My little red-haired niece approached the casket with a single flower and placed it with the father she looks so much like.

I raised my camera to my eye and made a picture.

Though secure with my reasons for snapping the photo, I understood how taboo this could seem to others. I never made a print to pass around or display. I look at the photo now, 10 years later, and get reacquainted with grief, struck by a visceral appreciation for a chapter that continues to unfold in my family story.

That picture was a fading memory until my recent trip to the Museum of Mourning Photography and Memorial Practice in Chicago, a collection of more than 2,000 postmortem photographs and funerary ephemera.

The curator is a young, energetic artist and entrepreneur named Anthony Vizzari. “I find a lot of beautiful things in these images,” said Vizzari, 34, whose first piece was a funeral card he found at a flea market when he was 16. “These are powerful, well-preserved documents that reminds us of our presence in the universe.”

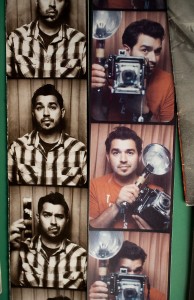

Vizzari’s museum, which he run out of A & A Studios, his business for building and restoring vintage photo booths, is open by appointment only and costs $100 to visit. This might seem steep but the price of admission comes with Vizzari’s personal narration through the collection, in a setting that chronicles the history of the camera about as well as any established photography museum.

Having a dead loved one photographed was an accepted practice in the late 1800s, as photography became affordable to the public. Rather than commission an artist to paint a portrait, families found it less expensive to memorialize their loved one with a photograph.

For many families, it might have been the only photo of that loved one, especially if the deceased was a child.

“I think for many people this was seen as a solemn and significant event in the life cycle to commemorate in much the same way as a christening or a wedding,” said Paul Frecker, a London-based collector of 19th-century photography. “It was also a chance to have one last portrait of a loved one. And perhaps there was also a desire to remember the death as a peaceful and beautiful event.”

Memorial photographs are highly collectible, fetching anywhere from a few dollars to hundreds of dollars depending on the rarity of the subject matter and type of photograph. Daguerreotypes command higher prices, Frecker said.

Funerary photography bookends a life

Vizzari’s collection of funerary photography is not for morbid fascination. He does not collect gruesome images and bristles at the occasional criticism that the collection is creepy or ghoulish. He is sincere in his efforts to preserve what he calls a vivid bookend in one’s life story. (See examples of the photos in his collection in the gallery above.)

The pictures of children in his collection give great pause. Some of the poses are angelic and peaceful, the children arranged to appear asleep or sitting upright surrounded by toys, flowers or family. In some, you see a mother stoically staring into the lens, holding her dead infant.

The bookend metaphor is especially evident in one piece Vizzari got from an estate sale. It is a mother’s journal that starts with a photo of a newborn daughter. Throughout the book is a photographic and written record of the girl’s growth for each year. The book ends with the 7-year-old’s funeral.

Other images in Vizzari’s collection show loved ones gathered around open coffins for what might have been a given clan’s only complete family photo. In one instance, a separate photo of a coffin was superimposed in a group photo obviously taken afterward.

Some photos, as Frecker suggests, mark the solemn occasion. Pictures of an open coffin surrounded by flowers and banners show the display of love and grief for the subject. Some elected to take these photos with the coffin closed or without the coffin.

Vizzari is skeptical of those who say funeral photographs are out of fashion. Photos that might have been taken in the late 20th century or even more recently still reside with families, he said. The time period in Vizzari’s collection starts around 1870 and ends with a few examples from the 21st century.

“(The collection) goes right up to the 1960s and then slows down,” he said. “It takes many years for these kinds of pictures to enter the market.”

He has spent more than half his life collecting mourning photos, going to flea markets, estate sales and searching online. The museum used to hang in his home, but his wife — though understanding and even involved in helping with his collection — grew tired of seeing the dead hang on their walls.

Vizzari’s own feelings for the collection are beginning to shift. He now has a young son and he is sometimes bothered when he looks at the photos of children.

He is thinking about selling off the pictures.

“You watch your kid grow up, laugh, play or be sad and you start to look at the pictures differently,” he said. “You don’t just see a dead child, you can see someone’s grief. It’s a bit much to take at times.”