Category: Cameras

Works With: Uh, hands?

Price: $1,200

First, remember one thing: this isn’t a full review of the Fujifilm X100S, even though I had to write it up there in the title to please our CMS. I’ve only had the thing for a few days, and even though Cult of Mac isn’t DP Review, a few days isn’t enough to evaluate an iPhone case, let alone a camera like the X100S.

On the other hand, the X100S is So Hot Right Now, and I’ve been staying up tip 3AM since I got it because I can’t stop playing with the thing. Combining those two interesting facts leads me to think that an in-depth first look might be a good idea — especially as you can now convert the RAW files on your Mac using the just-released Lightroom 4.4.

Let’s take a look — You might want to go make a cup of coffee first.

Overview

The X100S is a rangefinder-style camera. That is, it works a lot like the Leica M-series for example. These cameras have a lens for taking the picture, and a separate viewfinder with its own lens in front. Clever mechanical linkages and optics match the lens’ focus to a square in the middle of the viewfinder, and when you line up the actual image and the image superimposed on this square, it’s in focus.

While the X100S doesn’t use rangefinder focussing, it does have a big, bright optical viewfinder. It also incorporates an electronic viewfinder, and has an LCD on the back, and you can use any of these to snap your pictures.

if you just want a camera that handles as well as any film camera you ever owned, then yes. Go buy it. You’ll love it,

Inside is a 16MP X-Trans sensor, which is APS-C-sized, the same as you’ll find in most SLRs, and on the front is a 23mm (35mm equivalent) fixed lens.

Other standout features are the proliferation of knobs and dials for the main controls, truly usable manual focus (the first I’ve seen in a digital camera — including high-end SLRs) and that amazing styling which simultaneously looks eye-catchingly cool and yet remains discreet enough to let you stalk the streets and snap away without freaking anyone out. And did I mention it is all but silent?

Hardware

Lens

The X100S has the same 35mm (equivalent) lens as the older X100. It has a maximum aperture of ƒ2, and inside is a leaf shutter. A leaf shutter is just like the aperture diaphragm, and is also found in cameras like the Hasselblads that were taken to the moon. Regular focal-plane shutters sit over the sensor and have two curtains. Imagine that you have the drapes over your window pushed to one side, one fully covering the window, the other bunched up at the side. To “expose” the room, you open one curtain, then pull the other across to close the gap. Now the bunched up curtain is on the other side of the window.

With faster shutter speeds, the second curtain starts to close before the first has reached the other side. This effectively gives you a traveling slit of light which moves across the sensor. This is fine, unless you use a flash. A flash fires all its light in an instant far shorter than a typical shutter is open, and so it illuminates only the part of the slit that is open when it flashes.

A leaf shutter, on the other hand, opens all the way at every shutter speed, opening up like a metal sphincter and then snapping shut again. This lets you use flash at any speed, not just the maximum sync speed (typically 1/125th sec) of regular cameras.

It is also almost silent. In fact, if you switch off all the beeps and fake shutter sounds, you can take close-up portraits and your subject won’t realize you’ve taken a shot. It’s that quiet.

Viewfinder

The X100S’ big, bright optical finder shares some rangefinder features. It’s bigger than the actual image you’ll take, which means there’s a border around the edge of the picture, letting you see what’s about to come into frame. For many, this is reason enough to buy the camera.

But it also has one killer feature never seen before Fujifilm’s X-series cameras: A hybrid viewfinder. This clever contraption consists of a straight-up optical ‘finder (OVF), bigger and clearer than many SLR viewfinder, plus an EVF (electronic viewfinder) off to one side. A prism arrangement projects the LCD viewfinder’s image in from the side, letting you switch between views.

Hybrid Viewfinder — Electronic and Optical Together

What’s more, the 2.35M dot EVF can even project info onto the optical finder. This means you can see histograms, exposure info and more overlaid on your optical image. It is, frankly, amazing. There’s even a moving “brightline” rectangle which shows you just which part of the scene you’ll actually capture. This changes to show the aspect ratio, too, for shooting Instagrammatical squares or long HD video (the OVF is especially good for video as you can see exactly where the mic boom is and avoid ever getting it in frame).

