The world had never seen anything like the iPhone when Apple launched the device on June 29, 2007. But the touchscreen device that blew everyone’s minds immediately didn’t come about so easily.

The world had never seen anything like the iPhone when Apple launched the device on June 29, 2007. But the touchscreen device that blew everyone’s minds immediately didn’t come about so easily.

The iPhone was the result of years of arduous work by Apple’s industrial designers. They labored over a long string of prototypes and CAD designs in their quest to produce the ultimate smartphone.

This excerpt from my book Jony Ive: The Genius Behind Apple’s Greatest Products offers an inside account of the iPhone’s birth.

This post contains affiliate links. Cult of Mac may earn a commission when you use our links to buy items.

An early demo of multi-touch technology

One morning in late 2003, just before the launch of the iPod mini, Jony Ive and his team gathered for a bi-weekly brainstorming meeting. As usual, the team assembled around the studio’s kitchen table. One of the industrial designers, Duncan Kerr, did a show-and-tell. Kerr, who joined Apple’s design team in 1999 after having spent a few years working at IDEO, had a lot of engineering experience, and he loved to tinker with new technology.

Kerr had been working with Apple’s Input Engineering group, which was exploring alternative inputs for the Mac, with the hope of doing away with the keyboard and mouse, the mainstay of computing for more than three decades. When Kerr told the group about what he’d learned, his words were greeted by some stunned expressions.

“It was amazing,” said Doug Satzger, shaking his head in disbelief. “It was a really amazing brainstorm.”

Around the table was the core industrial design group: Jony, Richard Howarth, Chris Stringer, Eugene Whang, Danny Coster, Danny De Iullis, Rico Zorkendorfer, Shin Nishibori, Bart Andre, and Satzger.

“I remember Duncan showing us how, with multi-touch, you could do different things with two fingers and with three fingers,” recalled Satzger. “He showed us on-screen rotating and zooming—and I was really surprised that we could do that stuff.”

That morning was the first time the team had even heard of multi-touch. Today it doesn’t seem exceptional, but back then, touch interfaces were pretty primitive. Most touch devices, such as Palm Pilots and Windows tablets, used a pen or stylus. Screens that were sensitive to fingers, not pens, like ATM screens, were restricted to single presses. There was no pinching or zooming, no swiping up and down or left and right.

Kerr explained to his colleagues that the new technology would allow people to use two or three fingers instead of just one, and that it would afford much more sophisticated interfaces than simple single-finger button presses.

Brainstorming about multi-touch devices

Excited by Kerr’s explanation of what a sophisticated touch interface could do, the team members started to brainstorm the kinds of hardware they might build with it. The most obvious idea was a touchscreen Mac. Instead of a keyboard and mouse, users could tap on the screen of the computer to control it. One of the designers suggested a touchscreen controller that functioned as an alternate to a keyboard and mouse, a sort of virtual keyboard with soft keys.

As Satzger remembered, “We asked, How do we take a tablet, which has been around for a while, and do something more with it? Touch is one thing, but multi-touch was new. You could swipe to turn a page, as opposed to finding a button on the screen that would allow you turn the page. Instead of trying to find a button to make operations, we could turn a page just like a newspaper. I was really surprised you could do this stuff.”

Jony in particular had always had a deep appreciation for the tactile nature of computing; he had put handles on several of his early machines specifically to encourage touching. But here was an opportunity to make the ultimate tactile device. No more keyboard, mouse, pen, or even a click wheel—the user would touch the actual interface with his or her fingers. What could be more intimate?

The Input Engineering team had built a giant experimental system to test multi-touch. It was a big capacitive display about the size of a ping pong table, with a projector suspended above it. The projector shone the Mac’s operating system onto the array, which was a mass of wires.

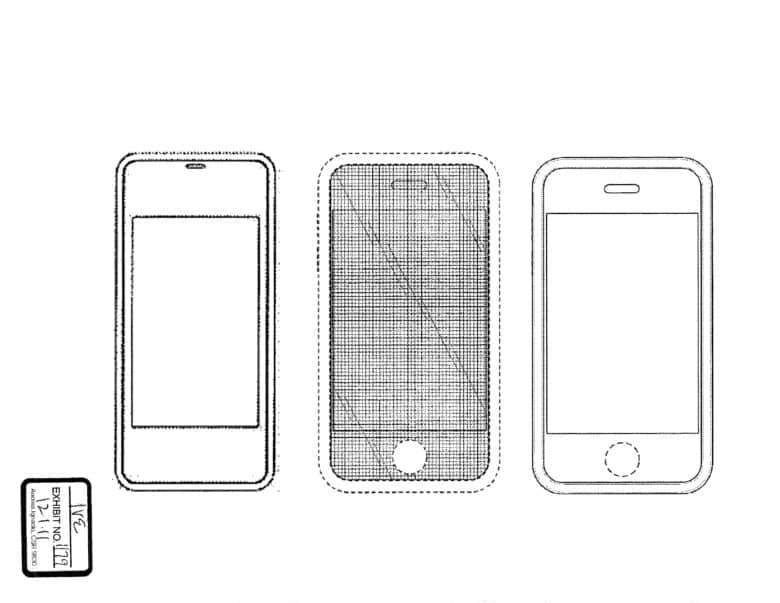

Photo: Apple/Samsung trial

“This is going to change everything,” Jony told the design team after he saw it. Jony wanted to show the system to Steve Jobs, but he was afraid his boss would pour cold water on it since it was still raw and unpolished. Jony reasoned that he had to show the work in progress to Jobs in private, with no one else around.

