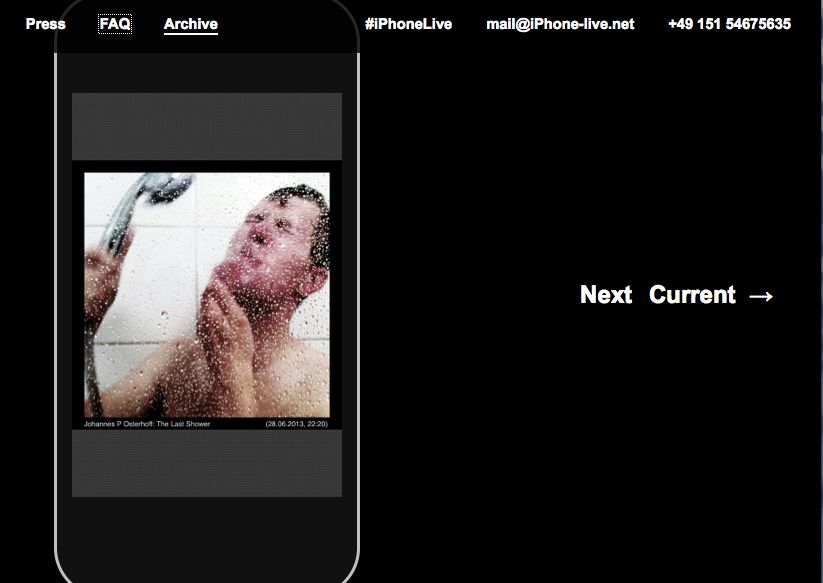

For a whole year, Johannes P. Osterhoff broadcast what came across his iPhone screen to an open internet page.

Anyone who stumbled onto his iPhone Live website could spy on how much beer he was drinking, who called him, what games he was playing, his email inbox, how long his showers took, see what gigs he had lined up, his Twitter exchanges and what his moods were. As you can imagine, there were some interesting consequences for his friends and a few worried conversations with his mom.

Osterhoff is something of a techno-provocateur. Based in Berlin, he has pwned Apple ads with porn in a subway station, built himself a wearable OSX home and aimed high with a William Tell iPhone project.

Calling himself an interface artist, this project was less playful than some of his previous efforts. It grew from being “concerned about the growing amount of personal data that was stored on smartphones and that users lose control over it,” he told Cult of Mac.

With the stranger-than-science fiction story of the National Security Agency coming to light at the tail end of his iPhone Live year, the experiment has added resonance. While Americans disapprove of surveillance programs – about 53% were against spying in a Gallup poll taken after the Edward Snowden story broke – our participation in social media and the traces we leave publicly has skyrocketed. In 2008, just 12 million of us were “heavy” social media users – now that figure is 71 million, or about six times as many people, according to Edison research. That’s a lot of status updates.

The Peek-A-Boo Challenge

In a way, Osterhoff is simply going bigger with what we all do, every day. You may laugh at lifecasters, but that’s what you do with every tweet, Facebook update, FourSquare check-in and Flickr snap. We don’t do it for money, though — and maybe we should stop sneering at those who do. At least they get paid for it. We do it to stay in touch. To prove we matter.

Osterhoff’s unease – and impetus – for the project came with the realization that “interaction with our smartphones serves the companies who provide platforms and apps more than it serves us, the actual users and the originators of information and data.” He wanted to share his information but keep control over what he was providing. This proved his biggest challenge.

When the project captured media attention, there were a flurry of visitors peering into his daily life on the web. Osterhoff tried to shield his friends and acquaintances from making unwanted cameos. He rigged up his jailbroken phone so that every time he hit the “home” button it would take a screen shot and upload it online. This gave him the flexibility to avoid capturing anything that might be better left private.

“Luckily apps provided me with more freedom than I had expected,” he said. “If I did not want to show the content of an email for example, I usually navigated back and showed the folder structure of my inbox instead. On the other hand, I wanted to entertain my visitors, so I used Camera+, Instagram, Google Maps more frequently to tell stories about my life. I would not have done this without an audience.”