Flip the little leer on the front of the body (it looks like the self-timer lever on film cameras) and you switch to the EVF. This has the advantage of filling the screen with the image you’ll take, and of showing you exactly what you’re shooting. Lag is minimal, and the resolution is high enough that you don’t feel like you’re looking at a TV screen. You can also zoom in on a point to help focus.

Which brings me to the hybrid finder’s neatest tricks. You can use the superior (I think it’s superior, anyway) OVF and flip to the EVF as needed. And this happens automatically. For instance, pressing on the little wheel at the top right of the camera’s backplate will quickly switch to the EVF and zoom in to the current focus point. From there you can manually focus whilst zoomed in, making it easy to get a quick lock.

Or you can choose to have the camera flash up the picture you just took for a half second (or more), letting you check everything is ok. Then you’re dropped right back into the optical finder to keep shooting.

One final note on that optical viewfinder. It’s even better than using the optical finder in an SLR, because it never blacks out. With and SLR, the mirror flips up and blacks out your view at the precise moment the picture is taken. With a rangefinder, you can see the moment itself, and often this is enough to let you know that you got the shot and can move on. With an SLRm you can let loose and spray the scene with shots like a machine gun, and still come up empty.

Let me give you an example. The Lady is notoriously hard to photograph (and not just because she complains about ll the pictures when she seems them). She’s a blinker, and in around 80% of pictures I or anyone else takes she has her eyes closed.

Shooting her over the last few days using the X100S, I have gotten only a couple of blinkers from her. This is mostly down to the intimacy of the rangefinder view, which lets you really look at your subject and their surroundings. This might sound wishy-washy, but it really makes a huge difference. There’s a reason photojournalists portrait-shooters use Leicas.

Manual Focus. Better Than Auto?

Speaking of manual focus, the X100S does a great job. The older X100 was rather crap at it, as you had to spin the focusing on the lens around like a million times to get from closeup to infinity. The X100S feels like a film camera, with a nice weight to the ring, and a good “pitch” (the amount of turn needed to do the actual focussing). It also has one advantage never seen with a true manual lens: you can reverse the direction you turn the lens to focus in and out, making it match either your Nikon or Canon’s direction. Very cool.

There are also some software aids to manual focus, both new, and both using the new sensor’s on-chip phase-detection AF. Essentially, the sensor can now tell exactly how far out of focus it is. This makes for less hunting around when auto focussing, but has a side-effect that can be used to make an old-school split-image focus aid in the middle of the screen. You just move the lens until the split sections line up and you’re good.

The other manual focus aid is Focus Peaking, which puts a white outline around anything that’s in focus. It’s been used in movie cameras for years, and is now finding its way into high-end SLRs. And of course into the X100S

Buttons/knobs

If you came to photography from all-manual film SLRs, then you probably have a soft spot for manual controls. And you’ll love the X100s’ controls. The aperture is controlled with a ring around the lens. The top plate contains a shutter-speed dial and an exposure-compensation dial. The viewfinder switch is a lever on the front, and the focus-mode switch is a clunky slider on the left edge of the body.

This might sound retro, but it means that you can adjust everything without taking the camera from your eye. You can even set the thing in full manual and it just gets out of the way. Let me put it like this: The X100 will never come between you and your photo. Instead of having to search through menus, you just twist a knob, almost subconsciously, and take the shot.

The control dial feels cheap, and the on/off switch (a twisting collar around the shutter release) is far too easy to switch on by mistake.

Not all the knobs are equal, though. The shutter release is ridiculously positive: you’ll never take an accidental shot, nor will you miss one. The shutter and exposure compensation Knobs are also improved over the X100 (apparently — I never used that camera) and are nice and stiff.

