Category: Book

Price: $16.59 hardcover

It’s a natural instinct to assume that a book written in the wake of a famous (and famously litigious) person’s death might well be a cash-in — particularly when the author of said book is an ex-lover, with an all-too-apparent axe to grind. That was my first instinct when approaching The Bite in the Apple: A Memoir of My Life with Steve Jobs, whose author, Chrisann Brennan, will be well-known to Apple followers as the first girlfriend of Jobs — and the mother of his daughter, Lisa Brennan-Jobs, who the Apple co-founder denied paternity of for many years. The suggestion that this is a money grab is seemingly backed up when Brennan starts the book by claiming that she not only never considered studying history, but had little interest in writing a book either: both seeming prerequisites for a person writing what essentially amounts to a modern history book. Misgivings deepen yet further when Brennan locates the book’s origins as following on from a 2006 spate of ill-health which left her financially destitute and “virtually homeless.”

This post contains affiliate links. Cult of Mac may earn a commission when you use our links to buy items.

“A wounded love letter…”

In some ways I was very wrong in this judgment of the book, which feels less like a cynical cash-in than it does a wounded love letter to a man the author never quite cracked the surface of. What follows zips unevenly between genuine insight, wild accusations, hormonal gushing (“God, he was cute”), and the kind of cod-philosophy it is easy to imagine a Palo Alto therapist prescribing alongside yoga and Greek yoghurt. (What, for instance, are we to make of the line: “I realized that Steve was entering the world stage through two bastions of male power from two hemispheres”?)

That isn’t to say that all of Brennan’s insights fall under this category, however. Some of her ruminations about Jobs are thoughtful and considered — and perhaps more importantly fill in some spaces in Jobs’ biography that would otherwise remain blank. We hear, for example, more than we ever have previously about Jobs’ relationship with his adoptive father, Paul Jobs (complete with speculation that Jobs may have been beaten as a child). Brennan traces Jobs’ seeking of approval from older male figures in his life — a situation which played out most notably with later Apple CEO John Sculley — to his relationship with his militaristic father, and even links this to Jobs’ decision to adopt a uniform in later life (the famous blue Levis, black turtleneck combination) when he reached “elder” status himself.

We also hear far more details about Jobs’ relationship with another surrogate father figure — his Sōtō Zen teacher Kobun Chino — who Brennan paints as one of the most influential figures in Jobs’ life, but who received a mere thirteen mentions in Walter Isaacson’s acclaimed Steve Jobs biography (thanks e-reader search!).

Undoubtedly Steve could be mercurial; turning on a dime from effusively praising a person to viciously condemning them, and both sides of that personality are on display in The Bite in the Apple. Brennan recalls Jobs’ goofy sense of humor as a teenager, seen through his retro robot impressions. She describes his alter-ego of “Oaf Tolbar” (“He signed love letters with ‘Love, Oaf,’ she writes), and even drops a line about his supposed love of auditing Reed College dance classes (“I tried to imagine him in a leotard, but I couldn’t quite see it.”) She also reveals Jobs’ “strong sense of having had a past life” as a World War II pilot, and details his post-India forays into tantric sex — with an anecdote about Jobs trying to coerce Brennan into making “tantric love with him in his garden shed”, which momentarily threatens to tip the book into Fifty Shades of Steve territory.

“[H]is coworkers found him so dark and negative”

At other times, Bad Steve comes out. Brennan disagrees with the oft-cited story about Jobs being moved to the night shift at Atari because he smelled bad — explaining the decision by instead saying that “his coworkers found him so dark and negative.”

No event paints Jobs in a worse light, however, than his abandonment of daughter Lisa. If there is a heart to the book after a meandering, slow-going fast half, it is the story of how Brennan wound up getting pregnant, having a daughter, and struggling to have Jobs acknowledge his role as the father. Brennan notes that Jobs didn’t phone or turn up at the hospital until three days after his daughter’s birth, and later (in)famously claimed that “28% of the United States could be the father” of his child, before a DNA test eventually confirmed paternity.

There is certainly a cruel irony to Jobs denying paternity of his then-only child, shortly before Time magazine (at least according to some versions of the story) was due to name him “Man of the Year”. In a further twist, Time wound up changing the award to “Machine of the Year” — offering a poignant analog to Jobs’ emotionless, machine-like behavior. There is additionally a disturbing anecdote about Jobs behaving inappropriately around his daughter, which causes Brennan to interject the disclaimer, “I will be clear … Steve was not a sexual predator of children.” I wasn’t sure what to make of this, and for the first time made me worry that my initial misgivings regarding the book were correct.