“Because Steve is so quick to give an opinion, I didn’t show him stuff in front of other people,” Jony said. “He might say ‘This is shit,’ and snuff the idea. I feel that ideas are very fragile, so you have to be tender when they are in development. I realized that if he pissed on this, it would be so sad because I know it was so important.”

Jony followed his instincts and showed Jobs the system in private. The gambit worked, and Jobs loved the idea. “This is the future,” said Jobs.

With Jobs’ seal of approval, Jony directed Imran Chaudhri and Bas Ording, two of Apple’s most talented software engineers, to shrink the massive capacitive array into a working tablet prototype. Within a week, they came back with a twelve-inch MacBook display hooked to a big tower Power Mac, which provided the computing power to interpret the finger gestures.

They showed Jony and the designers a demonstration with Google Maps. After bringing up Apple’s Cupertino HQ, one of them spread his fingers apart on the screen, zooming in on the campus. The designers were astonished “We could zoom in and zoom out with touch gestures onto the Apple campus!” said Satzger.

Building a finger-controlled tablet looked like a real possibility. It wouldn’t happen overnight and, thanks to market forces, another revolutionary Apple product would emerge from the pipeline first.

The iPhone prototype known as ‘Model 035’

Multi-touch might have been new to Jony’s design team, but it wasn’t new in academia. The origins of the technology stretched back to the ‘sixties, when researchers worked out the first crude electronics for touch-based sensors. Systems that could detect multiple touches simultaneously were invented in 1982 at the University of Toronto, and the first workable multi-touch screens appeared in 1984, the same year Steve Jobs launched the Macintosh. The marketplace didn’t see multi-touch products until the late ‘nineties. Among the first were a gesture-based input pad for computers and a touch-sensitive keyboard-cum-mouse, from a small Delaware company called FingerWorks.

Early in 2005, Apple quietly acquired FingerWorks and immediately pulled its products from the market. News of the buyout didn’t leak for more than a year, when the two FingerWorks founders, Wayne Westerman and John Elias, started filing new touch patents for Apple.

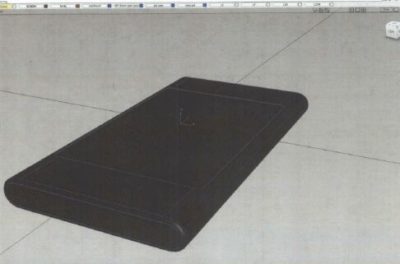

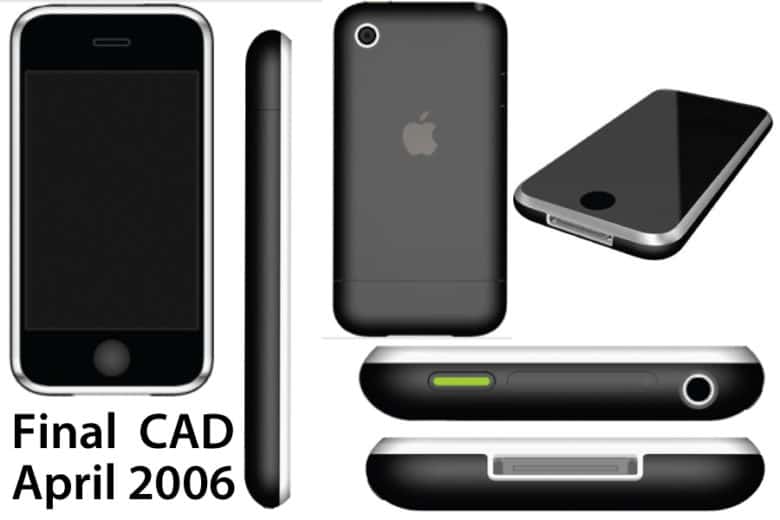

After Chaudhri and Ording’s crude mockup showed that a finger-controlled tablet would work, Jony’s industrial design team set about building more finished prototypes. Bart Andre, who also has a mechanical bent, and Danny Coster led the design work. One of the prototypes they created, known internally as “Model 035,” formed the basis for a patent filed on March 17, 2004.

Model 035 was a large, white tablet that looked like the lid of one of Apple’s white plastic iBooks from the time. Though it lacked a keyboard, it was based on iBook components. The 035 had no home button and a significantly thicker and wider base than would the 2010 iPad. But the two devices share rounded edges and a black bezel surrounding the screen. It ran a modified version of Mac OS X (the mobile version of the software, iOS, was still years away).

Photo: Apple/Samsung trial

Photo: Apple/Samsung trial

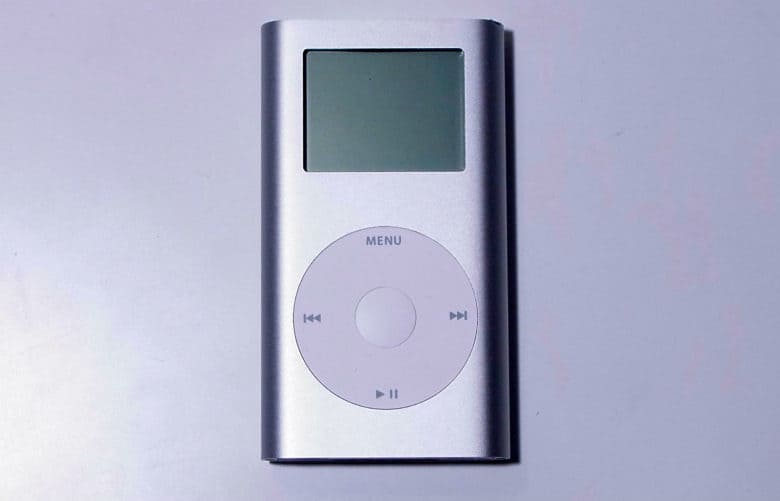

While Jony’s team worked on several tablet prototypes, Apple’s executives were worrying about the iPod. It was flying high: Apple sold two million in 2003, ten million in 2004, and forty million in 2005. But it was becoming clear that the mobile phone would one day supersede the iPod. Most people were carrying around both an iPod and a cellphone. At that stage, cellphones could store a few tunes, but it was becoming clear that, sooner rather than later, someone, perhaps a competitor, would combine the two devices.