But the control dial feels cheap (although not flimsy), and the on/off switch (a twisting collar around the shutter release) is far too easy to switch on by mistake. I got around this by buying a couple of spare batteries and letting the auto power off do its thing.

And you should buy some extra batteries, as the X100 eats them. I have no idea of real-world use yet as I’m still burning power as I play with all the settings, but the batteries are so tiny I’m surprised they work at all. They’re also small enough and cheap enough that you can keep a few in your bag at all times.

Fear not, though: the money you spend on batteries will be saved on a remote control. That’s right: the X100S has a threaded hole in the top of its shutter button. This lets you use cheap old manual cable releases. If you can still find one I guess.

Speed

Shooting

The camera is fast. I’ve heard that the X100 was sluggish at everything, from menu navigation to focussing. The S on the X100S might stand for “speed,” then. The new phase-detection AF is as quick as a DSLR (except in the dark, where it can hunt around a bit before giving up), and if you use a fast SD card you’ll likely never have to worry about the camera slowing down on you.

The viewfinder switching is also fast, and even RAW processing in camera is quick. Like, iPhone 5-quick. I’m notoriously fussy about slow cameras, but this one feels as fast as an all-mechanical film camera. Which is as fast as you can get.

Handling

Menus are snappy, knobs and buttons all fall to hand (no small feat, as I have big hands an the X100S is pretty small. There’s not much more to say yet — I’ve only been using it for a few days after all — but so far it’s easily the best digital camera I’ve ever used.

I’ve only been using it for a few days, but so far it’s easily the best digital camera I’ve ever used.

One other note on handling. Fujifilm has added a neat Q button, which gets you to a quick menu for adjusting oft-used settings. One accessed (you’ll see it on the LCD screen), you can navigate the grid with the “cursor” keys around the control dial, and then change the settings of the currently-highlighted item by spinning the dial. It’s very fast and easy, and gets even quicker as you use it more, thanks to the fact that the settings never move.

Images

The images from the X100S are outstanding. The X-Trans sensor has its red, green and blue pixels laid out in a non-standard, non-regular pattern. The idea is that it won’t suffer from moiré problems when confronted with a regular pattern. You know when you’re watching a TV news show and they talk to some guy with a loud tie, and that tie’s pattern seems to shimmer and pulse? That’s moiré, caused by interference between the pattern on the tie and the pattern of the pixels.

The usual fix is to put an “anti-aliasing” filter in front of the sensor, which essentially blurs the fine details of the image to avoid this interference. The X-Trans instead shifts its pixels to a non-interfering pattern, and ditches the filter. The result is sharper images and more detail.

In practice, the images really are sharp and clear, and very filmic to my eye. They’re also impressively noise free. You can crank the sensor to ISO 1,600 without worrying, and even ISO 3,200 — a speed at which film grain grows to the size of footballs — is clean. I haven’t gone higher than this yet, but I have a feeling that ISO 25,600 in B&W is going to look pretty cool.

RAW

Right now, RAW processing of the X100S’ X-Trans sensor is pretty crappy. Or so they tell me. You could use Fujfilm’s own app, but that’s just torturing yourself for no good reason. Or you could use Lightroom, which — in its new 4.4 incarnation — does a great job. Some folks tell me that the RAW conversion is bad even in the newest Lightroom, giving weird “watercolor” effects to foliage when you view the pixels at 100%.

For me the gorgeous quality of the X100S’ photos is hard to fault.

To which I say, so what? If you like to look at 1:1 on-screen enlargements of leaves and grass, then you might disagree, but for me the gorgeous quality of the X100S’ photos when viewed at normal sizes is hard to fault. Plus, the RAW converting will be sorted out as soon as Adobe manages to convince the boffins at Fujfilm to give them the secrets to the X-Trans sensor’s sauce.

I will say that the RAW files are clean. The pictures look both sharp and rich, and you can get away with a lot of pixel pushing in Lightroom without breaking anything. Not that you’ll need that much processing. I usually dick around with my RAW photos quite a lot, but with the files out of the X100S, I find I don’t really need to do very much at all.

