gosh, I just got to know this morning and I did not have the time to dig into this. I actually don’t know. I did not know. I felt bad. I’m not afraid of problems, but I feel bad. I did not grasp what’s going on there, but yet the numbers showed that it was a terrible number. It shouldn’t be that. So I was just like, ‘OK, what am I going to do now?’”

Preorder Tim Cook book

Leander Kahney’s new book about Apple’s CEO will be released on April 16, but you can preorder it from Amazon today. “If you’re interested in a great overview of Tim’s still-ongoing tenure at Apple, Leander Kahney’s latest book is exactly what you need …. I highly recommend it.” — Paul ThurrottWang might have been freaking out, but Williams was unphased. Wang was one of the best managers in the group, with a reputation for being dogged, conscientious and hard working. She knew how to solve supply chain problems and was consistently creative. According to Wang, Williams told the meeting: “Oh Helen. I know her and I know she’s going to solve it. So let’s move on, talk about the next problem.”

After the meeting, Wang set to work immediately, calling the vibrator supplier, which was based in Japan. There was a technical problem with one of the machines in the plant. It was discovered Friday Japanese time (which is 16 hours head of California time) and reported to Apple just before the meeting as a potential issue that might halt production. The plant had been trying to solve the problem, but hadn’t been able to tackle it.

Wang spent Friday calling the plant every couple of hours trying to understand the problem, but also offering help and advice. If the supplier needed it, Wang could marshal Apple’s huge resources to help tackle the issue. Eventually, she dispatched a team of Apple’s engineers who were based in Japan, who spent the weekend working with the Japanese supplier to fix the faulty machine. Wang kept calling every couple of hours all through the weekend to get progress reports, which she wrote up in daily emails that she sent to her manager and Jeff Williams. “Of course I didn’t report to him every hour but I knew he cared about this problem,” she said. By Monday, the problem was solved and production resumed.

William’s demeanor and Wang’s response was typical of the operations under Cook’s influence. Cook’s values trickled down. Like Cook, Williams trusted his staff and delegated responsibility. Although Apple can be a very top-down organization, staffers are expected to take solve problems in their domains. They are empowered. They are also expected to work hard, be proactive, pay attention to every detail, and solve problems. Wang said although she was young (she was in her early 30s at the time), she felt grateful that Apple’s management trusted her – and other staffers – to tackle issues without being micromanaged.

“The senior director level empowers their people,” she said. “You always feel like, even if you’re young, you might be junior.. that whatever the role you are, you feel like you are making decisions in the best interest of the company, and the company trusts you. This is how Tim and Jeff lead, how much trust they put on you.”

Structure of Operations

There’s no single operations department at Apple. Rather, operations is an umbrella term for a range of different groups that handle manufacturing, distribution and service. The biggest group is perhaps the supply chain team, a cross-functional organization that’s responsible for managing Apple’s vast contract manufacturing operation. Within this group are lots of smaller groups responsible for different aspects of the production process.

There’s a design for manufacturing team, which makes sure proposed products can be manufactured at scale. It includes manufacturing engineers, process engineers and quality engineers, among others. There’s a yield team, which is responsible for maintaining the quality of products or components coming off assembly lines.

To ensure that supply meets demand, there’s a planning department that forecasts projected sales and helps figure out – in extreme detail – all the resources needed to meet its projections, from the tonnage of recycled paper for packaging to the number of camera modules for a big iPhone launch.

Forecasting works hand-in-hand with the Global Supply Management group, sometimes known as procurement, which arranges the supply of source materials and components. There are GSM staffers, for example, for all the major components of Apple’s products. One GSM staffer might be in charge of all the memory components that go into the iPhone, iPad and Macs, while another oversees hard drives across the product line. When she was a GSM, Wang was in charge of interconnects – the cables and connectors that connected components inside the iPhone, iPad, iMac and other Apple products.

There’s a large team that works on distribution and delivery. This group is responsible for how components coming from all over the world are delivered to assembly plants for final construction. They also coordinate delivery of finished products to Apple’s stores worldwide, as well as third-party warehouses.

There’s Apple Care, Apple’s vast service organization, which is also part of operations and takes care of repair and servicing of products after they are sold. Apple Care is a big, sprawling, worldwide operation that runs repair centers around the world, including Apple’s own stores, and several big call centers.

All these departments work together and coordinate, even at the earliest stages of product development. Jony Ive’s industrial design group, which is responsible for the primary development of new products, gets input from the design for manufacturing group, which ensures that proposed products can be made at a mass scale. Apple Care offers input to ensure that the product can be repaired by the Apple store geniuses.