In 2005, Apple teamed up with Motorola to release an “iTunes phone” called the Rokr E1. It was a candy bar-shaped phone that could play music purchased from the iTunes Music Store. Users could load songs through iTunes and play them through an iPod-like music app. But the limitations of the phone doomed it from the start. It could hold just one hundred songs; transferring songs from a computer was slow; and the interface was horrible. Jobs could barely conceal his disdain for it.

On the other hand, the Motorola Rokr phone made it apparent to all concerned that Apple needed to make its own phone. Customers wanted the experience of a full iPod on their phones, but, given Jobs’ insistence on Apple standards, another company could hardly be trusted to get it right.

Precisely how the project that had produced Model 035 got re-tracked into making the iPhone is a matter of dispute. During an appearance at the 2010 All Things D conference, Jobs took credit for having come up with the idea for a touch screen phone.

“I’ll tell you a secret,” Jobs told the crowd. “It began with the tablet. I had this idea about having a glass display, a multi-touch display you could type on with your fingers. I asked our people about it. And six months later, they came back with this amazing display. And I gave it to one of our really brilliant UI guys. He got scrolling working and some other things, and I thought, ‘My God, we can build a phone with this!’ So we put the tablet aside, and we went to work on the iPhone.

The quest for a smarter smartphone

Others at Apple at the time have a different recollection of the beginnings of their iPhone pursuit. They say the idea came up during one of the regular executive meetings.

“We all hated our phones,” recalled Scott Forstall, a software executive. “I think we had these flip phones at the time. And we were asking ourselves, could we use the technology we were doing with touch that we’d been prototyping for this tablet and could we use that same technology to build a phone, something the size that could fit in your pocket, but give it all the same power that we were looking at giving to the tablet?”

After the meeting, Jobs, Tony Fadell, Jon Rubenstein, and Phil Schiller went over to Jony’s studio to see a demo of the 035 prototype. They were impressed by Jony’s demonstration of the 035, but expressed doubts that the technology would work for a cell phone.

The crucial breakthrough was the creation of a small test app that used only part of the 035 tablet’s screen.

“We built a small scrolling list,” said Forstall. “We wanted it to fit in the pocket, so we built a small corner of it as a list of contacts. And you would sit there and you’d scroll on this list of contacts, you could tap on the contact, it would slide over and show you the contact information, and you could tap on the phone number and it would say calling. It wasn’t calling, but it would say it was calling. And it was just amazing. And we realized that a touchscreen that was sized, that could fit into your pocket, would work perfectly as one of these phones.”

Years later, Apple attorney Harold McElhinny would describe the immense amount of work the project required. “It required an entirely new hardware system…. It required an entirely new user interface and that interface had to become completely intuitive.” He also said Apple took a huge leap of faith moving into a new product category. “Think about the risk. They were a successful computer company. They were a successful music company. And they were about to enter a field that was dominated by giants…. Apple had absolutely no name in the [phone] field. No credibility.”

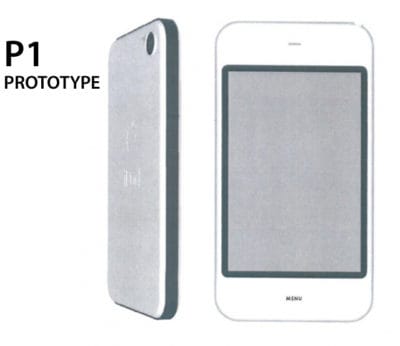

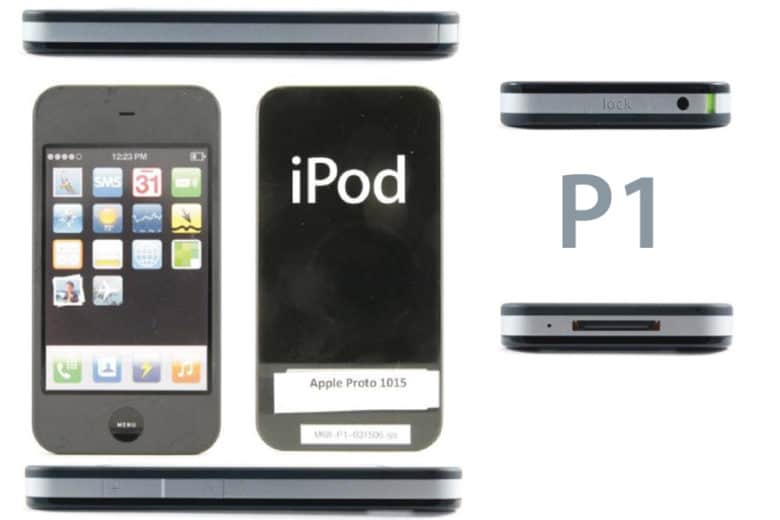

Parallel iPhone projects: P1 and P2

McElhinny also said he firmly believes that had the project gone wrong, it could have destroyed the company. To mitigate the risk, Apple’s executives hedged their bets. They would develop two phones in parallel and pit them against each other. The secret phone project was codenamed “Purple,” shortened to just “P.” One phone project, based on the iPod nano, got the codename P1; the other phone, led by Jony, was a brand new multi-touch device based on the 035 tablet, codenamed P2.