In fact, the straight-out-of-camera (SOOC) JPGs are so good, you might not even need RAW for at all

JPG

I know, the RAW files are the digital negatives from your camera, and they’re sacred. I’m not saying that you shouldn’t keep shooting RAW, especially with storage as cheap and plentiful as it is these days. Just that you might want to treat the files like you treated your negatives: throw them in a drawer and forget about them until you need them.

Because, you see, the JPGs from the X100S are that good.

Fujifilm’s film heritage shows when it comes to the JPGs. The straight up conversion gives Fuji’s typical strong greens and blues, and you can also choose from a small range of film emulations, which give equally filmic results. You can also tweak various aspects of the conversion from the Q-Menu, like the film emulation type, highlight and shadow tones, color strength and sharpness. And you can also switch to B&W, including a few settings which simulate the use of colored filters in front of the lens (note, these don’t add color to the picture). Sadly, Fujifilm didn’t Add in any emulation for its excellent black and white films.

I like to shoot B&W, and from what I gather on the internet, when the camera converts its pictures to B&W JPGs it uses the RAW color data to inform the conversion. What I’m certain of is that the pictures aren’t just desaturated color photos. They have a character which is as distinguishable as any film, but all its own. Plus, you can tweak the output to something you like.

The very best thing about shooting B&W with a RAW-capable camera, though, is that you get to have your cake and eat it. I can shoot RAW+JPG, and the camera saves the RAW negative along with a B&W JPG file. If you set Lightroom not to ignore these JPGs (in the General settings pane, check the “Treat JPG files next to raw files as separate photos” box) then you get to keep both. If you like, you could even spend the time to emulate the camera’s conversion in Lightroom. I won’t be bothering with that — the camera already does a fantastic job, and I’d only go and save my own results out as JPGs anyway.

In-Camera Processing

But there’s more. The camera can process its own RAW images, creating JPGs that are ready to share with the world. This is good if you shoot only RAW but need to give a copy of one of your pictures to someone whose device can’t handle a RAW file, or if they have an iPhone and prefer a small JPG to a giant RAW file.

In-camera JPG conversion really shows off Fujfilm’s film heritage.

But it’s also good for making some really gritty shots right there, using Fujifilm’s great conversion software. The only downside is that you can’t save your settings for re-use — you’ll have to (literally) dial them in every time.

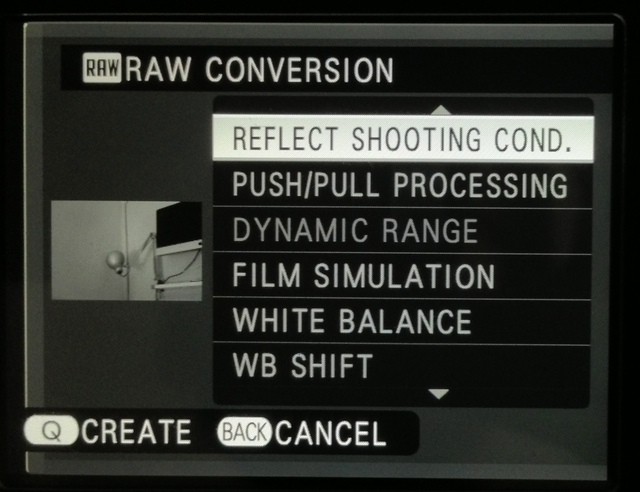

To access the RAW Conversion feature, you can either go through all the menus trying to find it, or you can just call up the image on the playback screen and hit the Q button. This takes you right to the editor. Here you can adjust exposure (remember, this is the same kind of thing you can do with desktop software, so this is also a good way to save a badly-exposed shot), dynamic range, add a film simulation, tweak white balance and sharpness, change the highlight and shadow tones (from hard to soft) and choose a color space for the final file (SRGB or Adobe RGB). Hit convert to see the result, and then save that result to your SD card if you like it.