Operations is perhaps the largest part of Apple’s operation, but it’s difficult to estimate the size of operations. Apple doesn’t publish an org chart – internally or externally. One ex-operations staffer estimated that operations might be as big as 30,000 or 40,000 people, which constitutes the vast majority of the 50,000 workers that Apple has based in and around Cupertino. The staffer said when she was at the company in the late 2000s, the iPhone procurement team grew from a couple of hundred people to a couple thousand people now. “It’s just huge,” she said.

MPMs and GSMs

In Apple’s supply chain group, there are two basic types of managers: Global Supply Managers (GMS) and Materials Program Managers (MPM).

The Materials Program Managers are in charge of particular products at Apple. There are MPMs for each model of the iPhone; another for the HomePod speaker, another for the AppleTV, and so.

The GSMs are commodity specific – not product specific. They manage a commodity like hard drives or memory chips, which go into a variety of products.

The MPM is more like a product manager – they are in charge of a particular product – whereas the GSM is in charge of the components that go into a product, or several products.

MPMs are responsible with supplies of components and costs in the supply chain. They are part of a product development team, and are responsible for procuring the necessary materials for the production of a product in a financially sustainable fashion, and to meet the product’s target cost goals, and to work on forecasting cost reduction plans. The MPM us works closely with the finance organization, negotiating pricing and strategic planning of the supply chain. They also work closely with the manufacturing contractors, which is often the final system assembly house. Foxconn is one of them, for example.

“The MPM analyses the projected demand,” said Wang. “Demand coming from the planner or coming from the sales forecast, and then you go through the supply, which is the material supply, which is the report is going to tell you. So you managed to contract manufacture, make sure the material readiness. To support the production requirement, which is going to support the sales forecast.”

“The GSM is responsible for outside supplier qualification and auditing of subcontracted facilities to ensure the quality of the operations is up to the expectations of their employer, and that their product (which could be assembled parts, components or raw materials) meets the requirements of the product development team as specified,” said Seil. “Depending on the depth of an organization’s reach, they may delve deeply into a single vendor, or go further and check into the operational details of sub-suppliers in order to ensure the quality of components.”

The MPMs and GSMs at Apple are mostly concerned with internal communication between the planners, the supply chain, and upper management. Wang explained: “The planner wants to know, ‘if I go into upsize, increase my focus by 30 percent, can you support that? Do you have the material? What if I drop 20 percent in next two weeks or months, what will be the impact?”

The supply chain staffers are expected to know everything that is happening in their domain area. It’s not acceptable to say the outside contractor is working on a problem. The staffer is expected to know the exact nature of the problem, what the supplier is doing to fix it, what Apple can do to help solve the problem, and what the next step is. Most of the time, this intelligence is expected in real time – what happened in the last two hours, because frequently, supply chain problems are urgent.

Shortages of products or components are treated seriously and urgently.

It’s often assumed that Apple plans shortages of products. Lines of customers at the stores are seen as marketing coups – public demonstrations that Apple’s products are in high demand, and that shortages are planned for marketing reasons.

But Wang denies that. “We never wanted to have a shortage,” she said. “You want to satisfy every customer that we could.” Wang said it makes no sense that Apple would deliberately make less products than it can sell.

Weekly meet with upper management

Once a week, Apple’s supply managers in Cupertino have a high-level meeting with the VP of operations to review the ongoing manufacturing operation for every product in Apple’s portfolio, from the AppleTV to the iPhone.

The meeting revolves around a set of detailed spreadsheets called the “clear to build,” which is generated by the ERP system Cook installed when he joined Apple in the late 90s. With one report for each product, they are a real time snapshot of the supply chain’s production capabilities, blending the state of component supplies with the latest demand updates from sales and forecasting.

The clear-to-build reports help track and manage all the available materials in stock at all the manufacturing locations in the supply chain that are ready to be assembled into products, hence the name: clear to build.

“It’s pretty sophisticated stuff, used in high-end supply chain management that’s needed when you deal with occasionally difficult-to-procure raw materials and components that may be subject to availability fluctuations due to a myriad of reasons,” said Oliver Seil, VP of design for Belkin. “When you have to build millions of units of something and you need to coordinate hundreds of components, you need to keep risk under control, this is one of the useful tools.”

The high-level planning meeting includes the directors and upper management of operations. It’s to ensure that upcoming production will proceed as planned. The CTB report tries to capture the state of product demand and component supply up to six weeks in advance.