The P1 project was led by Fadell; his group had the idea to somehow graft a phone onto a current iPod. “It was actually a natural progression of taking the iPod, which we already had, and morphing it into something else,” said the former executive.

Matt Rogers, a hotshot young iPod engineer who worked for Fadell, was given the job of creating the software for the device. As an intern, Rogers had previously impressed Fadell by rewriting some complex testing software for the iPod. As usual, the research was a big secret. “Nobody in the company knew we were working on a phone,” said Rogers. It was also a lot of extra work. At the time, the iPod team was also working on a new iPod nano, a new iPod classic and a shuffle.

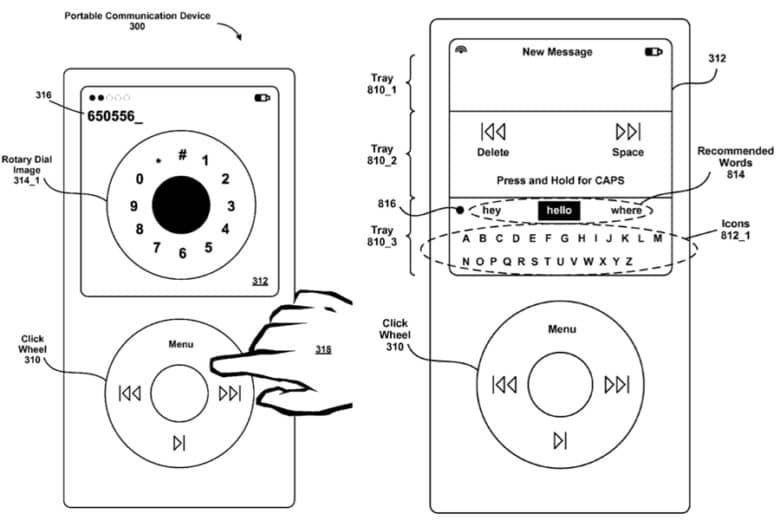

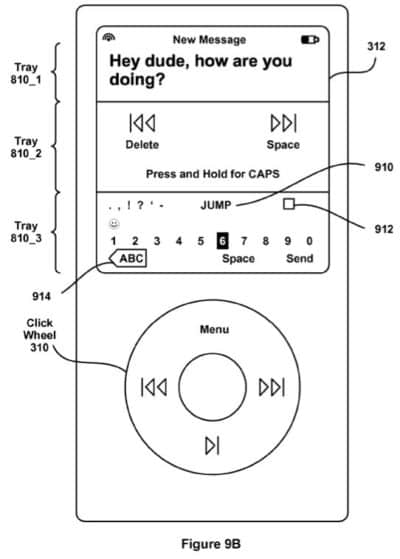

Image: Apple/United States Patent and Trademark Office

After six months of effort, Fadell’s team produced a prototype iPod-plus-phone that worked, more or less.

Image: Apple/United States Patent and Trademark Office

Apple filed a couple of patents from their experimentation. One of them suggested that the iPod-plus-phone could create text messages with a predictive text system. Jobs, Forstall, Ording, and Chaudhri, among others, were named as inventors.

But the P1 had too many limitations. Just dialing a number was a pain, and the device was too limited. It couldn’t surf the Net; it couldn’t run apps.

Fadell said later that the iPod-plus-phone was a “heated topic” of discussion at Apple. The biggest problem was that forced the team into a design corner. Using the existing device limited their design options in a way that was not optimal to the task. “[The P1] had a little screen and this hardware wheel and we were stuck with that … but sometimes you have to try things in order to throw it away.”

After six months of work on the iPod-plus-phone P1, Jobs killed the project.

“Honestly, we can do better guys,” he told the team.

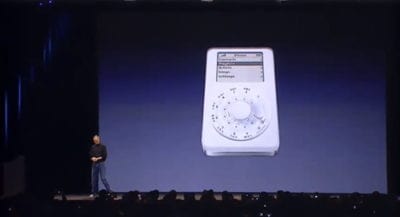

Photo: Apple

“We all know this is the one we want to do” Jobs said, referring to the P2. “So let’s make it work.”

Two years later, during the iPhone introduction at Macworld, Jobs jokingly flashed an image of an iPod with a rotary dialpad on its screen. This was how not to build a new phone, Jobs said, as the audience laughed. Few knew the company might well have produced just such a phone.

A new team takes charge of iPhone

After the decision to move forward with the P2, Jony was put in charge of industrial design, Fadell of engineering, and Forstall, previously responsible for Mac OS X, was given the job of adapting the computer operating system into a brand new operating system for the phone.

Jony’s design team worked on the iPhone without ever seeing the operating system. They initially worked with a blank screen and later, a picture of the interface with cryptic mock icons. Likewise, the software engineers never got to see the prototype hardware. “I still don’t know what the lightning icon means,” one of the designers later remarked, referring to one of the icons on the fake iOS screen.

Jony himself wasn’t left in the dark: He was kept up to speed on the latest developments in Forstall’s new operating system, and was constantly talking to Jobs and other executives. He’d give feedback and direction to the design team. Within the design studio, designer Richard Howarth was designated the design lead of the Purple project.