Like I said — it’s a shame you can’t save your tweaks as a preset to apply to all your pictures, but maybe a future firmware update will add that feature.

Tips & Tricks

In the few days I have been using the X100S, I have also spent far too long reading about it and its predecessor in forums. Between these two, I have found a few neat little tip that’ll help you get even more out of this amazing little camera.

Focus Zoom in Manual

You can choose a setting to switch the viewfinder to the EVF every time you twist the focus dial, offering you a zoomed-in view of the focus point, complete with your choice of split-image or focus peaking. This gets annoying fast, so switch it off and press the center of the little command switch (top right of the back of the camera, up on the silver part). This does the same thing, but only when you want it to.

Manual Auto Focus

If you set the focus mode to manual, you can then use the AEL/AFL under your right thumb to activate the autofocus. This lets you focus manually, but when to quickly zip the image into focus automatically should you need to. It also de-couples focussing from the shutter button, which lets you focus and shoot independently.

Note: the focus-point indicator in the optical viewfinder disappears in manual mode, so you’ll have to rely on the camera to take care of it for you (it focusses on whatever is in the center of the frame, as far as I can tell). If you’re still not sure, a quick flick of the viewfinder-switching lever will let you check the EVF.

An additional bonus of using this method is that you don’t have to engage the separate macro mode to focus close up, which you’re forced to do in some other modes (I still haven’t worked out the rules for that one yet).

Focus Point indicator in Playback

Remember the command switch you pressed in the first tip above? In playback mode (when zoomed fully out on the image) push that switch to the left and a little green cross will appear on the screen to show you where the camera was looking when it focussed. Handy for learning how the camera thinks, among other things.

My setup

For those that care, here’s a quick summary of my own setup, as tuned over the last few days.

I shoot in aperture priority, with the focus set to manual, and using the trick above to autofocus the camera. This is similar to the setting I used on an old Nikon D700 and an even older F100. I like that the focus only activates when I want it to, and not every time I half-press the shutter.

I use the optical viewfinder (OVF) almost exclusively, in the simpler Standard view (the Custom view adds all sorts of extras like a histogram and an on-screen level), switching to the EVF for a little help when I focus manually. I have all auto-review settings switched off — while I like that the camera can quickly show me the picture I just shot, right there in the viewfinder, I prefer to see what’s happening in from of me. Just because I grabbed a shot doesn’t mean a better one won’t appear right after.

I also use the camera in silent mode, which switches off not only the beeps and shutter sounds, but also extinguishes the AF assist lamp, which is a dead giveaway that you’re taking pictures. I’d rather switch to manual focus in low light, or just guess (the in-finder distance scale helps you to guesstimate focus distance).

One note: When you take a picture, the brightline frame in the OVF blinks off momentarily, so you will know it happened even in silent mode. If you’re in a very quiet place you can hear the actual shutter move, but it is so quiet it makes Leica’s legendarily silent cloth shutters of old sound like you kicked over a trashcan whilst trying to sneak into the house drunk late one night.

I also use auto ISO. You can tell the camera what ISO you want to use most of the time, plus a maximum ISO that it’ll gradually crank up to as the light gets low. Then you set a minimum shutter speed. I have set ISO 200 and ISO 1,600 as my limits, and 1/60th sec as my trigger. That it, the camera will stay at ISO 200 until the light drops low enough to force a shutter speed of 1/60th sec. Then, and only then, it’ll start cranking up the ISO to keep things from getting shaky.

It works pretty well, although I have been spoiled by the excellent auto-ISO on the Lumix GF-1, which also took into account how much the camera was shaking.

The LCD stays off until I want to play back a picture — I find I like to use the camera almost like a film camera, without looking at every photo as soon as I take it. It also helps to save power.

Speaking of power, I don’t bother with any of the power-saving settings, as they all sap performance. OVF power saving apparently slows down autofocus. Using quick start uses more power, but who cares? (Spare batteries, remember?) You can also choose to have a detector switch automatically between the LCD screen and the viewfinder, but I don’t use the screen much whiles shooting (and hitting the Q button lights it up anyway).