The meeting tends to revolve around gating items – the components or subassemblies that are most likely to hold up production. The term “gating items” is used across a lot of different industries and professions, and generally refers to things that present a hurdle or obstacle to moving forward – hence the term ‘gate.’

“Gating items in a program or project are tasks that need to be completed and may hold up other processes from continuing,” explained Seil. “For example, the development of a working and tested printed circuit board (PCB) may become a gating Item in a project because without it, a proper enclosure’s mechanical design cannot be optimized.”

The VP would go around the room quizzing the Global Supply Managers on gating items. Say the number one gating item is hard drives, the VP or ops would ask the GSM for drives why there was a shortage, how long the shortage might last, what could be done to alleviate the shortage, or whether there is an alternative supply, and so on. Then they would move on to the number two gating item, then the third and so on down the list.

“That’s the MPM’s job: to make sure that you’re very clear minded, and you played a scenario, and sometime we even work the question because planning will also be there.

Oftentimes, the discussion will involve new orders. If Apple just got a big order for thousands of iPads from a school district, will that be a problem? Are there enough components in the supply chain? Which components might be in short supply?

Wang said the meetings were very stressful. The managers were likely to get peppered with questions, and expected to have all the answers, even to unexpected scenarios.

“You wanted to prepare as much as you could,” she said. “Anticipate what scenario would happen. So it’s always very, very stressful. Like before that meeting. You know, because everybody is trying their best to is not to be the gating item.”

As a MPM, Wang tried her best to gather the latest and best, most accurate information about the products she managed before she went into the meeting. She also made sure to upload all the latest data into the clear to build spreadsheet.

“I needed to load everything and there’s a complicated formula in this spreadsheet because there are a lot of what if scenarios that have been planned.”

Sometimes, there would be several ‘what-if’ scenarios that would be discussed at the meeting, making planning even more complicated. “I have to produce like three different ones. So it’s very complicated,” she said.

Each time, the supply managers would be competing with each other NOT to have the number one gating item that is holding up the production. “Nobody wants to be the number one, because that sort of stopping the company from shipping the product,” she said. “If I’m responsible for this commodity, then I’m the one preventing the company shipping product.”

Being responsible for a gating item would be stressful. For Wang, the stress was internal, created by the knowledge that she might be letting the side down. “You wanted to do everything possible, at any cost to solve that problem,” she said.

In the meetings, the most important thing is to demonstrate that the problem is understood, and that’s there’s a plan to address it. “How do I plan to solve it? That’s the most important piece,” she said.

Colleagues would offer a lot of support. The VP and coworkers would generally ask, what can we do to help? “It was very, very supportive,” she said, but paradoxically, that “makes me feel even more stressed, because I feel like I should have known what to do… I know how busy they are. I don’t want them to spend time thinking about the problem that I am supposed to solve. That’s the pressure you give yourself, thinking, ‘I need to do better.’”

Management put an emphasis on creativity and focus. “for this company, you have this this mentality is everything is possible, let’s try harder, let’s be creative, let’s try to solve it. You know we can do it. There’s this can do attitude… people at the leadership level constantly reminded us to be creative. How do you solve the problem?”

Preorder Tim Cook book

Leander Kahney’s new book about Apple’s CEO will be released on April 16, but you can preorder it from Amazon today. “If you’re interested in a great overview of Tim’s still-ongoing tenure at Apple, Leander Kahney’s latest book is exactly what you need …. I highly recommend it.” — Paul ThurrottComplexities of managing supply

There are lots of complexities that have to be managed. Sometimes the contractor runs out of supplies, or makes a component obsolete. Sometimes there is a new version of a component, and the supplier is managing a transition from the old generation to the new. There may be an issue with getting supplies for the new component, or ramping up its production, and so the supplier has to keep producing the old component longer than planned.

“It’s dynamic” said Wang. “There’s a lot of complicated planning going on.”

The managers were constantly trying to avoid ordering too many components or finished products – which have to be paid for – and ordering too few, which would impact supply.

New products always present special challenges to the operations group. There are always technical issues when ramping up production of new technologies. There are quality issues. The yields may be low. The part may have been perfect in small production runs, but quality issues arise when it is made in bigger numbers.

There are also scheduling headaches. The plan might be for a new component to be ready in the millions in 10 weeks; but then technical issues creates a delay, which can cascade up or down the supply chain.

Shortages of components are very common too. A supplier will not be able to deliver an order because it is low on supplies; or its workers are on strike; or there was a fire at the factory. This is usually alleviated by having another supplier pick up the demand.