At the beginning, few of those involved were confident they would be able to develop a phone.

“It was fundamental R&D in all directions,” said a former executive. It meant ramping up probably the most difficult project in the company’s history and, all the while, continuing to develop products like the MacBook and the iPod line. Important staffers were moved off their current projects, delaying some products and cancelling others.

There were potentially dire consequences for the company if the project did not succeed. “Had it not succeeded, not only would we have had the detriment of the lack of those products shipping, we wouldn’t have had something else to fill in at the same time,” Forstall explained.

Jobs told the executives they could recruit anyone they wanted within the company to work on the project, but they absolutely could not go outside.

“That was quite a challenge,” Forstall recalled. “The way I did it is I would find people who were true superstars at the company, just amazing engineers, and I would bring them to my office and I would sit them down and I would say, ‘You are a superstar in your current role. Your manager loves you. You’re going to be incredibly successful at Apple if you just stay in your current role and keep on doing what you want to do. I have another offer for you, another option. We’re starting a new project. It’s so secret, I can even tell you what that new project is’ … And amazingly, some tremendously talented people accepted that challenge and that’s how I put together the iPhone team.”

Inside Apple’s ‘Purple Dorm’

Forstall commandeered an entire floor in one of the buildings at Apple HQ and had it locked down. “We put doors with badge readers, there were cameras, I think, to get to some of our labs, you had to badge in four times to get there,” he said. It was nicknamed the “Purple Dorm.”

“People were there all the time,” Forstall said. “They were there at night. They were there on weekends. You know, it smelled something like pizza.

“On the front door of the purple dorm, we put a sign up that said ‘Fight Club’ because the first rule of Fight Club in the movie is you don’t talk about Fight Club, and the first rule about the purple project is you do not talk about that outside of those doors.”

Image: Apple/Samsung trial

Over in IDg, Jony began, as usual, with the iPhone’s story. As he later explained, it was all about how the user would feel about the device. “When we are at these early stages in design, when we’re trying to establish some of the primary goals—often we’ll talk about the story for the product—we’re talking about perception. We’re talking about how you feel about the product, not in a physical sense, but in a perceptual sense.”

Jony believed the iPhone would be all about the screen. In their earliest discussions, the designers agreed that nothing should detract from the screen, which Jony likened to an “infinity pool,” those high-end swimming pools with an invisible edge.

“What that did was make it very clear in our minds that the display was important, and we wanted to develop a product that featured and deferred to the display,” he said. “Some of our early discussions about the iPhone centered on this idea of… this infinity pool, this pond, where the display would sort of magically appear.” The team made a point in exploring design ideas to avoid any approaches that would diminish the importance of the display.

Jony said they wanted the display to be “magical” and “surprising.” These were his high-end goals for any eventual design. “In the earliest stages of this design, this seemed—this was very new, and it felt there was real opportunity to develop a design story based on those sorts of preoccupations,” he later explained.

iPhone prototypes: Extrudo and Sandwich

Photo: m-s-y/Flickr CC

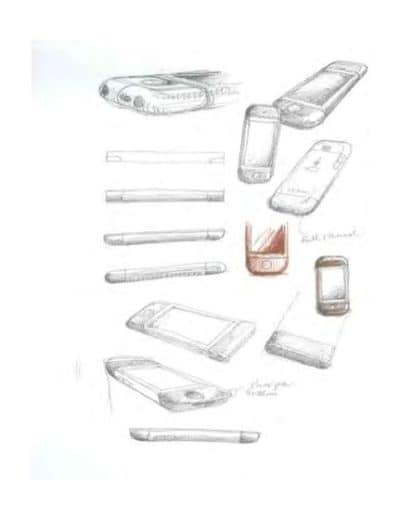

Late in the fall of 2004, Jony’s design team began work on two distinct design directions.

Image: Apple/Samsung trial

Apple already had big production lines making and anodizing iPod cases in huge numbers. That was one advantage of that direction, along with the fact that Jony and team loved what could be done with extrusion.

The other design, called “Sandwich,” was led by Richard Howarth. Made mostly of plastic, with a plastic screen, the Sandwich design was rectangular with evenly rounded corners. It had a metal band running around the midpoint of its body, a centered display on the front face, a menu button centered below the screen, and a speaker slot centered above the screen.

Jony and his team preferred the Extrudo look and gave it the most attention. They tried cases that were extruded along the X-axis, and some along the Y-axis. But problems surfaced immediately. Extrudo’s hard edges hurt the designers’ faces when they put it up to their ears. Jobs especially hated this.

Photo: Apple/Samsung trial

Photo: Apple/Samsung trial

To make the hard edges softer, plastic end caps were added, which also helped with the radio antennas. The iPhone would have three radios: Wi-Fi, Bluetooth and a cell radio. But radio waves won’t pass through a metal shell, so the plastic endcaps became essential.

Image: Apple/Samsung trial

Image: Apple/Samsung trial

The team struggled to solve Extrudo’s problems, but engineering tests made it clear this particular design direction wouldn’t work unless the plastic end caps for the radios got bigger.

But bigger caps would ruin the clean Extrudo look.

“We made books and books filled with pages of designs trying to figure out how not to break up the design because of the antenna, how not to make the earpiece too hard and sharp, and so on,” said Satzger. “But it seemed like all the solutions that added comfort detracted from the overall design.”

Image: Apple/Samsung trial

The Extrudo design had another problem that nagged at Jobs: The metal bezel detracted from the screen. The design didn’t “defer” to the screen, which had been one of Jony’s original goals. Jony later recalled his flush of embarrassment when Jobs pointed it out.