When Your Peeps Want More Privacy

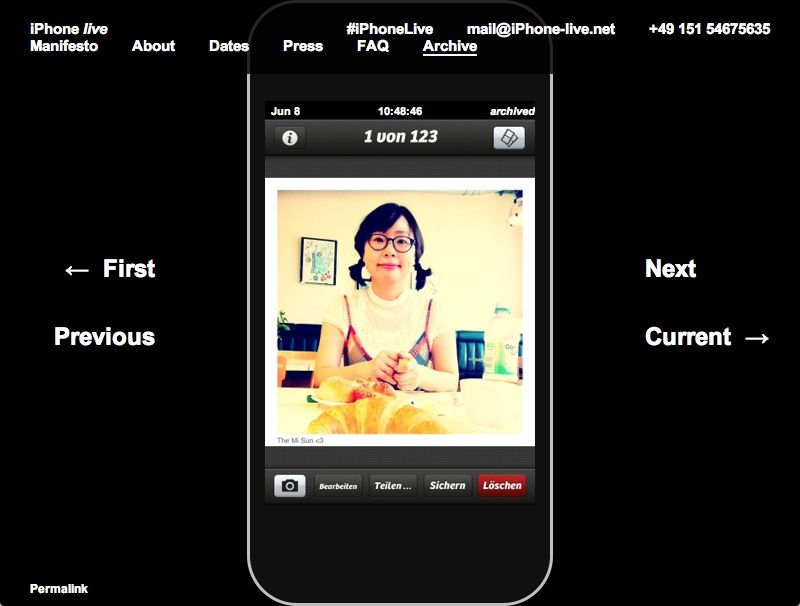

Osterhoff’s wife, Mi Sun, gladly participated in the project. The pair even enjoyed documenting their trip to Korea, “staging” the more interesting and photogenic parts of the journey to keep friends and family in the loop, he said. His mom, who voiced concern initially about the project, checked up on him after she thought he’d logged too many beers the night before — but she did like being able to stay abreast of his everyday doings any time she wanted. For his friends, it was different.

“I received less text messages then I did before the performance,” Osterhoff remarked. “My friends preferred to call me directly. The topic then would not be tracked and the call would only be listed in the call history.”

Life After the Truman Show

He logged in 13.575 screenshots of his home screen during the project, where anyone could participate by using his phone number at the top of the site or sending him an email. Osterhoff took the performance live, too, participating in events like Berlin’s Transmediale Festival where his iPhone screen was projected behind him as people live tweeted or emailed him comments and questions.

The apps taking up most of the limelight were Instagram, Mail, Phone and Safari, with a few guest spots from players like Pizza.de, Shazam, Cut The Rope, Angry Birds and Ikea. After an initial burst of energy, Osterhoff’s postings fell off about two-thirds of the way through the show. A broken dock connector (lint turned out to be the culprit) meant he had to cool his heels and wait for a replacement part to finish the experiment.

So, what happens after you’ve bared all for a year?

“Currently, using my iPhone feels pretty boring,” Osterhoff told us a few weeks after the end of the experiment. “I realized that I did a lot of stuff only due to the performance — tracking my showers, beers and mood for example. I have already stopped doing that, since it is pointless without an audience.” He’s back to heavy usage of the basics, namely: calls, Mobile Safari and Google Maps.

Osterhoff hasn’t walked out on lifecasting altogether, though. His latest project, called “Dear Jeff Bezos,” also centers around privacy by documenting what he’s reading on an Amazon Kindle. He jailbroke the device so that it every time he sets a bookmark, it sends an email to the Amazon CEO.

“Not so long ago it was very simple to read a book in private, Osterhoff said. “Companies like Amazon are interested in exclusive ownership of data, because with this exclusivity comes value. As a user of such services, one loses not only control but also authorship of the data one generated. To make the data I generate public is to devalue it. This is why I prefer to share data in an open format.”

The iPhone Live project also exposed his own ignorance – when a friend asked him over Twitter about spy operation PRISM, Osterhoff mistakenly replied on screen about the puzzle game of the same name. Perhaps too engrossed in tracking his own doings – using apps like iBeer, Mr.Mood and ShowerTimer – he hadn’t paid that much attention to the news.

Still, broadcasting our own data may be the way to go. “Screenshots contain a lot of information for humans, but it is still difficult to extract machine-readable data from them,” he said. “So actually, iPhone live also shows how we could share information with friends only and make it difficult for others, such as the NSA, to extract meaningful data.”