Hardware-wise, right now I have a UV filter over the lens, which fits nicely under the super-cool metal (magnesium, I think) lens cap, and I carry a lens-hood for bright light (which is most of the light here in Barcelona). The hood does block out the lower-right corner of the OVF, but I can live with it. I’m also using the supplied strap (too short for my tastes) and no case: I have a clean pocket in my Rickshaw bag padded with a pair of wool socks.

The one big problem

The only really bad problem I’ve encountered so far is that the camera really, really hates to snap a picture with the lens cap on (yes, laugh it up, but it’s easy to leave the cap on when you use a rangefinder). If I hit the shutter too hard when I wake it from sleep, the camera takes a shot and the orange LED on the back starts to go crazy, switching on and staying on. Nothing seems to help except pulling the battery — even cycling the power switch has no effect. I’m looking in to this.

The Verdict

The Fujifilm X100S Costs $1,200 (I got it for way less by trading in a bunch of old Nikon lenses and an SB900 flash), and is worth every penny. It’s the first digital cameras I have used that comes close to being as good as my old Leica M6. No, it’s not a Leica, and it doesn’t have the look that comes from Leica’s amazing lenses. Then again, the M9 costs ¢9,000, plus a few grand more for a lens.

What the X100S is is a serious camera for photographers who like to take pictures. That might sound trite, but once you’re done setting this thing up (and you can customize it like a tailor can customize a suit), it disappears in your hand. Back when I shot film on a Leica, I never felt I was being slowed down by the manual exposure and focus. It was as fast and easy as auto is today (more or less, anyway). Quite the opposite in fact: the M6 helped me to get pictures I never could have gotten with an SLR, by being smaller, faster, quieter and — most of all — by not having a viewfinder that never shows you the moment you’re actually capturing.

To call the X100S a “Leica-Lite” is unfair. What Fujifilm’s designers have done is start with the same concepts as Leica’s M-series designers (all long-dead now, seeing as Leica hasn’t had a new idea in a century) — a shutter dial, an aperture ring, a small body and prime lens and a big, oversized optical viewfinder — and built a modern camera with them.

While Leica is off making cameras for collectors that’ll never ever shoot a frame (and at the same time still — almost paradoxically — making some of the best lenses on the planet), Fujifilm has nipped in and eaten its lunch.

The hybrid finder, the X-Trans sensor, the all-manual controls, the metal body, even the proper strap lugs and threaded cable-release socket all show that the X100S has taken the best of camera design from history, and put it all together using the best of modern technology.

There’s even a hint of Apple-like compromise in here, leaving out many features so the remaining ones can be better: The non-changeable lens is the most obvious of these, banking on the fact that most Leica-shooter never used anything but a 35mm Summicron anyway and using that knowledge to keep the camera small and light.

Should you buy it? You probably know the answer already. If you want a rangefinder-style camera, or if you just want a camera that handles as well as any film camera you ever owned, then yes. Go buy it. You’ll love it, and you’ll actually want to take more pictures because of it.

If you’re worried that you might need a zoom, or wonder why on Earth you’d ever need an optical ‘finder when you have an electronic one, or you think that 1,200 bucks is way to much for a camera with only one focal length, then no. This might not be for you. And that’s cool, because if Fujifilm had tweaked the camera to appeal to a wider audience, then it would never have made the perfect camera for me.

Product Name: : X100SThe Good: Amazingly well-built, full-manual controls, fast, gets out of the way, looks great… Everything else. The Bad: Dodgy RAW conversion support from third-parties, goes crazy when you snap a picture with the lens cap on, no Leica logo on the front (kidding!) The Verdict If you want it, buy it. It’ll live unto your expectations Buy from: Fujifilm |

![Fujifilm X100 Is The Best (Digital) Camera I Have Ever Used [Review] IMG_6042.JPG](https://www.cultofmac.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/IMG_6042.jpg)