Apple killed Extrudo; the team was left with Sandwich.

The Sandwich design did have several advantages over Extrudo, one of which was that the rounded edges didn’t hurt the designer’s ears. But the engineering prototypes came back big and chunky, and Jony’s team struggled to slim it down.

They were trying to cram in a lot of technology, much of which hadn’t yet been miniaturized enough for a device as complex as the phone everyone envisioned.

Image: Apple/Samsung trial

The Jony Phone

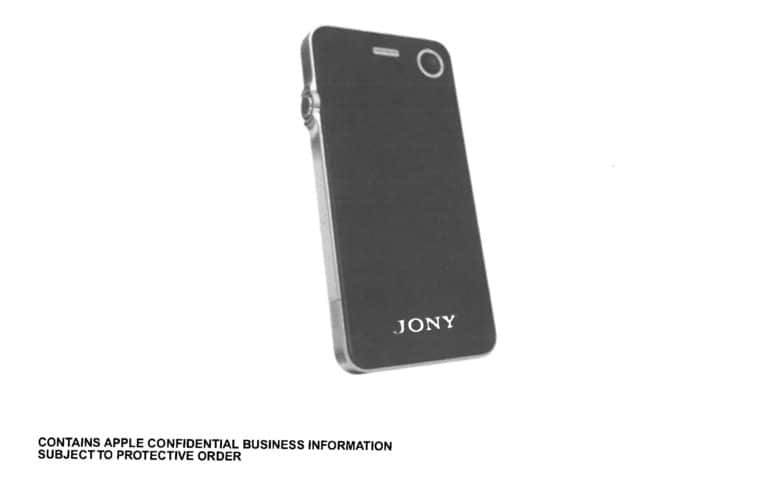

By February 2006, several redesigns had come and gone. Jony was so dissatisfied with the progression that, during one of the brainstorms, he asked designer Shin Nishibori to make an exploratory version of the phone with Sony-style design cues.

Later, he would contend that his request was not to copy Sony specifically, but to inject some fresh, “fun” ideas into the process.

Shin Nishibori had been a well-known young designer in Japan for years before coming to work at Apple. Traces of a Sony/Japanese influence have appeared in Nishibori’s work on Apple products since 2001, and Steve Jobs, Jony, and other Apple designers had often expressed admiration for Japan’s minimalist aesthetic.

In February and March 2006, Nishibori designed and built several phones that borrowed elements seen in Sony products of the time, including a jog wheel, which was a control-wheel-cum-switch that was used on Sony’s Clie personal digital assistants. Nishibori even put the Sony logo on the backs—except for one that he jokingly labeled a Jony.

Years later, at the Apple-Samsung trial, one of Nishibori’s mock Sony phones would be presented as evidence that Jony’s design team hadn’t developed the iPhone on their own, as they contended, but instead copied other companies’ designs. But Apple successfully argued that the Sony/Jony design was merely Sony-style decoration on a device they’d already designed. As Apple’s attorneys pointed out, Nishibori’s designs are asymmetrical and none of Sony-style buttons and switches were adopted in the released iPhone.

Photo: Apple/Samsung trial

In early March 2006, Richard Howarth expressed his frustration with the state of the development of P1. In comparing P1 to Nishibori’s Sony-style design, Howarth complained about its size, and how Nishibori had managed to achieve a slimmer profile. “Looking at what Shin’s doing with the Sony-style chappy he’s able to achieve a much-smaller looking product with a much nicer shape to have next to your ear and in your pocket,” Howarth wrote in an email to Jony.

“I’m also worried that if we start cutting volume buttons on the side, then it removes some of the purity of the extrusion idea and seems like the wrong shape for the job. We can only add so much to it before it becomes a style/a shape, rather than the most efficient construction method and that would be bad.”

Photo: Apple/Samsung trial

Photo: Apple/Samsung trial

Jony’s team had also tried a curved design, which at one point looked like a promising direction. By adding a curve, more technology could be packed into the middle bulge. It’s a trick Apple has used in many of its newer products, from the iPad to the iMac.

From the beginning, Satzger remembered, the team had a “strong interest” in a design that used two pieces of shaped glass. One of the prototypes they built had a split screen. Above was the screen, below a software-driven touchpad that changed depending on function. Sometimes it was a dial pad, at other times a keyboard. But the problem of making glass convex proved too difficult.

Although Howarth was still using the Extrudo design as a comparison piece late in development, engineering tests seemed to affirm that the Sandwich-style direction would prevail. Then engineering prototypes of the Sandwich design came back with a bad report: They were too big and fat. With the realization that all the technology just couldn’t be squeezed into a pleasing shape, the decision was made to kill the Sandwich design, too.

“We didn’t know enough about antennas, we didn’t know enough about acoustics, we didn’t know enough about packing everything in,” said one former executive. “It worked, but it just wasn’t attractive.”

Back to the drawing board

Image: Apple/Samsung trial

Faced with a dead end, Jony’s team reversed course. They turned to an old model they’d made early in the process but had discarded in favor in Sandwich and Extrudo.

The discarded model looked very similar to the phone that would actually ship, with an edge-to-edge screen interrupted only for the single Home button. Its gently curved back snapped seamlessly onto the screen, like the original iPod. Most importantly, it maintained Jony’s infinity pool illusion. When the phone was off, it appeared to be a single, unbroken, inky-black faceplate; when switched on, the screen magically appeared from within.

It was a viola! moment.