The real appeal of a book about young Steve Jobs, of course, is that we get to see some of the embryonic jigsaw pieces that would later assemble themselves to create one of the most successful entrepreneurs of the last century. “Steve was a problem solver,” Brennan writes. “He would often explain a problem and then show me the way through it.” Brennan here refers to dietary suggestions, or else the “decoding” of Bob Dylan lyrics, but one can easily extrapolate and see this as the basis for Jobs’ later business success: not only helping create striking new products, but telling us how they would improve our lives. We learn that Jobs had a top-of-the-range bright red IBM Selectric typewriter growing up: evidencing a love of high quality, and beautifully designed, technology even from a young age.

Other times the reader feels that they are perhaps overstretching to read revelatory details where none might exist. Does Brennan’s suggestion that “Steve lived in a symbolic world of his own” somehow prefigure his insistence on characterful icons (symbols by any other name) on the Macintosh? Or does it just mean that Steve was a bit detached growing up?

There are a few pieces of Apple trivia contained within The Bite in the Apple that I don’t believe have popped up anywhere else. Brennan reports, for instance, that Jobs originally wanted his daughter to be named Claire so that Jobs could name his next computer The Claire, as a nod to the “clairvoyance” of Apple’s ability to look into the future.

The good thing about learning previously unreleased bits of information, of course, is that it helps us fill in the gaps about Apple history. The bad part is that when you’re dealing with such a well-documented part of Apple history, going along with a story that has been reported by no-one else makes you question other details of the book. (Since Jobs denied for years that the Lisa computer was named after his daughter, why did he need his daughter to be called Claire to name his computer this?)

“Helps us fill in [some] gaps [regarding] Apple history”

Whether or not this book will appeal to you rests finally on how interested you are in Jobs’ personal life during the 1970s and 80s. If you felt like you learned everything you needed to know about Jobs from the 2011 Isaacson biography, The Bite in the Apple will be unlikely to come with a recommendation. The same is true if you’re looking for a business book, or anything that touches on Apple as it exists today.

Personally, I found parts of the book that interested me as an Apple fan (and former Jobs biographer), and other parts which felt superfluous, or overly unqualified. Ultimately this book won’t unpick the complex enigma that was Steve Jobs, but it may provide you with one or two insights that will augment the other information that is already out there.

Brennan’s relationship with Jobs was challenging up until the end, when she was un-invited to his Stanford memorial service after agreeing to cooperate with a story for Rolling Stone magazine. The Bite in the Apple is presented as closure for Brennan on the subject of her one-time lover, but in some senses it still feels like she hasn’t made her mind up.

She may well describe Jobs as a “haunted house” who disdainfully treated people like rats in a feedback experiment, but yet she clearly still feels strongly enough to write a book — during which she defends him from criticism at various points.

And yes, she acknowledges, she did write it on a Mac.

P Product Name: The Bite In The Apple: A Memoir of My Life With Steve Jobs The Good: A different take on the personal life of Apple’s co-founder The Bad: Uncomfortable reading in places. Will not appeal to everyone. The Verdict An interesting, if uneven, book for Steve Jobs completists Buy from: Amazon.com |

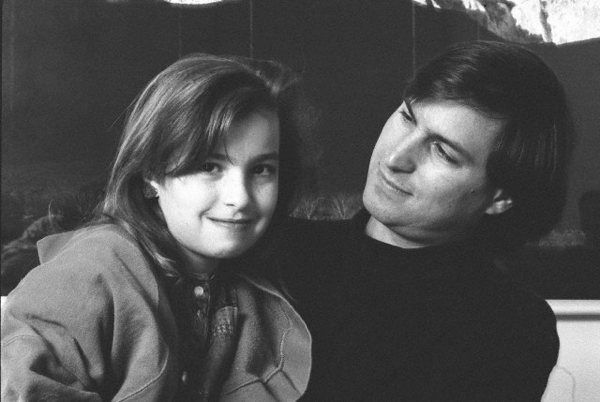

![The Bite In The Apple: A Memoir Of My Life With Steve Jobs [Review] youngstevejobs](https://www.cultofmac.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/youngstevejobs.jpg)