Interface between suppliers and management

Wang said she loved the job because it called on her to solve complicated problems, and to act as an information conduit between the supply chain and Apple’s upper management.

“Leadership don’t have time to get into all the nitty gritty every time on what happened. So I’m like doing a job is sort of prioritize, collect information and analyze it and prioritize all the problems. So the leadership team with minimum time, they can focus on the right problems. So I thought it was very, it was a fantastic experience and I love everybody that worked over there. From planner to GSM, to my manager to my leadership. And I just feel like it’s sort of a dream job that I would want to have.”

Vendor relationships

Apple has a reputation as a cold-blooded and cutthroat partner for its suppliers, constantly forcing them to push the envelope and cut costs. But Wang said the relationships in general are good and mutually beneficial.

Apple is very hands on. Its engineers spend days, sometimes weeks or months, at suppliers working out problems with them. When Wang worked at Foxconn, customers like Hewlett-Packard or Gateway might spend two hours in a conference room and let the supplier fix any problems, pretty much alone and unsupported. Apple by contrast, would send teams of people down to the production line and see any problems first hand.

“A lot of suppliers love to work with Apple,” she said. “They overcome challenges together and solve problems together… If their vendor is in trouble, especially technically. I mean that’s sort of the trouble for Apple as well. So they will be like roll up their sleeve and they will be working together to solve it.”

Secrecy

Secrecy was also a big deal. Wang never discussed her work with anyone, even colleagues who weren’t working on the same project. “Even the person next to you, I don’t know what they’re working on, and I would not ask because that’s not expected,” she said.

Each project had a different level of secrecy, identified by a scoring scheme and the color. Each color represented the seriousness of the project.

There are purple projects, there are red projects, black projects and double black projects. “Black is more serious than red,” Wang said. “When you get to the level that this is like, let’s say, a triple black project, then you know you’ve got to zip your mouth. Like don’t say anything, ever.”

The secrecy is so watertight, Wang often didn’t know the product she was working to source materials for. She worked for a year on sourcing flex cables for the original iPhone, but had no idea she was working on a phone. She only realized what it was when she saw Steve Jobs unveil it at Macworld.

“When I was working on the first iPhone, the touch module, I didn’t even know it was a phone,” she said. “All I know is that working on new product. I had no idea. Until the day that Steve announced it was a phone.

“And I was literally in the audience at the same time understanding wow that was actually a phone. I had no idea.”

iPhone growth

Every year, the iPhone manufacturing operation would grow massively. In general, each new iPhone model sold as many as all the previous generations combined.

In the early days, growth was even more explosive. The first iPhone sold 1.39 million units. The following year, the iPhone sold 11.6 million units – a 10X increase. In 2009, 20.7 million units were sold, double the year before. Sales doubled again in 2010 (39.99 million units sold) and nearly doubled again in 2011 (72.29 million) and in 2012 (125 million).

The explosive growth in sales began slowing a little in 2013 and 2014 (150 million and 169 million respectively) before there was a big jump in 2015, the year the bigger-screen Plus size iPhones were first introduced, with sales of 231.22 million units. Annual sales dipped slightly in 2016 and 2017 (211 million and 216 million units sold, respectively), suggesting that Apple’s sales have flattened out at about 220 million units a year.

In the early years, the supply chain for that number of components wasn’t well established, and the team scrambled to find suppliers everywhere they could. “You just have to go everywhere possible and to look for the capacity,” said Wang. “Whether it’s a building a factory, whether it’s finding a substitute technology or a material. It’s just a huge job for us.”

It wasn’t as easy. It often takes a couple of years to build and equip a factory (Foxconn could build an assembly plant in weeks, but these are often bare-bones buildings for final assembly without specialized manufacturing equipment). Apple’s problem was compounded by the fact that the company was never certain how big the iPhone would grow. It was difficult to forecast. No one had any idea that it would grow as big as it did.

In addition, the design team and the engineers were constantly pushing the technology. Every year they made the iPhone thinner and thinner, with sharper screens and better cameras and battery life. New technologies meant new suppliers, which were difficult to find, especially at scale. “It’s just phenomenal… it’s a very, very hard job,” Wang said.

It’s tricky to introduce new technology. The scale is so vast, there has to be an infrastructure, a supply chain, in place. It’s no good to find a new technology that can only be made in small numbers. For iPhone scale, a new technology has to be produced in tens of millions of units. It can sometimes take five years for a great technology in the lab to be mass produced at scale. Samsung for example, has been showing flexible OLED screens at CES for several years, but it has not yet set up the factories to make them at mass scale.