“We found something that we’d overlooked,” said Stringer, “something that we, once adding detail to it and really spending some time with it, decided was the absolute best choice for us at that time.” He remembered the ease with which the final, unornamented design for iPhone was chosen. “It was the most beautiful of our designs,” he explained. The front face bore neither the company logo nor the name of the product. “We also knew from our experience with iPod,” Stringer explained, “if you make a startlingly beautiful and original design, you don’t need to. It stands for itself. It becomes a cultural icon.”

Image: Apple/Samsung trial

In the fullness of time, Jony would resurrected the Sandwich for the iPhone 4, another example of the team revisiting earlier designs and spying qualities that they’d previously overlooked.

The main structural element of the iPhone 4—the steel frame between the two plates of glass—would double as the phone’s antennas. Unfortunately, that proved problematic, since, if the user’s hand made a contact between a gap, effectively shorting the two antennas, the phone would drop calls. Reportedly, Apple could have easily avoided the issue if the antenna had been clear coated, but Jony didn’t want to ruin the integrity of the metal.

Beyond matters of form, the team focused on the function of the multi-touch. Most touch devices at the time were used resistive touch screens, based on two thin sheets of conductive material separated by a thin gap of air. When the screen is pressed, the two layers make contact, registering the touch. Resistive screens were typically made of plastic, and were common in pen-based devices like Palm Pilots and Apple’s Newton.

Jony’s design team tried using a resistive screen for the iPhone, but were unsatisfied with the results. Pressing on the screen distorted the picture, and the screen tired the fingers because the user had to press pretty hard. It just didn’t live up to the promise of the name (“touch screen”) which the designers thought should convey the illusion that the user was literally touching the content.

Moving on from the resistive screen, the hardware team set out to build screens based on capacitive touch, registering changes in electrical charges (or capacitance) across its surface. Human skin is electrically conductive, and a capacitive touchscreen uses that characteristic to detect even the lightest touch. Apple had been using capacitive touch technology for several years with the iPod scroll wheel, laptop trackpads, and the Power Mac Cube, which had a capacitive on/off button. But the technology hadn’t been applied to transparent screens.

One problem was that there was no supply chain for capacitive screens. No one was producing them on an industrial scale at the time—but Apple found a small company in Taiwan called TPK that was producing them for point-of-sale displays using an innovative but limited-run technique. Jobs made a handshake deal with the company, promising that Apple would buy every screen the factory could produce. Based on this agreement, TPK invested $100 million to rapidly ramp up their manufacturing capabilities. They ended up supplying about eighty percent of the screens for the first iPhone, growing rapidly to a $3 billion business by 2013.

iPhone screen: From plastic to glass

While Apple’s operations group was working out how to manufacture the iPhone, Jony’s design team was having doubts about their original choice of material for the screen.

Jony and his team planned to use plastic, mostly because it was shatterproof. Although all of the iPhone prototypes all had plastic screens, the designers were never happy with it.

“The original plastic face had this weird flexibility to it,” said Satzger. “It was a matte finish. If it goes to glossy plastic, you see this waviness to it, which makes it look really crappy.” Jony instructed the team to try textured plastic, but that didn’t work either. In a gutsy next move, they decided to try glass, despite the facts that glass breaks easily and no one had made a consumer electronic device with such a big piece of glass.

The story of the shift to glass is variously remembered: Although Jony’s group was already investigating glass, Jobs is credited by some as initiating the move to glass. As the story goes, he’d been using an iPhone prototype, which he kept in his pocket with his keys. He was reportedly furious that they scratched the screen.

“I won’t sell a product that gets scratched,” Jobs said later. “I want a glass screen, and I want it perfect in six weeks.”

Apple turns to Corning superglass

A deeper version has it that the development took more like six months in advance of launch, not six weeks. Apple’s operations group was charged with finding the strongest glass available. The search led them to Corning Inc., a glass manufacturer headquartered in upstate New York.

In 1960, Corning had created a nearly unbreakable reinforced glass they called “muscled glass” or Chemcor. The key to its manufacture was an innovative chemical process in which glass is dipped into a hot bath of potassium salt. Smaller sodium atoms leave the glass, and are replaced by bigger potassium atoms from the salt. When the glass cools, the bigger potassium atoms are packed in so tightly they give the glass exceptional damage resistance. The glass can withstand pressures of 100,000 pounds per square inch (normal glass handles about 7,000).

Chemcors’s market future seemed bright, but it never took off. Other than its use in some airplanes and American Motor Javelin cars, the material sold poorly and Corning discontinued it in 1971.

When Apple’s Ops group came calling in 2006, they found Corning had been thinking about bringing back the old superglass for a couple of years. They’d seen Motorola use glass for its Razr v3 phone and begun to explore ways to make Chemcor thin enough to be suitable for cell phones.

Jony’s ID group came up with spec: The glass needed to be 1.3mm to fit into the iPhone design. Jobs told Corning’s CEO, Wendell Weeks, they had six weeks to create as much of it as they could. Weeks replied they didn’t have the capacity and actually, Chemcor had never been created in this way or in such volume. “None of our plants make the glass now,” he told Jobs. But Jobs cajoled the CEO. “Get your mind around it,” he said. “You can do it.”

Almost overnight, the company completely remade its manufacturing processes, based in Kentucky, changing several of its LCD-making plants to muscled glass, by then renamed Gorilla glass. In May 2007, Corning was making thousands of yards of Gorilla glass.

Corning’s glass, in combination with the aluminum back, marked another change in Jony’s design language. In was a striking, almost shocking, minimalism in hard metal and glass.