For example, it was a huge problem to source enough interconnects, the tiny cables that connect the iPhone’s internal components. There are 8 to 12 interconnects used in the latest iPhones. They are known as a flex ‘module’ because the cables often included other components at each end – hence it’s not just a cable, but a module. It was a huge problem to source enough flex modules.

When Apple started using them, they were a niche, specialist technology used in limited numbers in the aerospace and automotive industries, with a very limited number of suppliers, mostly in Japan.

They were used for the first time by Apple in the iPod’s capacitive scroll wheel. Wang introduced the iPhone engineering team to the technology when she was working as the global supply manager for interconnects, which included flex cables.

Ramping up was “super, super hard,” she said. Within a year of the iPhone’s launch, Apple was working with 30 plus factories just for the flex cables. Wang memorized the details of each and every factory. She knew their production schedules, the warehouse capacities, the number of workers, where and how they recruited new workers. She knew everything about the factories in very, very granular detail. “I feel like it’s almost like an art,” she said. “Because there are certain scientific information going there. But there’s a lot of guesstimates as well as educated intelligent guesses, right? Because of all the experience you accumulated.”

At one point, the flex cables became the number one gating item for the iPhone because one factory in Japan couldn’t hire and train enough workers to keep up with the demand. Wang helped the factory find third-party recruitment agencies to find extra workers – a bit of creative thinking that earned her some praise.

Apple tried not to add too many new suppliers to quickly. Each new supplier presented a new management challenge.

Wang estimated there were at least 15 people in the field just for these 30 factories – two apiece. Each iPhone has about 10 flex cables or modules. Some are fairly simple and are relatively easy to produce; others are trickier and the yields from the factories are less predictable.

Automated lines with robots don’t present much challenge. It’s easy to calculate the yield because robots don’t make many errors. They are consistent. But yields on manual production lines are much less predictable. Human workers make more mistakes, and work at different paces. Long and complex assembly chains can have widely disparate yield numbers.

To get a good idea of the yields for planning purposes involves a whole team of people—operations engineers, forecasting folks, yield specialists who can predict accurate yields, and engineers who might be able to find alternative technologies if supplies are short.

If every generation of the iPhone grew 10x, that’s 10x more supply, and 10x more factories, 10x more Apple staffers and planners and pertains folks to oversee the operation.

Apple tried not to grow the number of suppliers too big or too fast, because of the overhead involved. “You need a lot of resources to manage them,” Wang said.

Tim Cook’s culture of questions permeates the company

Cook’s approach to managing operations is inculcated into the operations team. Like Cook, senior managers often drill down into potential issues, making sure staffers have a handle on problems, and more importantly, on solutions. Wang said managers often adopt Cook’s habit of asking question after question to get to the root of a problem.

“It’s almost like peeling onion kind of exercise,” said Wang. “All the senior management at Apple does that.”

In a meeting, Wang might report that there was a problem shipping a product. The management would ask why? And she would explain it’s a yield problem. The manager would ask what caused the yield problem, and she would explain the root cause.

“They want to know do you understand the problem?” she said. “They’re going to go down to a very much root level, trying to understand the problem.”

Wang said like Cook, a lot of senior operations managers were detail-oriented with an uncanny knack for numbers.

Most if the senior managers were almost Rain Man like in their abilities with numbers. She often saw senior leadership seemingly memorize entire spreadsheets, or zero in on obscure cells with an aberrant number. They had the uncannily ability to spot a problem in a sea of numbers that could easily be overlooked. Managers would often remembered numbers from meeting to meeting, and would question the supply managers if a number changed.

“They know exactly what to look for and then they memorize it,” she said. “You will be caught on the spot if you are not really detail oriented.

“He definitely created a lot of process that practices how you are thinking about a problem as well as the culture and the norms of the company,” she said. “A lot of time you hear people say, ‘that’s how we do it.’ I think that’s either inspired by him or impacted by him. The way how we think and how he does things.”

Wang didn’t interact with Cook in her day-to-day job, but would sometimes have to prep her director when he had a meeting with Cook or other senior operations leaders.

“Sometimes he would get called to meet with Tim because he needs to know more a lot more detail. So when that moment comes, then you would have to prep your director. Very hard, in terms of you know, so they know everything then they’re able to have that conversation with Tim.

“If you’re not detail oriented, I don’t think you can even survive in that company.”

![How Ops operates back at Apple HQ [Cook book outtakes] Apple leases new offices near to Apple Park](https://www.cultofmac.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Apple-Park.jpg)