To hold the glass screen in place, Jony’s team came up with a shiny stainless steel bezel, which doubled as a structural element. The bezel would give the iPhone strength, but it also needed to look good.

Jony’s team worried that the glass would smash if the phone was dropped. “We were putting glass in close proximity to hardened steel,” said Satzger, who pointed out that, “if you drop [the phone], you don’t have to worry about the ground hitting the glass. You have to worry about the band of steel surrounding the glass hitting the glass.”

The solution was a thin rubber gasket between the glass screen and the stainless steel bezel. But the gasket created a gap that, at least at first, the designers hated for a very personal reason. “Because many of us in the ID team rarely shaved and had beard stubble, it used to yank our facial hair when we held the device up to our faces,” said Satzger, laughing at the memory. The team played around with gap size until they got it right. “We designed several increments of gap size between the metal and glass until we got one that didn’t yank our face hair.”

Countdown to Macworld

One morning in the fall of 2006, Jobs gathered the iPhone leaders in Apple’s boardroom to talk about the state of iPhone development. Fred Vogelstein of Wired described the scene as a horror show of bad news.

“It was clear that the prototype was still a disaster. It wasn’t just buggy, it flat-out didn’t work. The phone dropped calls constantly, the battery stopped charging before it was full, data and applications routinely became corrupted and unusable. The list of problems seemed endless. At the end of the demo, Jobs fixed the dozen or so people in the room with a level stare and said, ‘We don’t have a product yet.’”

The fact Jobs seemed calm — instead of bringing his usual fire and brimstone—spooked everyone in the room. Vogelstein said one executive described the moment as “one of the few times at Apple when I got a chill.”

Because the iPhone announcement was going to be the main event at Macworld in a few weeks, any sort of postponement would have been disastrous. “For those working on the iPhone, the next three months would be the most stressful of their careers,” Vogelstein wrote. “Screaming matches broke out routinely in the hallways. Engineers, frazzled from all-night coding sessions, quit, only to rejoin days later after catching up on their sleep. A product manager slammed the door to her office so hard that the handle bent and locked her in; it took colleagues more than an hour and some well-placed whacks with an aluminum bat to free her.”

The problem was that everything was new and nothing worked. The touchscreen was new, so were the accelerometers. The proximity sensor, which turned off the screen when the user held the phone up to their face, developed a problem in a late prototype: It worked for most people, but it didn’t work if the user had long dark hair, which confused the sensor.

“We nearly shelved the iPhone because we thought there were fundamental problems that we can’t solve,” Jony told a business conference in London. “You have to detect all sorts of ear-shapes and chin shapes, skin color and hairdo … that was just one of many examples where we really thought, perhaps this isn’t going to work.”

But just weeks before Macworld, Jony’s team had a prototype that worked well enough to show AT&T. In December 2006, Jobs travelled to Las Vegas to show it to the wireless carrier’s CEO, Stan Sigman, who was “uncharacteristically effusive,” calling the iPhone “the best device I have ever seen.”

The arrival of the iPhone at Macworld was the culmination of more than two and half years of intense hardship, learning, and dedication to bring it to market. As one Apple executive summed it up, “Everything was a struggle. Every. Single. Thing was a struggle for the entire two-and-a-half years.”

When launch day came in mid-summer 2007, Jony joined the whole design team at the flagship Apple retail store in San Francisco. “We were excited,” said Stringer. “We had something new. There was an incredible buzz. … And there was an enormous crowd outside. We wanted to feel that enthusiasm and see people, see their eyes when they get these new products, the first people to get them. When the doors opened, there was mayhem. It was like a carnival.”

Stringer was overwhelmed with emotion. “We were obviously very, very proud. We’d worked really hard. It was—there was an enormous number of people that put in personal sacrifice and it was paying off in spades. It was a beautiful day.”

iPhone launch day: June 29, 2007

Photo: Jim Abeles

The iPod had been regarded by a lot of pundits as Apple getting lucky, a fluke, a one-off. When Apple entered the cutthroat cellphone market, it was predicted the iPhone would flop. Microsoft’s Steve Ballmer famously said it would never get any market share. But the iPhone was a hit from the start, and Apple used its old playbook of rapidly adding features and models.

Apple released the iPhone in mid-2007. By the end of the year, 3.7 million iPhones had been sold. By the first quarter of 2008, the sales volume of iPhones exceeded sales of Apple’s entire Mac line. And by the end of 2008, the company was selling three times as many iPhones per quarter as it was selling Macs. Revenue and profits were through the roof.

When Jobs unveiled the iPhone at Macworld in January 2007, he invited his old friend Alan Kay to the launch. Jobs and Kay knew each other from Xerox Parc, and later Kay had been appointed an Apple fellow, a kind of elder statesman, and worked for a decade inside Apple’s ATG group in the late ‘nineties. Kay is famous for prophesying the “Dynabook,” a tablet computer that would provide a window into all the world’s knowledge — back in 1968.

On iPhone launch day, Jobs turned to Kay and casually asked, “What do you think, Alan? Is it good enough to criticize?” The question was a reference to a comment made by Kay almost twenty-five years earlier, when he had deemed the original Macintosh “the first computer worth criticizing.” Kay considered Jobs’ question for a moment and then held up his Moleskine notebook. “Make the screen at least five-inches by eight-inches and you will rule the world,’ he said.”

The world would not have long to wait for the iPad.

Reprinted by permission of Portfolio/Penguin. Excerpted from Jony Ive: The Genius Behind Apple’s Greatest Products. Copyright 2013 Leander Kahney. All rights reserved.